On the morning of Jan. 3, phones across Pittsburgh began buzzing before sunrise, lighting up with WhatsApp messages and calls from relatives in Venezuela.

Those buzzes would set off weeks of uncertainty, emotional swings and mixed feelings for Venezuelans in Southwestern Pennsylvania, many of whom left the country because of its repressive leadership, though some now face an uncertain welcome as U.S. immigration policies shift.

“It’s some of the best, Pulitzer-worthy local independent journalism in the States right now.”

— Public Source member Laura H.

Join thousands of Pittsburghers by signing up for Public Source’s newsletter today.

A boy stands on a fishing boat with the Cardon oil refinery in the background in Punta Cardon, Venezuela, on Jan. 14. (Photo by Matias Delacroix/AP Photo)

A boy stands on a fishing boat with the Cardon oil refinery in the background in Punta Cardon, Venezuela, on Jan. 14. (Photo by Matias Delacroix/AP Photo)

Carlos Roa, a Venezuelan American journalist and editor based in Pittsburgh, was half-asleep in bed, expecting an uneventful Saturday, when his spouse pressed a phone close to his face.

Earlier that morning, a U.S. military operation had captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, flying them to the United States to face federal charges.

Roa reached for his glasses and his phone, eyes still adjusting as he reread headlines and flipped between outlets, trying to determine whether he was taking in confirmed reporting or misinformation.

Then he noticed where the bombs were landing. One location stopped him: Fuerte Tiuna, the major military complex in Caracas, where U.S. troops captured Maduro. Roa’s cousin lives nearby.

“So of course I rushed to call him,” Roa said.

Jesus Linares, right, removes a painting of independence hero Simon Bolivar at his home, which he says was hit during U.S. military operations to capture Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, in Catia La Mar, Venezuela, on Jan. 4. (Photo by Matias Delacroix/AP Photo, File)

Jesus Linares, right, removes a painting of independence hero Simon Bolivar at his home, which he says was hit during U.S. military operations to capture Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, in Catia La Mar, Venezuela, on Jan. 4. (Photo by Matias Delacroix/AP Photo, File)

The call would not go through. For hours, the internet and phone service were down. Roa replayed the footage again and again, scanning the edges of the frame for familiar buildings. By nightfall, his cousin resurfaced after power was restored. He was OK.

Roa described what followed as a collective exhale.

“We celebrated at home,” he said. “We opened a bottle of wine. We started calling relatives and friends, checking in on them.”

They weren’t toasting the use of military force in their homeland, he said. “It is not a call for violence or intervention, but a response to decades of life under a regime that devastated the country, killed thousands, looted billions, tore families apart, and punished anyone who told the truth.”

Roa said years of repression and displacement have conditioned many Venezuelans to seize moments of relief, even when the broader picture remains unstable.

‘Happiness with the handbrake on’

For many Venezuelans in Pittsburgh, a quarter century of strongman rule carries a looming presence.

Grace Betancourt-Jones, owner of Tu y Yo Café locations in Swissvale, Allison Park and Shadyside, said members of her family were killed during the Chávez era and the early years of Maduro’s rule. Hugo Chávez was president of Venezuela from 1999 to 2013, succeeded by Maduro.

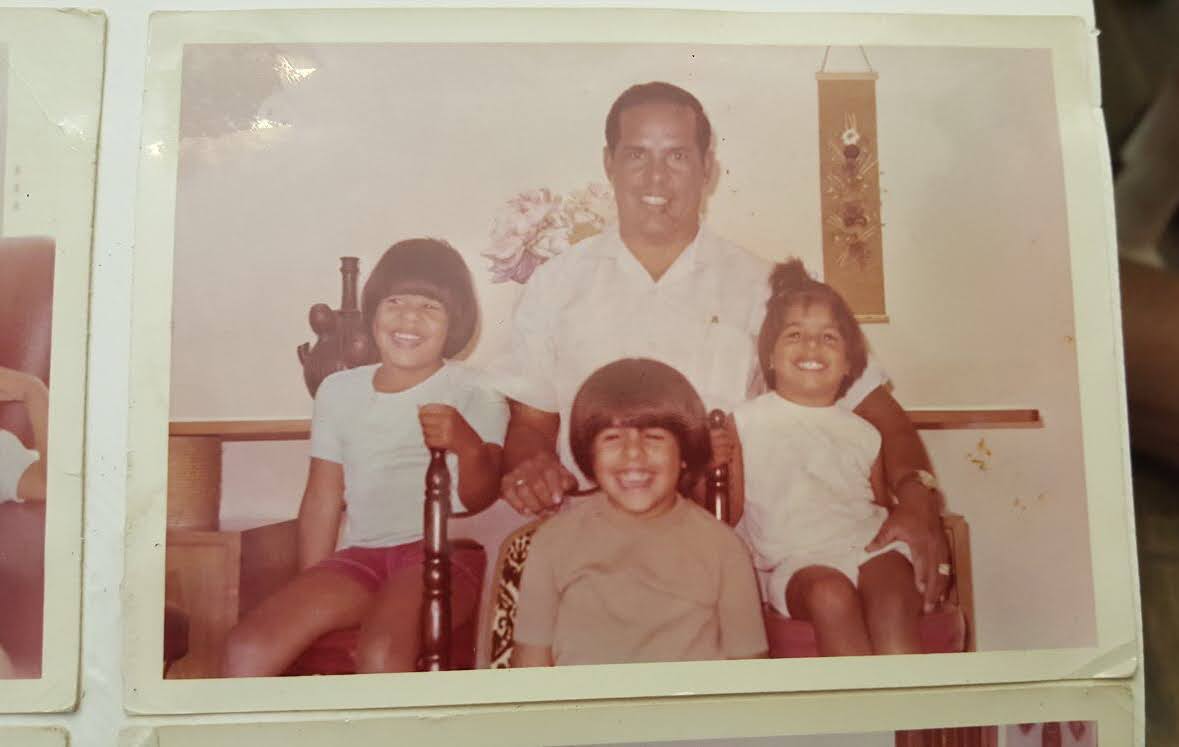

Grace Betancourt-Jones, right, of Fox Chapel, sits with her family in Venezuela at around 5 years old. (Photo courtesy of Grace Betancourt-Jones)

Grace Betancourt-Jones, right, of Fox Chapel, sits with her family in Venezuela at around 5 years old. (Photo courtesy of Grace Betancourt-Jones)

“Many people in my family were killed, shot, raped,” Betancourt-Jones said. “We lost a lot of family members. So yes, I am happy about this news.”

Many area Venezuelans, though, are bracing themselves for what might come next.

“It’s like happiness with the handbrake on,” said Rolando Esser, an Uber driver, artist and aspiring tattooer from Barquisimeto, Venezuela, who lives in the Pittsburgh region. “You don’t know if you should feel completely happy yet or not, because there is so much uncertainty.”

That uncertainty extends beyond the capture itself. The strike and its aftermath have raised renewed questions about civilian harm, accountability and what a political transition in Venezuela could realistically look like, particularly as longtime power brokers remain influential.

Vice President Delcy Rodríguez was sworn in as interim president, a transition challenged by opposition figures and questioned by international observers. Other senior Chavista figures remain embedded in the country’s security and governing apparatus.

Roa said he is troubled by a transition that appears to keep Maduro’s inner circle intact.

“We have a winner: Edmundo González,” he said, referring to the opposition candidate many Venezuelans believe won the 2024 presidential election and whom the United States later recognized as president-elect. But Roa said the transition doesn’t appear to reflect that mandate.

Instead, he said, conversations in U.S. politics often shift quickly to oil, even as Venezuelans remain focused on safety, justice and survival.

A woman who lives near the Cardon refinery hangs clothes to dry in Punto Fijo, Venezuela, on Jan. 14. (Photo by Matias Delacroix/AP Photo)

A woman who lives near the Cardon refinery hangs clothes to dry in Punto Fijo, Venezuela, on Jan. 14. (Photo by Matias Delacroix/AP Photo)

Conversations in Pittsburgh’s Venezuelan community have shifted from politics to concern; family check-ins, flight routes, whether phones are still connecting.

“It’s more like, ‘Did you hear from your mom?’ or ‘Is everyone safe?’” said Alicia Sewald-Cisnero, a Pittsburgh-based bilingual mental health counselor who works closely with Venezuelan families. “People are worried about people.”

Esser said he has been spending more time on video calls with relatives back home, even when there is little new information to exchange.

“Sometimes it’s just to hear a voice,” Esser said. “To say, ‘I’m here. Are you okay?’”

Maria Paparoni and her husband Ivan Cordoba stand for a portrait with their Venezuelan flags on Jan. 15, in their Bethel Park home. The couple, who were lawyers in their home country, fled to the United States with their young daughter after Cordoba was kidnapped by criminal groups when Paparoni refused to issue rulings that would violate the law. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Maria Paparoni and her husband Ivan Cordoba stand for a portrait with their Venezuelan flags on Jan. 15, in their Bethel Park home. The couple, who were lawyers in their home country, fled to the United States with their young daughter after Cordoba was kidnapped by criminal groups when Paparoni refused to issue rulings that would violate the law. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Maria and Ivan: excitement and anxiety

“Venezuela has always been a wound in our hearts,” María Paparoni said.

For Paparoni and husband Ivan Cordoba, co-owners of Pittsabana Roofing in Bethel Park, the news landed inside a life already shaped by the reach of Venezuelan power.

Both are lawyers by training. Paparoni said she served as a criminal judge — one who refused to issue rulings that violated the law.

The consequences, Cordoba said, were immediate when they refused to tip the scales of justice.

“I decided to leave Venezuela after being kidnapped by criminal groups sent by the government,” he said, describing a construction union he said took orders from Argenis Chávez, Hugo’s brother. Cordoba said they were targeted after Paparoni refused to release one of the union’s leaders, who had been imprisoned for homicide.

A man sits on steps decorated with a mural representing the eyes of late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez in Caracas, Venezuela, on Jan. 12. (Photo by Matias Delacroix/AP Photo)

A man sits on steps decorated with a mural representing the eyes of late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez in Caracas, Venezuela, on Jan. 12. (Photo by Matias Delacroix/AP Photo)

“I had to protect my family,” he said. “I realized that in Venezuela, I could no longer keep them safe.”

Cordoba arrived in Pittsburgh in 2017 on a visit. Paparoni and their daughter followed. The family decided not to return.

In Venezuela, Cordoba held a master’s degree in constitutional law. “I was a lawyer with a doctorate in human rights,” Cordoba said. “Now we replace roofs. I never imagined doing this, but it was the opportunity God placed in our path.”

When the news broke, Paparoni said the couple felt both relief and fear — excitement that something might finally be shifting, and anxiety for those still in Venezuela.

Alicia: Bracing for clients in crisis

Sewald-Cisnero, who founded and leads Ayúdate, a nonprofit providing Spanish-language mental health care, came across the news while scrolling Instagram over her morning coffee, nearly scalding herself with the hot liquid.

Her first response was dread.

“Oh my goodness,” she recalled thinking. “There’s going to be an immediate crisis. All my family, friends and clients are going to be in crisis.”

Alicia Sewald-Cisneros sits for a portrait in her office on Jan. 11, in her home in Wexford. Sewald-Cisneros immigrated from Venezuela as a young woman but remains connected to the Venezuelan community through friends who still live there. (Photo by Sophia Lucente for Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Alicia Sewald-Cisneros sits for a portrait in her office on Jan. 11, in her home in Wexford. Sewald-Cisneros immigrated from Venezuela as a young woman but remains connected to the Venezuelan community through friends who still live there. (Photo by Sophia Lucente for Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Her nonprofit focuses on making Spanish-language mental health care accessible, especially to people without insurance, and on reinforcing the idea that mental health is not a luxury. In the days that followed the U.S. action, Sewald-Cisnero listened as Venezuelan clients cycled through a familiar emotional pattern: a surge of hope driven by a glimpse of change, followed quickly by fear that the hope would be taken away again.

She also saw how quickly the moment triggered contingency planning inside immigrant households: plan A, plan B, what happens if an immigration case doesn’t go through, what happens if someone is deported, what happens if return is still impossible even if the regime changes.

The toll, she said, isn’t always labeled as mental health. Instead, it shows up in behavior: “avoidance, obsessing, numbing, spiraling, shutting down.”

Underneath it all is a deeper ache. Even for people who have lived in the United States for decades, moments like this revive the immigrant question of belonging. “I’ve been here for 37 years,” she said, “and then it’s like a reminder: Nope, you don’t belong here. You’re still an immigrant.”

Sewald-Cisnero said cultural stigma still shapes how many Latin Americans seek support. Mental health, she said, remains broadly taboo, even as attitudes begin to shift.

Grace: Providing a place to belong

Betancourt-Jones arrived in Pittsburgh in 1979 at age 13, following her mother to the University of Pittsburgh. Raised by a single mother with three siblings, the family spent their early years sharing a one-bedroom apartment.

“It was hard,” Betancourt-Jones said. “But it was also beautiful for us.”

Born in Caracas, Betancourt-Jones comes from a family shaped by layered migrations, with roots in India, Colombia, France, Germany and Venezuela. Those histories were rarely spoken aloud. What moved between generations instead was food — and the sense of care and connection it carried.

That worldview took physical form in 2019, when Betancourt-Jones opened Tu y Yo Café. The name, she said, means “you and I.”

Grace Betancourt-Jones, of Fox Chapel, sits for a portrait in her café, Tu y Yo Café, on Jan. 11, in Sewickley. Betancourt-Jones opened the café three months ago with the goal of creating community and bringing people together. (Photo by Sophia Lucente for Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Grace Betancourt-Jones, of Fox Chapel, sits for a portrait in her café, Tu y Yo Café, on Jan. 11, in Sewickley. Betancourt-Jones opened the café three months ago with the goal of creating community and bringing people together. (Photo by Sophia Lucente for Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

After the pandemic, and especially in the days following the news out of Venezuela, Tu y Yo became a refuge for Venezuelans and other Latin Americans, a space where people could show up without having to explain context.

More Venezuelans have been coming in to sit together, asking Betancourt-Jones how she is doing and how she feels about the current situation in Venezuela, while the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce has reached out to offer connections to mental health support and counseling.

“In moments like this,” Betancourt-Jones said, “people need a safe space. They need to belong.”

Why caution is shaping public reaction

In Pittsburgh and the U.S., reactions to Maduro’s capture have been split. While some welcome his arrest, others protested U.S. military involvement. In East Liberty, more than 100 people gathered outside East Liberty Presbyterian Church for a “No War on Venezuela“ demonstration.

Roa said Venezuelans in the region are watching events unfold on two fronts at once — what comes next in Venezuela, and what feels safe to say or show here in the United States.

People march on Jan. 11 during a protest on Pittsburgh’s South Side in response to recent shootings involving federal immigration agents. (Photo by Quinn Glabicki/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

People march on Jan. 11 during a protest on Pittsburgh’s South Side in response to recent shootings involving federal immigration agents. (Photo by Quinn Glabicki/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Those concerns are grounded in policy as much as politics. Last year, the federal government terminated the Venezuela 2021 Temporary Protected Status designation, effective Nov. 7, 2025, ending a key layer of legal protection for many Venezuelans. Unless litigation to preserve TPS prevails, some 600,000 Venezuelans with that status will soon lose the right to work in the U.S. and could face removal.

The change has reshaped the stakes of visibility and public expression, even thousands of miles from Venezuela.

When major events unfold in a home country, the first response is often uncertainty about what comes next, said Rosamaria Cristello, executive director of the Latino Community Center of Pittsburgh. That uncertainty reaches beyond politics into questions about travel, visas and whether it feels safe to speak publicly at all.

Cristello, who is from Guatemala, said her instinct was to check in with Venezuelan staff and listen.

“The Latinx community is not a monolith, and Venezuelans’ relationship to this moment is specific,” she said. “My role right now has mainly been to listen.”

Ivan Cordoba spreads the wrinkles from a Venezuelan flags to reveal its coat of arms on Jan. 15, in their Bethel Park home. Cordoba and his wife, Maria Paparoni, do not know when or if it will be safe for them to return to visit their home country. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Ivan Cordoba spreads the wrinkles from a Venezuelan flags to reveal its coat of arms on Jan. 15, in their Bethel Park home. Cordoba and his wife, Maria Paparoni, do not know when or if it will be safe for them to return to visit their home country. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Several Venezuelans interviewed for this story said they’ve deliberately limited their news consumption, wary of being pulled into cycles of speculation and fear.

“I’m checking in the morning and at night,” said Esser. “But I can’t live in it all day.”

Esser said he still hopes to return to Venezuela someday, but not while the current power structure remains in place.

“Fear is a ghost that still haunts us. But now, there is also hope.”

Maria Paparoni

“I would never go back while the system is still there,” he said. “It’s too scary.”

At the same time, he said, he understands why Americans are uneasy about U.S. military action. “I’m relieved,” Esser said. “But I also understand why people are worried about what this could lead to.”

Paparoni described years of moments when change seemed close, dreams of the dictatorship ending, only to recede.

Still, she said, something feels different now. “Fear is a ghost that still haunts us,” Paparoni said. “But now, there is also hope.”

Asked what gives her hope, even in moments like this, Sewald-Cisnero pointed not to politics or policy, but to people.

“I believe in the resilience of humankind,” she said, while also urging community. “If you know a Venezuelan immigrant, offer them a hug. Offer presence. Offer care.”

Aakanksha Agarwal is a wine, travel and lifestyle writer from India. Formerly a Bollywood stylist, she now resides in Pittsburgh.

This story was fact-checked by Jamie Wiggan and Rich Lord.

RELATED STORIES

This story was made possible by donations to our independent, nonprofit newsroom.

Can you help us keep going with a gift?

We’re Pittsburgh’s Public Source. Since 2011, we’ve taken pride in serving our community by delivering accurate, timely, and impactful journalism — without paywalls. We believe that everyone deserves access to information about local decisions and events that affect them.

But it takes a lot of resources to produce this reporting, from compensating our staff, to the technology that brings it to you, to fact-checking every line, and much more. Reader support is crucial to our ability to keep doing this work.

If you learned something new from this story, consider supporting us with a donation today. Your donation helps ensure that everyone in Allegheny County can stay informed about issues that impact their lives. Thank you for your support!

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.