“Aboard scores of vessels, from the little fishing schooner and pilot boat to the great transatlantic liner, a life-or-death struggle with the elements is being waged with heroism none the less real because it is in self-defense and none the less admirable because it cannot always divert disaster.”

(Taken from an article in the first issue of National Geographic Magazine, September 22, 1888, by Edward Everett Hayden, U.S.N. Marine Meteorologist, and a founder of the National Geographic Society.)

As a trained naval officer and meteorologist, Edward Hayden knew a lot about the North Atlantic, or as much as could be known in his day. But the year 1888 impressed even him with its severity.

His article focused on a storm in March of that year usually associated with the Great Blizzard of 1888. But one of the great maritime dramas that Hayden did not get a chance to chronicle took place three months after his article appeared. And its final chapter could not be written until many years later.

The SS Allentown

Heather Knowles, Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions

The SS Allentown was not one of the famous ocean greyhounds that dot the pages of maritime lore. She was a humble collier, one of 14 built for the Reading Railroad to carry the cargo of anthracite to ports primarily along the New England shore. Listed as hull number 190, she was built at Philadelphia’s William Cramp & Sons Shipyard and launched in June of 1874.

The following information about Reading’s coal fleet comes from an article that appeared on September 24, 2014, in the Reading Eagle newspaper by reporter Ron Devlin. According to Devlin the Reading Company built colliers between 1869 and 1874. Many people at the time thought the idea impractical but by 1878 they were delivering to ports as far-flung as Maine and Panama. Most of it was delivered between New York and Portland, Maine.

“The coal was transported by train from Pottsville through to Philadelphia where it was loaded in the ship’s hold,” Devlin writes. “Loading was fast and the ships were only in port overnight. Unloading was done with huge buckets lifted into the hold by a huge crane. It would take about 11 hours to unload a ship.”

In 1873 the collier Pottsville was selected to carry the Reading Railroad’s exhibit across the Atlantic to the Paris International Exhibition, aka World’s Fair. The doughty little steamer made the crossing safely in 16 days.

The first colliers were the Rattlesnake, Centipede, Achilles, Hercules, Leopard and Panther. Allentown was a part of the second fleet launched in 1873-1874. Her sisters were Reading, Harrisburg, Lancaster, Williamsport, and Pottsville. That same year two others, Perkiomen and Berks, were launched by John Roach & Son of Chester.

Certificate of enrollment for SS Allentown

Heather Knowles, Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions

The earliest of those ships carried between 500 and 1000 tons of coal. Later 1600 tons of coal was taken from mines at Pottsville.

According to the Massachusetts-based Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions, which would later play a key role in figuring out what happened to the Allentown, the ship was a 1583 gross ton iron collier that measured approximately 250 feet in length with a breadth of 37 feet and a depth 20 feet. Her crew numbered 18 men.

The Allentown and her sisters had been built to serve a vital purpose. When the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad was created it was not supposed to own coal mines. But the behind-the-scenes dealings of its president Franklin Gowen led to the company acquiring some. This led the Reading into conflicts by the late 1860s and early 1870s with those miners who wanted to create a union. By the late 1870s, armed troops were sent into the streets of Reading to force the men back to work.

In its early days the Reading Railroad moved its out-of-state coal on sailing ships or schooners. It was eventually decided that not enough coal could be moved this way, and the idea of colliers was created in the post-Civil War years.

The Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Terminal, 12th & Market Streets, Philadelphia, PA. The Cooper Collection of American Railroadiana

Cramp was an obvious choice for the colliers to be built. William Cramp, the firm’s founder, was a native of Philadelphia. He founded the shipyard in 1830. In 1855 his sons Charles Henry and William C. joined him as partners. Later, in 1872, his younger sons Samuel H., Jacob C. and Theodore were added. They were incorporated under the name of the William Cramp and Sons Iron Shipbuilding and Engineering Company. In the 1890s the Cramps would build several battleships that would power the U.S. to victory in the Spanish American War.

It was on November 21, 1888, that the SS Allentown, carrying a heavy load of 1650 tons of anthracite, left the Reading’s Philadelphia port facilities, bound for Salem, Massachusetts. Because the collier had no survivors, no one can say what the crew of the Allentown was thinking about the severe weather they had to know they were going to be sailing into. The Monthly Weather Review for November 1888 noted that eleven weather depressions, i.e. storms “have been traced north or near Newfoundland; two first appeared northeast of the Windward Islands.’’ Three apparently emerged over mid-ocean.

All in all, the North Atlantic was a haven for severe storms that November and the SS Allentown was heading directly into it. Was the captain of SS Allentown an employee of the Reading Company? Were the rest of the crew experienced or just hired for this voyage? What would they have been paid for on a voyage like that? Did any of them try to escape by lifeboats? All these questions of course will never be answered.

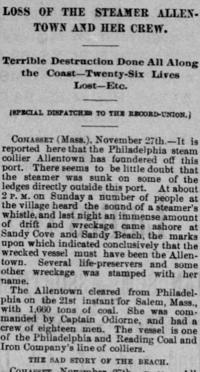

Newspaper article about SS Allentown’s demise; Sacramento Daily Union 28 November 1888 — California Digital Newspaper Collection

Heather Knowles, Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions

It is estimated that between 15-20 ships were wrecked between Scituate and Boston during that storm. Witness accounts and debris led to the belief for many years that SS Allentown foundered off Cohasset, Massachusetts. It was here that a large part of the debris field was washed ashore and that the one presumed crew member’s body was found.

For over 120 years the exact location of the SS Allentown was disputed, and the mystery remained a mystery. In the 1890s the Reading Railroad adopted a new method of transporting coal using barges pushed by tugboats. It moved a lot more coal a lot faster.

But, clues about the fate of the Allentown emerged around 2010. Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions (NADE) has an account of what happened on its website.

The group said it was in September of 2010 that NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS) deployed a sonar system to map the northwest corner of Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. That was when an initial part of the wreck was detected, although no one knew at the time that it was the Allentown.

Heather Knowles, of Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions, after one of the dives to the Allentown wreckage site

Heather Knowles, Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions

Over the next several years, Heather Knowles and David Caldwell of NADE assumed project leadership. Several dives later, they had located all three parts of the sunken ship. Here’s how they described it, in an account from 2019:

“The Allentown was found some distance from the area of Minot’s Light and rests in over 200 feet of water much further to the north of Cape Ann. To date the exploration project has spanned four years. Poor weather and difficult conditions at the wreck site hampered progress. The wreck consists of three distinct sections and coupled with low visibility, deep water, strong current exploration of the Allentown has been challenging and slow.”

Underwater wreckage of the SS Allentown

Heather Knowles, Northern Atlantic Dive Expeditions

The dive teams were able to capture many photos and videos of the site. They also note that the Allentown is a historic wreck, and as it is a gravesite, the wreck should remain undisturbed and treated with respect.