Life, death, youth, and aging intersect uniquely in “Kimberly Akimbo,” a play about a 16-year-old girl with a genetic disease that accelerates her aging process so that she has the body and physical condition of someone more than four times her age.

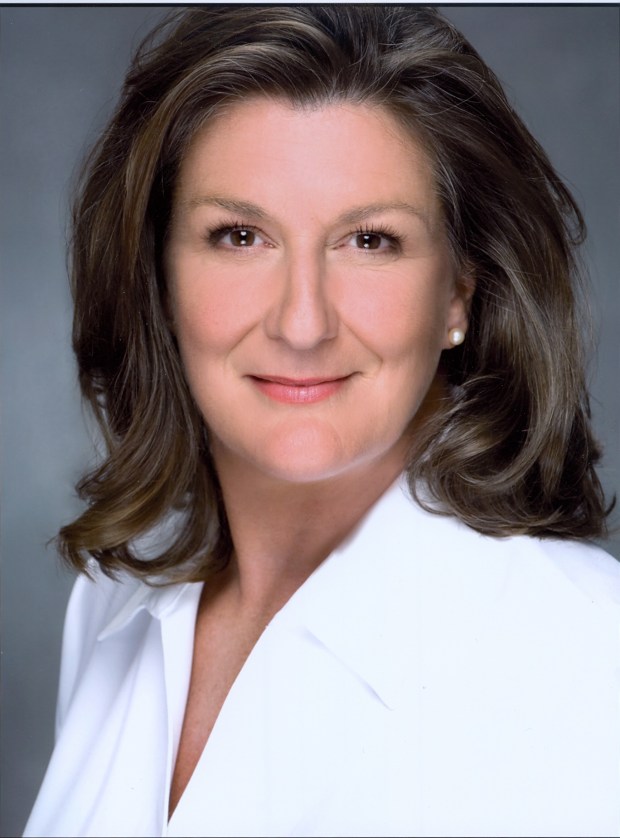

“She’s a 16-year-old in a 70-year-old’s body,” says Ann Morrison, an actor and teacher of vast and varied experience, who plays Kimberly in the national tour of “Kimberly Akimbo,” a Tony-winning musical coming to Philadelphia’s Academy of Music on Tuesday for a two-week stay as part of Ensemble Arts Philly’s Broadway season.

Morrison, about half a year shy of 70, says, “I don’t have to act to understand this character. I only have to show up.”

Of course, that’s partly facetious. In conversation, Morrison is funny, upbeat, and and has much to say about aging but also about feeling vibrant, optimistic, and fascinated by the process as she does.

She is also a consummate professional who not only performs but teaches acting, especially to people interested in solo performance ranging from one-person plays to cabaret and other individual expressions.

As Morrison points out, her situation is different from Kimberly’s in one significant way.

In the play, Kimberly tells her best friend 16 is the age at which she reaches the life expectancy for her disease, one devised by “Kimberly Akimbo” author David Lindsay-Abaire for his play and the musical version of it coming to the Academy, but akin to progeria.

Jim Hogan, right, along with ‘Kimberly Akimbo’ castmates Ann Morrison and Miguel Gil will bring the show to the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. (COURTESY OF JOAN MARCUS)

Jim Hogan, right, along with ‘Kimberly Akimbo’ castmates Ann Morrison and Miguel Gil will bring the show to the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. (COURTESY OF JOAN MARCUS)

“She is 16 years old and wary of death and what she might be leaving behind, but she is young in years, youth-oriented. She wants to hang out with her friends and have a good time.

“She wants to enjoy being 16. She doesn’t want to be a victim. She is optimistic.”

Meanwhile, Morrison is doing things, some physical things she has not done since she was a teen, age 15 to be exact. Ice skating is one.

“The show has a scene in which Kimberly ice skates on what for us is a polyurethane floor. It had been several decades since I’d ice skated. It is part of the show, so I work to do it like I did when I was 15.

“Then I’m reminded of my actual age. By leg cramps for one thing. I ask myself, ‘What did you just do?’ It was good to do something for the first in a long time. There may be consequences, but it’s all part of living.

“I enjoy aging. I always admired older people. When I was 5, I thought old people were beautiful with their gray hair. Now I’m fascinated by aging. Especially as I experience it.

“In any case, I’m not depressed by it, and neither is Kimberly. She has moments of concern and grief, even worry about her family. She ages rapidly in one year, but she is also a teenager.

“She expresses it well in the song, “Before I Go,” where she contends with what is happening and accepts reality and what she can’t fix. (Composer) Jeanine Tesori and David Lindsay-Abaire capture a lot in that number.”

Jeanine Tesori and David Lindsay-Abaire accept the award for best original score for “Kimberly Akimbo” at the 76th annual Tony Awards on June 11, 2023, at the United Palace theater in New York. (Photo by Charles Sykes/Invision/AP)

Jeanine Tesori and David Lindsay-Abaire accept the award for best original score for “Kimberly Akimbo” at the 76th annual Tony Awards on June 11, 2023, at the United Palace theater in New York. (Photo by Charles Sykes/Invision/AP)

Ann Morrison has been performing for a lifetime. She originated the role of Mary Flynn in Stephen Sondheim’s “Merrily We Roll Along” and has appeared on Broadway and in various theaters since.

She and her former husband, Blake Walton, have done a lot of theater in Sarasota, Fla., which is home when Morrison is not on the road.

“We dumped the marriage but kept the friendship,” Morrison says. “We’ve also decided we don’t live in a drama. We live in a comedy,”

That includes a lot of work. Morrison has worked constantly throughout her career, taking roles and making her own way.

“There is always a story to tell and ways to tell it,” the says.

She talks about loving solo theater. She has devised shows she can bring to various venues and helps others learn to create and take the leap to bring their show to a theatergoing public.

Her solo career can be a cabaret of standards at a Manhattan nightclub, a play that explores one character or one performer playing many characters. She says she finds solo work challenging and liberating.

She also quotes of of Sondheim’s lyrics from “Merrily We Roll Along” — “You have to burn your bridges now and then” — and talks of expressing oneself and telling the many stories that make up the world.

In terms of “Kimberly Akimbo,” she says she is grateful to the show’s director, Jessica Stone, for not only letting her find her personal way of playing Kimberly but encouraging it.

She also speaks highly of her casemates and says she was warmed by the way they welcomed her when she joined their tour.

KYW radio reunion a walk through history

Last week’s Broadcast Pioneers luncheon marking the 60th anniversary of KYW Newsradio (1060 AM, 103.9 FM) was tantamount to a warm, happy reunion of anchors, reporters, editors, and techs from several eras.

Hugs abounded, pictures were snapped, memories were shared and all seemed delighted to be in one another’s company to reconnect and reminisce.

More than one alumnus quipped it was great to meet at a celebration and not a funeral.

It was fun to witness. I was fun to experience, especially for a listener like me who got to match faces with names, and vice versa, and loved hearing the various war stories several from what has to count as one of the region’s primary news sources had to tell.

Lauren Lipton, whose name I always hear preceded by “at the editor’s desk,” told a hilarious story about when of her first assignments when she came to KY’ as a reporter.

Lipton was told to cover the Army-Navy game, a major national event at the time and always held in Philadelphia. Football wasn’t necessarily her beat, but she was sent to the game and received a press pass.

On that said in larger-point capital letters, in red ink, “Ladies Will Not Be Permitted in the Press Box.”

Lipton couldn’t miss the notice, but the Army-Navy game was her story, and she went undaunted to the press box. She sought the person she called the “bouncer” while relating this episode.

She showed him the restriction, said she was representing KYW, and informed him she intended to stay.

She met no resistance. The gatekeeper said, “Oh, this doesn’t mean you.”

“Oh, then who does it mean?”

“Well, you see the guys in the press began asking their girlfriends and relatives to join them in the press box. It got to be too much, so we prohibited admission to women. But that doesn’t apply to you.”

“Then why does it say, ‘ladies?’ Why doesn’t it say, ‘Guests will not be admitted?’ ”

Lipton was told she made a good point. The “bouncer” was apologetic to the point of going overboard. He asked Lipton if she wanted anything.

“Yes” she said. “I want to to take that line off the press pass and do it now.”

And he did.

Lipton’s story goes beyond revealing the ignorance of a press pass mentioning “ladies” as opposed to all nonpress of any variety. It tells about the fight women in the 1970’s had to wage to claim their place in journalism and broadcasting.

My career began in the ’70s, and I witnessed and listened to many incidents involving women who were told they could never cover news or be on television and radio.

Her tale, especially as she told it, was simultaneously humorous and daunting, using an example that wreaks of the obtuseness women faced while showing how entrenched dismissal of and discrimination towards women was.

Tony Hanson, who spent 37 years at KYW, talked about the people he met and obstacles he faced after being sent to ground zero on Sept. 11, 2001.

Even as a reporter, Hanson had to navigate how he got from one point to another.

Toward the end of the day, he was approached by a family that included a baby wrapped in the blanket. They were among those trying to get to safety and away from the World Trade Center area.

They asked Hanson if he could help them by giving them a ride in his car.

He said we would try to get them to the nearest checkpoint, which seems the best that could be managed in a chaotic situation. He also asked for a favor. He asked if he could see the baby.

The child’s innocence moved him. Here was someone who could not understand anything but was in the middle of an historical event.

The image of the child looking at him stayed with him. As did meeting a family who had to deal with the events at hand.

Relating his encounter with the child to his daughter by telephone was the time Hanson shed reporters’ armor and reacted to what he had spent the day chronicling.

Richard Maloney, in relating his coverage of the Three Mile Island incident on 1979, spoke of something that every reporter encounters, an official spokesperson who didn’t quite tell the truth.

“He was lying, and I knew he was lying, and he knew that I knew he was lying.”

So, Maloney reveals, did the Pennsylvania governor at the time, Richard Thornburgh, and the sitting president, Jimmy Carter, who was versed in nuclear physics.

Not only did Maloney bring up one of a reporter’s worst dilemma, receiving information you know is false, but he reminded the Broadcast Pioneers of a time when a governor or president had broad knowledge that could be useful in a tense situation.

Jay Lloyd was the panel moderator for the program. He, who will soon be age 91, told his colleagues he looks forward to seeing them at the 70th anniversary, 10 years from now.

Veteran of stage in warm, funny Hedgerow farce

Marcia Saunders has been a part of Philadelphia theater history since the latest era of it began with the founding of local companies in the 1970s.

Marcia Saunders (COURTESY OF HEDGEROW THEATRE)

Marcia Saunders (COURTESY OF HEDGEROW THEATRE)

Saunders has performed with most of the troupes that formed since then, but she is known for the dozens of performances she’s given at Malvern’s People’s Light, where she has been a member of the resident company pretty much since it was formed.

The first theater she remembers entering and getting a feeling she was in someplace holy and home is Rose Valley’s Hedgerow Theatre where Saunders is currently appearing in two-hand Irish farce, Marie Jones’s “Fly Me to the Moon,” with her friend and frequent co-star Susan McKey, another associated closely with People’s Light, particularly their annual pantos.

Saunders even jokingly refers to McKey as Ms. Panto at one point in our talk.

Marcia and I have known each other for 50 years. When I called her for the interview, she asked, “What is it we can possibly not know about each other or haven’t discussed in all off the conversations we’ve had since we were in our twenties?”

A life in the theater is one. “Fly Me to the Moon” for another.

Fifty years that have flown by in a way with Marcia constantly involved in a play and I seeing more than 100 of them a year.

Take that first step into Hedgerow, when she was a teenager.

“I walked into the old entrance, the one at the top of the theater, right off the road, and felt immediately as I if I’d entered a sacred place. I was 17. I met Janis Dardaris — another of Philadelphia’s seminal actors — that day. What I remember most the powerful feeling I had just being at Hedgerow.

“Now, 50 years later, I’m on its stage again, and in one of the most challenging parts I’ve encountered in a while. Suzy and I are flexing our muscles on this one.”

Ironically, Marcia recalls having played McKey’s part in a sketch of “Fly Me to the Moon” about 10 years back.

“I’ve done so many plays since then, and so many characters, I didn’t recall at first, which is good because that allows me to come to the piece fresher.

“Susan and I saw the challenge right away. We began meeting to run lines months before rehearsals started. We came to that first rehearsal off-book so we could work on the harder part, bringing the two woman we play, caregivers who tend to one man as employees of a service, to full life.

“That’s the challenge because Marie Jones wrote a farce, and we have to let the farce come through without doing anything that forces the comedy.

“Our director, Emma Gibson, asked us to watch a documentary, and it was clear that going directly for comedy is the wrongway to go in a farce. Our characters are real people who don’t know they’re being funny or in a situation that can be presented comically.

“We’ve worked hard to preserve the reality and personalities of our characters while letting the humor Jones provides come through. It’s the same with any part, find who the person is and what drives her to do what they do.”

Marcia and I spoke the day before “Fly Me to the Moon” opened, and she mentioned Gibson was still honing fine points and giving her and McKey helpful notes.

One thing I learned Marcia and I have in common is we learned about theater by watching it, not studying it academically. She spoke of getting a true education when she attended London’s LAMDA and show dozens of West End and Fringe plays.

I learned by reading plays and seeing more than 100 of them a year since 1971.

By appearing constantly at People’s Light, Hedgerow, and other houses, Marcia has become a staple of Philadelphia theater.

“I came to People’s Light in 1976 and found a home. More than that, I found a family. I have been part of a company that has performed and shared lives together for 50 years.

“Susan McKey is part of that. It has been joy from the beginning. I may not have predicted many of us would be working together 50 years later, but the work, the relationships, and the community has made for a happy fulfilling life.”

I’ve seen “Fly Me to the Moon” since Marcia and I spoke, and it is as warm and funny as she described it. And a little naughty, too.

Also, Marcia, Susan McKey, and Janis Dardaris will be in the cast of “Steel Magnolias,” directed by Abigail Adams, at People’s Light in 2026.

“Fly Me to the Moon” runs through Nov. 2 at Hedgerow.

Originally Published: October 19, 2025 at 7:00 PM EDT