ARCHBALD — The Project Gravity data center campus slated for Archbald could pump in hundreds of thousands of gallons of water daily from Lake Scranton for cooling.

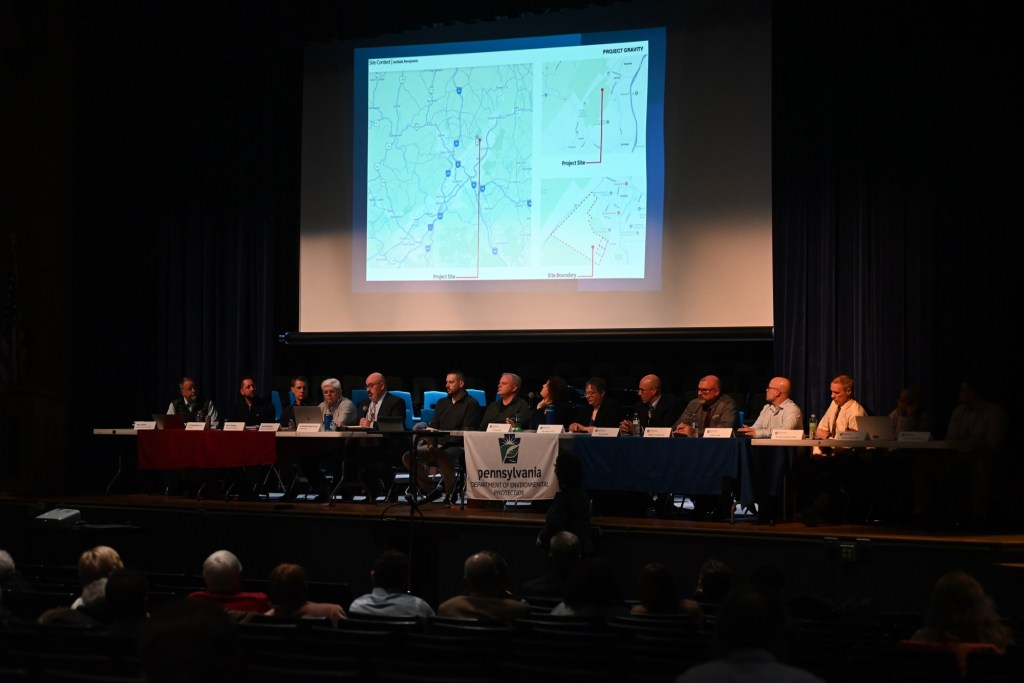

Representatives from Archbald 25 Developer LLC gave a brief presentation Tuesday evening to a crowd of about 150 inside the Valley View High School auditorium on their plans to build seven data center buildings across 180-plus acres along Eynon Jermyn Road and Business Route 6. A question-and-answer session followed the presentation, where close to 20 speakers, including a state representative, inquired about the project and the ongoing regulatory process that could allow it.

The state Department of Environmental Protection organized the two-hour public information session as it considers applications from the data center developer for a water obstruction and encroachment joint permit to allow it to fill in wetlands and waterways, as well as a general National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit, or NPDES permit, to allow for earthmoving on the site. Developing the data center campus will permanently impact 2.24 acres of wetlands and 459 linear feet of isolated stream channels.

To answer questions about the regulatory process, the DEP had its own panel from its Northeast Regional Office, including the department’s waterways and wetlands program, clean water program, safe drinking water program, storage tanks, and air quality program. State Rep. Kyle Mullins, D-112, Blakely, and state Sen. Rosemary Brown, R-40, Middle Smithfield Twp., both attended the meeting, with Mullins also speaking.

Project Gravity became one of the first data centers proposed in Lackawanna County when developers submitted plans to the borough on April 2. Nine months later, Lackawanna County has at least 10 proposed data centers and campuses, with five in Archbald, two in Jessup, and other proposals in Dickson City, Covington and Clifton townships, and Ransom Twp.

Of those proposals, Project Gravity is the first to have a DEP-organized meeting. DEP regional communications manager Patti Monahan moderated the session.

About Project Gravity

Scranton attorney Raymond Rinaldi represented Archbald 25 Developer, joined by a panel of representatives from engineering firms Hershey-based ARM Group LLC and Kimley-Horn, a national company with an office in Harrisburg. Although no one from the data center developer itself took the stage, Archbald 25 Developer is a limited liability company linked to national data center developer Western Hospitality Partners, initially filing with the Pennsylvania Department of State on Oct. 10, 2024, as Western Hospitality Partners — Jermyn LLC before changing to its current name six months later.

Raymond Rinaldi, attorney for Archbald 25 Developer LLC, answers questions from the public during the hearing for the organization’s proposed “Project Gravity” data center campus at Valley View High School on Tuesday, Jan. 06, 2026. (REBECCA PARTICKA/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER)

Raymond Rinaldi, attorney for Archbald 25 Developer LLC, answers questions from the public during the hearing for the organization’s proposed “Project Gravity” data center campus at Valley View High School on Tuesday, Jan. 06, 2026. (REBECCA PARTICKA/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER)

Project Gravity will have seven two-story-tall data centers, each with a roughly 135,000-square-foot footprint — exactly 138,000-square-feet per floor according to the developer’s joint permit application — and rising to up to 70 feet tall, Rinaldi said during the presentation. A high-tension, 500-kilovolt power line divides it from an adjacent property, Rinaldi said.

Matt Bixler, who heads ARM Group’s natural resources department, told the crowd his company first went to the property in December 2024 when a team of biologists walked the site to get an understanding of the land, its topography and any resources present. They returned to the site in March with a team of biologists who looked for aquatic resources like streams, wetlands and floodways, he said. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers determined the project was not under its jurisdiction because the aquatic features don’t leave the site, leaving it under the jurisdiction of the DEP, Bixler said.

While the presentation itself largely covered publicly available information, representatives of the data center developer revealed additional details about the project in their responses to concerned residents.

Community members listen to representatives from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and for Archbald 25 Developer LLC during the hearing for the developer’s proposed “Project Gravity” data center campus at Valley View High School on Tuesday, Jan. 06, 2026. (REBECCA PARTICKA/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER)

Community members listen to representatives from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and for Archbald 25 Developer LLC during the hearing for the developer’s proposed “Project Gravity” data center campus at Valley View High School on Tuesday, Jan. 06, 2026. (REBECCA PARTICKA/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER)

Utility use

Derek Sutcliffe asked for assurance that “the infrastructure and supply costs won’t be passed onto residential customers” and contended data centers could use 1 million gallons of water per day. In response, Rinaldi told him they requested and received a will-serve letter from Pennsylvania American Water for approximately 360,000 gallons per day. That means if it draws its maximum volume of water daily, Project Gravity will use enough water to fill an Olympic-sized pool about every other day.

Sutfcliffe followed with a question about how heat and contaminants would be removed from the cooling water.

Justin Moceri, the civil engineer for the project from Kimley-Horn, said the wastewater will be sent to the Lackawanna River Basin Sewer Authority wastewater treatment plant, and because it’s not an immediate pass through, the water will sit for a period of time before it’s discharged from the plant, allowing it to cool, he said. Amy Bellanca, the program manager in the DEP’s clean water program, added that the data center is considered an industrial user and would include oversight from the federal Environmental Protection Agency as part of the LRBSA’s industrial pretreatment program.

Sutcliffe also asked about noise mitigation, with Moceri responding that they are committed to 55 decibels during the day and 45 decibels at night to comply with Archbald’s noise standards.

“We’re basically going to implement whatever noise abatement measures we need to to comply with the borough’s standards,” Moceri said.

Resident Tamara Misewicz-Healey pointed out the borough’s noise ordinance does not include regulations for low-frequency sounds below what humans can hear, measured as dBCs.

“That’s the deep noise that you could feel, the one that vibrates, that has sleep disturbances, causes anxiety, cognitive dysfunction in children, and it has actually linked to cardiovascular issues in the long term,” she said. “We have nothing to protect us for that, or even to look at it.”

Drawing from a list of 31 questions she submitted to the DEP, Amanda Russell asked the developer how the data centers could affect local water and electricity.

“Will we have lower water pressure?” she asked. “Will there be brown out(s)?”

Rinaldi responded that they are using public water supplied by Pennsylvania American Water, which is regulated by the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission that sets the rates. Rinaldi added that his client has to install a large water tank “to increase the pressure that is not currently servicing the borough of Archbald and surrounding communities.” Plans for the project include a 1-million-gallon above-ground storage tank for noncontact cooling water.

“My client has to make a significant investment, which they’ve committed to with Pennsylvania American Water, to install the pump stations because the water has to come from the Lake Scranton reservoir and travel north,” Rinaldi said, explaining people mistakenly thought the water would be pumped down from the Carbondale area. “Pennsylvania American Water will not commit to servicing us unless we make these significant and costly improvements, which, once again, not only benefit my client, but benefit the system as a whole.”

Russell also asked about a previous remark during the meeting that the data centers did not yet have a tenant, which Rinaldi said, “We’re in negotiations with tenants, and we currently can’t comment on the specific tenant at this time.” However, they would not construct the data centers without a tenant, Rinaldi said.

When asked about specifics like air emissions from the diesel generators used for backup power or whether they would use a closed-loop system for cooling, the data center representatives said they were unable to answer because that is tenant specific, with Mocari saying, “Unfortunately, this is a speculative campus, so we can’t really dictate what the end users’ technology will be for cooling.”

Rob Mattise raised concerns about occasional droughts and who would get access to the water during one.

Brian Yagiello, the DEP’s program manager for its safe drinking water program, said Pennsylvania American Water looks at its available water resources when it receives a proposal to see if it can provide service, which the utility confirmed it could. PAW has the capacity to draw 33 million gallons per day from Lake Scranton, and during a drought, it has a contingency plan ranging from voluntary conservation to a governor-declared drought emergency, Yagiello said.

Impacts and transparency

Former Valley View High School Principal James Timmons, who retired from the district in 2011, questioned how data centers will impact the community’s long-term health, referencing diesel emissions, heat, water usage, noise and light.

Citing his time as a district principal, Timmons noted the close proximity to schools. The Valley View intermediate, middle and high schools on Columbus Drive are all located in the vicinity of the data centers.

“Could you guarantee me and the people here — I mean this very respectfully — that no harm will come to students, families that have homes close by, breathing in particulates that could harm them as 5, 10, 15, 20 years from now?” Timmons said. “Would you have your children live in this area with data centers close by, and they were going to breathe in emissions that could be harmful? And I’m not saying they are harmful.”

Rinaldi said the emissions will be regulated by a required air quality permit with the DEP.

Mark Wejkszner, the program manager for the DEP’s air quality program, said the department won’t issue a plan approval unless it meets state and federal regulations, which are based on health standards.

After recognizing both Mullins and Brown in attendance, Monahan invited Mullins to speak. The state representative from Blakely asked DEP officials about open meeting requirements for permitting data centers. Pamela Kania, the DEP’s program manager in its waterways and wetlands program, said there are different requirements for different permits, but for joint permits like what Project Gravity is seeking, there is a 30-day comment window where they can consider holding a public meeting or public hearing.

State Rep. Kyle Mullins steps up to the mike to ask DEP and the developer’s representatives questions during the hearing for the proposed Project Gravity data center campus at Valley View High School on Tuesday, Jan. 06, 2026. (REBECCA PARTICKA/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER)

State Rep. Kyle Mullins steps up to the mike to ask DEP and the developer’s representatives questions during the hearing for the proposed Project Gravity data center campus at Valley View High School on Tuesday, Jan. 06, 2026. (REBECCA PARTICKA/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER)

Mullins said state legislators developed data center regulations to protect consumers through openness and transparency, and legislators could consider making public meetings a new requirement to address the emerging industry.

“I understand the overwhelm out there — it seems as if every other day there is a new application or a new data center proposed,” Mullins said, adding that he shares the concerns of those who don’t want data centers in every corner of the valley. “But I do think that the decisions that are being considered from developers, regulators, to local officials are best done in the light of day.”

The comment period for Project Gravity’s water obstruction and encroachment joint permit continues through Jan. 20. Send written comments to the attention of Pamela Kania, P.E., program manager, Waterways and Wetlands Program, DEP Northeast Regional Office, 2 Public Square, Wilkes-Barre, PA 18701-1915 or by email to ra-epww-nero@pa.gov.