When I first came to the Lehigh Valley in 1981, I knew little of its history. One of my first “teachers” was the late Lance Metz. His passion was the region’s industrial history, which he felt had been overlooked and neglected by the emphasis on New England. As I spoke to Lance, I also got to know a circle of fellow enthusiasts that shared his interest. Among the first mentions was the late Kurt Zwikl. “Frank, you have to meet Kurt,” he would say frequently.

As I had begun to write history-related stories, I assumed we would eventually cross paths. But still I was a little surprised in the late fall of 1985 to get a phone call from Zwikl. He had been in Florida on a family vacation and had uncovered a very interesting local tie to an event in Florida history. Was I interested in talking about a possible story? I said I would be very interested and set up a time to go to his home.

Kurt Zwikl

PA House of Representatives Archives

This led to a story for the Morning Call newspaper, some of the details of which are included here. Others are from a variety of historical sources, several of which are online which were not generally available in 1985.

They outlined more clearly the reasons why the former Lehigh Countian, 23 year old Thomas Knarr, might have found himself in Florida in 1835 with a military unit engaged in warfare with the Seminole Native American tribe, and how it eventually led to his death along with that of almost 100 of his fellow soldiers, in a battle that is still commemorated as part of Florida’s history.

It all began with a Zwikl family vacation visit to that state. With them was Kurt’s father, William “Bill” Zwikl, well known for his long-time career as a photographer for Hess’s Department Store. Along with a stop at Disney World and NASA, Kurt had a desire to see the Dade Battlefield site.

Here he read a list on the stone monument of those soldiers who were killed in that 1835 encounter with the Seminoles and a group of African American enslaved men who had fled from the nearby slave holding state of Georgia.

Dade Battlefield Historic State Park

Trail of Florida’s Indian Heritage, Inc

Kurt admitted to me that day he was stunned to read of the number of young natives of Pennsylvania who died in battle there. The most surprising was that of Private Thomas Knarr, whose birthplace was listed as Lehigh County. As a student of local history Kurt was fascinated by the presence of this young man so far from the place of his birth, traveling to die in a distant corner of the country. Returning home, Zwikl began to find out what he could.

Acquiring a copy of Knarr’s enlistment papers, Zwikl discovered some intimate details about the young soldier. Knarr’s occupation was listed as laborer. He was 6-feet, 4 inches tall, had hazel eyes, fair skin and black hair. Most probably Thomas was from Lowhill Township where a Knerr or Knarr family are known to have settled in the mid-18th century. Thomas may have been the son of Abraham Knerr or Knarr (1758-1840) who was known to have had 13 children.

At that time Kurt told me he was puzzled. The enlistment papers showed Knarr had settled in Utica, New York, so far from home. He speculated that it might have been because Knarr was looking for work.

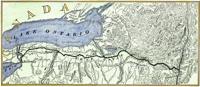

Online sources not available in 1985 suggest that Zwikl’s speculation about Knarr’s presence far from home was probably correct. According to the website for Oneida County’s Freedom Trail, Utica and Oneida County was a prosperous, canal-centered community. By its ties to the Eire Canal, it was linked to what was then the nation’s major “highway” between the east and the west. Perhaps Knarr worked on the Eire Canal, which already had industries sprouting along its banks.

Erie Canal map, c. 1840

“Certain citizens of Onedia County and particularly Utica played a significant role in promoting the abolition of slavery,” notes the Oneida Freedom Trail. Local religious figures with roots in New England held strong views on the subject. It had been abolished in New York in 1827.

Others in Utica were just as strongly in support of keeping it for commercial reasons. Why confuse the issue? It was also that they feared dividing the country. It was a southern “peculiar institution”; why split the country over it? A year after Knarr left Utica, a large riot broke out between pro- and anti-slavery forces, among one of the largest of the pre-Civil War period in the north.

It is of course impossible to know with any certainty exactly what position, if any, Knarr held on the issue. As a healthy young man, he may have just wanted to see another part of the country. But the fact that he was going to the south to a state where the army was attempting to put down a rebellion that included armed, formerly enslaved Black people may reflect Knarr’s position on the issue.

When Knarr arrived at Fort , now Tampa, he was part of the Second Artillery Regiment Company C. Most of his fellow soldiers were either Irish or Scottish immigrants or working-class Americans. The officers were professional soldiers from southern families. Their commander was Major Francis Langhorne Dade. His family had Virgina roots that went back to 1645.

Florida had been a part of the Spanish Empire since the 1500s when the explorer Ponce De Leon came looking for the Fountain of Youth.

17th century Spanish engraving (colored) of Juan Ponce de León

For a time, it was under the sway of the British in the 18th century but was returned to Spain following the American Revolution. By the 1790s slave holders in Georgia were complaining that their slaves were running off to freedom into Florida. Spain, tied up in wars in Europe and an occupation by Napoleon’s French Army, had neither the time nor the inclination to attempt to stop it.

In 1816 General Andrew Jackson, a slave-holding, Indian-hating soldier and future president, decided to take it into his own hands. From 1816 to 1817 he ran over the colony, butchering Indians and rounding up the sons of formerly escaped slaves, their fathers largely having died, and turning them over to their fathers’ former masters. By 1819 Spain, loaded with debt and rebellion in its colonies around the world, decided to make a treaty with the U.S. John Quincey Adams, Secretary of State, thought it was a good deal and so did southern settlers who came pouring across the border, most totally ignoring treaties made with the Seminole and taking over any land they wanted.

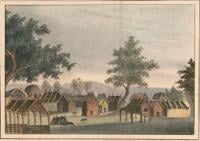

Seminole village, prior to the Second Seminole War

“Lithographs of events in the Seminole War in Florida in 1835”

Tensions rose with the Seminoles especially when the children of mixed marriages between the Seminoles and slaves were turned over to slave traders. Seminole Chief Osceola vowed vengeance but insisted on waiting for the right moment. In the meantime, Thomas Knarr lived out the life of a garrison soldier. Drill, drill and more drill was the order of the day. Spit and polish and artillery practice were routine.

Finally, word came of trouble. Fort King, roughly 100 miles away and now the city of Ocala, was hearing rumors of actions by the Seminoles. They felt the need to be reinforced. Major Dade felt he had to march in a show of force. He had no doubt that the savages would flee at the mere sight of his troops. To add to the impression, he had the artillery crew bring a cannon along. This may have been where Knarr was when the force left Fort Brooke on December 23, 1835.

Under the fading mid-winter sun, roughly 40 miles from Fort King, Major Dade, white gloved hand on the pommel of his saddle, turned to his men. “Have a good heart, our difficulties and dangers are over now, and as soon as we arrive at Fort King, you’ll have three days to keep Christmas gaily.’’

Moments later a shot was heard, and open gunfire was all around them. Fire seemed directed at Dade. One account of the battle described it this way:

“Francis Dade, broad shoulders erect, slumped gently in his saddle like a sack of grain cut in the middle. His beard grazed the mane of his horse as his body fell and slipped to the ground. Dade had had been shot through the heart and was quite dead.”

Death of Major Dade, created in 1836

Volleys of bullets poured from the woods, wiping out 50 men. Under the circumstances the troops performed well and were able to make a small breastwork. But more Seminole charged out of the woods firing. They retreated and 50 Black men rode out of the woods. Former slaves and sons of slaves wreaked vengeance on those whose fathers once whipped their fathers.

This was the start of the Second Seminole War that officially ended in 1842. But in truth some believe there never was an official surrender. The Seminoles retreated into the swamps. And the bones of Thomas Knarr rest with his comrades far away from the Lehigh County he once called home.