When a gangster issued the order “take him for a ride,” foot soldiers had no trouble decoding the meaning: the boss wanted them to snatch someone, kill them, and dump the body.

It’s a gruesome thought, yet rides and body dumps are a big part of Pittsburgh’s organized crime history. A trip to any Halloween fright house might pale in comparison to the surprises sprung on ordinary citizens when mobland life (and death) collided with their own.

Some of Pittsburgh’s “rides” didn’t end in murder, and the passengers lived to tell their stories to newspaper reporters and true-crime authors. Most, though, were ordinary one-way “rides” to out-of-the-way places where, oftentimes, some unfortunate person later found them. These included out-of-state mob killers, thieves, turncoats, and suspected snitches tracked to Pittsburgh, like Aaron Meyerowitz, whose killers left him in Highland Park seated in a stolen car and still holding a cigarette in his dead hand.

“The most popular method in disposing of enemies has been to ‘take him for a ride,’” wrote the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in a 1926 story about the Chicago gangland killing of prosecutor William McSwiggan. “When the ‘ride’ was resorted to, the man to be killed was invited, or forced, into an automobile, driven to the outskirts of Chicago, riddled with bullets and dumped out of the machine to the roadside.”

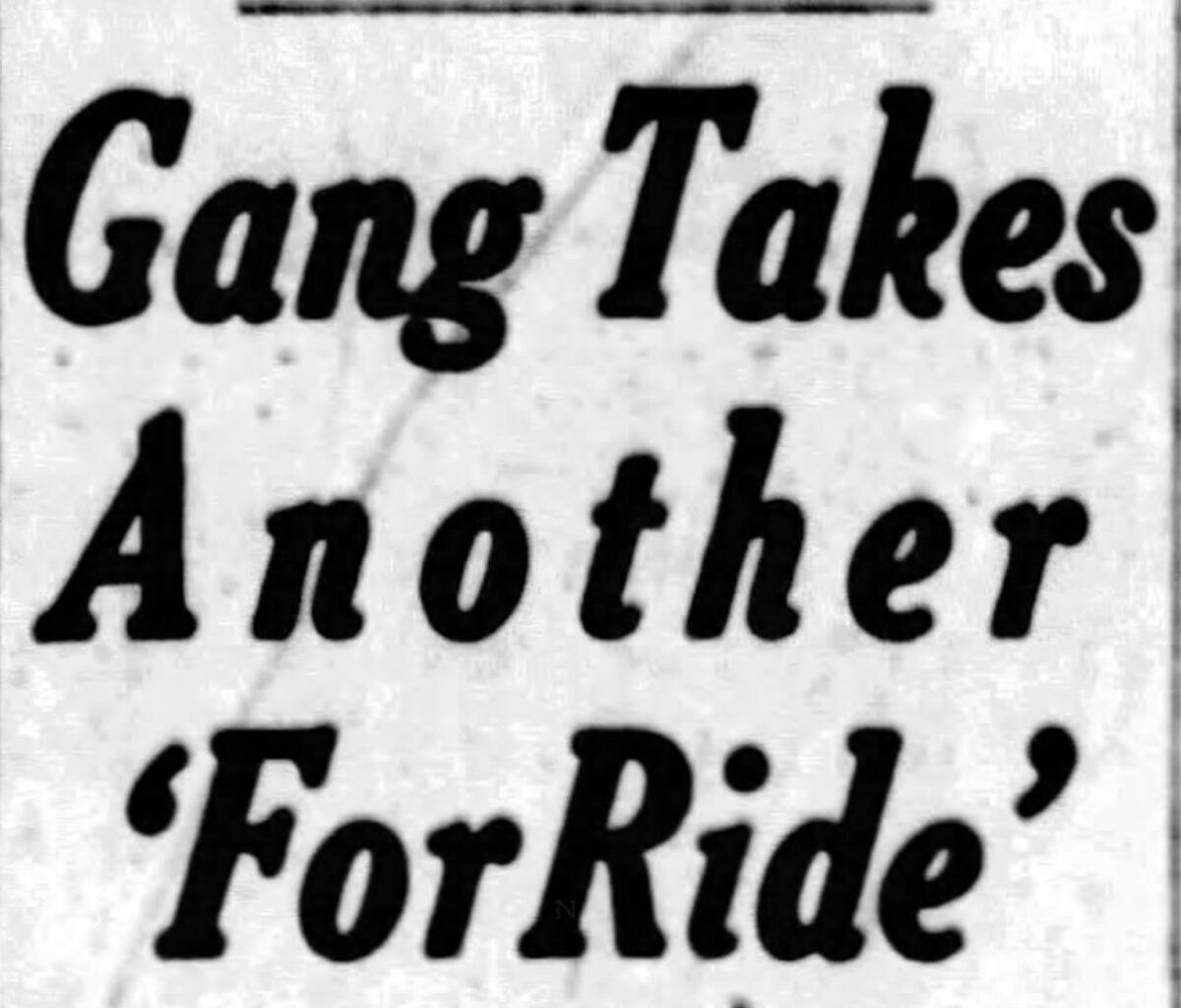

Pittsburgh newspapers began reporting on gangland rides and body dumps in 1926. One year later, local papers were reporting on Pittsburgh gangsters being taken for rides. Credit: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 29, 1926 / newspapers.com

Pittsburgh newspapers began reporting on gangland rides and body dumps in 1926. One year later, local papers were reporting on Pittsburgh gangsters being taken for rides. Credit: Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 29, 1926 / newspapers.com

Some crime historians point to Chicago as the place where rides originated in 1926, though in 1925 the Detroit Free Press reported that Nardo Nunzio had been taken for a ride and his dead body dumped. “When the [car] reached Shoemaker avenue … he was slain and his body thrown to the street,” read the article.

By 1927, the practice had quickly spread to cities throughout the United States, including Pittsburgh.

One of Pittsburgh’s earliest “rides” appears to have involved former Hill District cabaret owner and underworld figure Joseph Talamo. In September 1927, Talamo’s bullet-riddled body was found alongside a rural Washington County road. “Detectives believe those who sought to ‘get’ Talamo ‘took him for a ride,’’’ the Pittsburgh Press reported Sept. 30, 1927. A pedestrian found Talamo’s body about 30 minutes after witnesses reported hearing gunshots. “It lay beside the road in a lonely spot beyond the courthouse,” according to the Pittsburgh Press report.

Scene from the 1928 crime film classic “Lights of New York.” The movie marks the entry of “take him for a ride” into popular culture. (Warner Brothers Pictures, public domain)

Morris Kauffmann’s last ride

Morris Kauffman was a smalltime St. Louis gangster who got mixed up with the “Tri-State Gang,” an east coast robbery crew that spread mayhem and murder in cities between New York and North Carolina. Kauffman had blazed a path committing robberies armed with a Thompson submachine gun (or “Tommy gun”).

Kauffman’s last ride began March 8, 1934, with the botched robbery of a Federal Reserve Bank truck making a money pickup at Richmond, Virginia’s Broad Street Station.

Instead of stealing cash, Kauffman and three other Tri-State Gang members killed the driver and got away with worthless paper. On the run from a nationwide manhunt, Kauffman split from the gang leaders and went his own way. Known for not leaving loose ends, the gang’s leaders tracked Kauffman to the Fairfax Hotel in Oakland where Kauffman had registered under an alias: Jack Klein.

Two months after the Richmond robbery, Pittsburgh newspapers reported that Kauffman’s body had been found behind the Wendover Apartments in Squirrel Hill.

“Apparently the victim of an underworld ‘ride,’ he had been shot twice through the head,” The Pittsburgh Press reported. The paper detailed Kauffman’s wounds, which included severed fingers. Kauffman’s murder went unsolved.

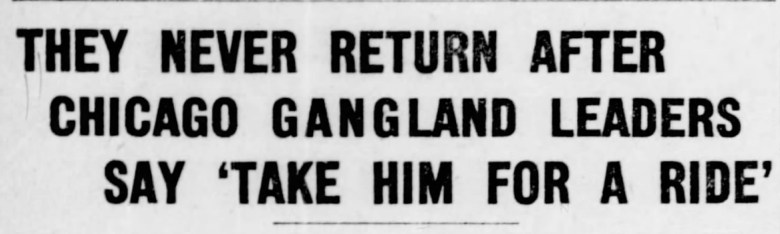

1933 FBI fugitives bulletin entry for Anthony “Tony the Stinger” Cugino. Cugino was known for taking other gangsters for rides to clean up loose ends. Cugino might have been responsible for killing Morris Kauffman in Squirrel Hill in 1934. Credit: Courtesy FBI file vault

1933 FBI fugitives bulletin entry for Anthony “Tony the Stinger” Cugino. Cugino was known for taking other gangsters for rides to clean up loose ends. Cugino might have been responsible for killing Morris Kauffman in Squirrel Hill in 1934. Credit: Courtesy FBI file vault

It’s possible that the Tri-State Gang’s enforcer, Tony “The Stinger” Cugino, tracked Kauffman to Pittsburgh and took him for a ride. Cugino was believed to have been responsible for at least 10 murders between 1920 and 1935, including the 1934 murder of a Philadelphia police officer and the accidental shooting of a Washington, D.C., newspaper deliveryman (also in 1934) during a botched assassination of a gambling kingpin.

New York City police ultimately caught up with Cugino in 1935. The gangster allegedly hanged himself in a jail cell before he could be tried.

Numbers man Mitchell Gedid’s two-way ride

In January 1953, “a gangland ride of two small-time hoodlums by the numbers mob,” the Pittsburgh Press reported, led to a sweep of Hill District numbers joints. “Six men are being sought by the County as the ‘muscle men’ who took the victims on the ride and pummeled one of them almost senseless.”

Anthony Zucco, brothers Anthony and James Mortorella, and William Gazal were bigtime Hill District numbers writers who, along with a handful of collaborators, grabbed Edward Moses and his friend Mitchell Gedid. They shoved Moses and Gedid into the back of a large black car and sped off in what newspapers at the time described as a “strange caravan which toured the city on the pre-dawn ride.”

Zucco and the others drove their victims past Leech Farm in a remote part of Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar. That’s where, in 1946, the bullet-riddled bodies of numbers men Frank Evans and Fred Garrow were discovered after they had been taken for a ride. Moses and Gedid fretted that they would end up like Evans and Garrow, whose murders remain unsolved almost 80 years later.

Before being dumped out of the car in front of his home, Gedid received a brutal beating. The captors released Moses unharmed, but with a warning. “If this punk ever tries to shake down the boss, tell him to let us know and we’ll take care of him, but good,” Moses reportedly told police after the ride.

Zucco’s son, who was 3 when the ride happened, didn’t recall hearing Moses’s name, but he did know Gedid. “He was just a guy that lived in the Hill District,” Len Zucco said in a 2019 interview. “We used to have the newspaper and story of the ride involving my father.”

The racketeer’s son who didn’t get into the family business gave his take on the 1953 ride: “They probably punched him a few times. Probably got a bloody nose,” he said. “They just beat him up. That was the law they lived by.”

The threats to stay away from the Hill District went unheeded. “Gedid apparently did not let the ride interfere with his vocation, for city police arrested him on the old, familiar charge, writing numbers,” the Press wrote about Gedid’s bust one day after the ride.

The end of the road for Danny Meyers

In February of 1946, Aaron Meyerowitz, aka Danny Meyers, made the unfortunate mistake of shooting three Newport, Ky. racketeers in front of a popular casino controlled by Cleveland gangsters. That mistake earned him a one-way ride into Highland Park.

Meyerowitz had worked in a Newport casino as a “stickman,” someone who works with women called B-girls inside casinos and bars to rob men. “He was regarded by the police in Newport, Kentucky and Cincinnati as being a small town punk and gambler,” wrote Pittsburgh homicide detective Peter A. Connor in a report on Meyerowitz’s murder.

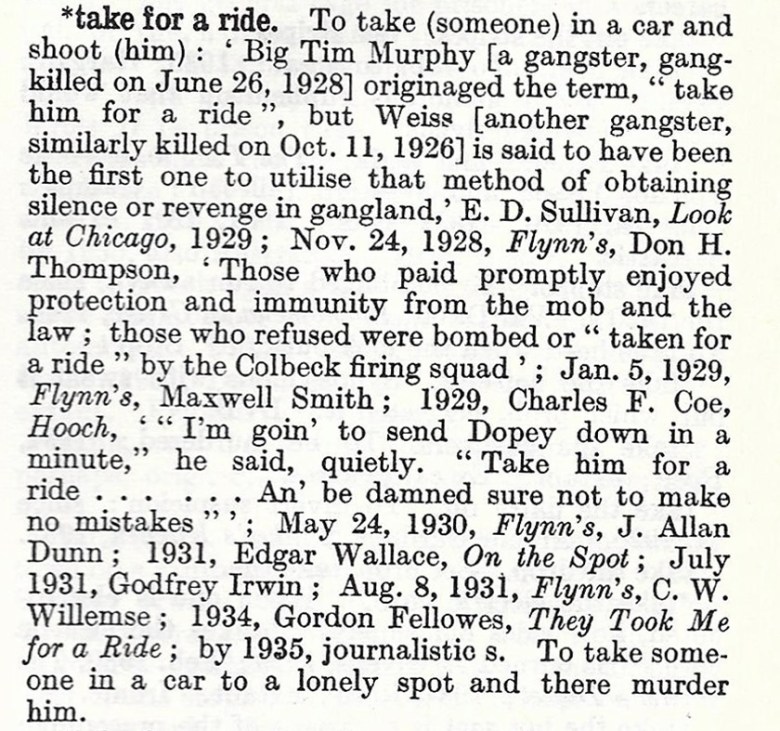

A robbery at the Yorkshire Club in Newport, Kentucky, began a sequence of events that led to Aaron Meyerowitz being taken for a ride and his dead body left in Highland Park in 1946. The casino closed long ago, but the building is still there. Credit: David S. Rotenstein. / City Paper

A robbery at the Yorkshire Club in Newport, Kentucky, began a sequence of events that led to Aaron Meyerowitz being taken for a ride and his dead body left in Highland Park in 1946. The casino closed long ago, but the building is still there. Credit: David S. Rotenstein. / City Paper

Clayton “Rip” Farley died in the shooting in the early morning hours of Feb 22, 1946, in front of the 633 Club in downtown Newport. Farley’s brother, who worked at the 633 Club where the shooting took place, and another man were wounded. A few days earlier, Rip Farley had robbed another casino one block away. That casino, the Yorkshire Club, was owned by associates of New York mob boss Meyer Lansky.

Robbing one mob-run casino while having ties to a different one was a fatal mistake. The Yorkshire owners allegedly hired Meyerowitz to send a message to the Farley brothers.

Meyerowitz allegedly fired on the Farleys with a sawed-off shotgun from a moving car. Taylor Farley survived. “Taylor Farley recognized [Meyerowitz] alias Meyers as being one of the trigger men who killed his brother and wounded him,” Connor reported.

The payback was swift. Pittsburgh police believe Meyerowitz died late the night of Feb. 24, 1946. Snow had fallen soon after the murder, and police did not observe tire tracks in the fresh snow. At 11:30 the following morning, a passing motorist approached the car and found Meyerowitz dead inside.

“The victim apparently was shot to death … as he sat beside the driver in the front of the auto,” the Post-Gazette reported in 1946. “His assailants sent two bullets from a .38 caliber pistol into the back of his head as he sat smoking a cigarette.”

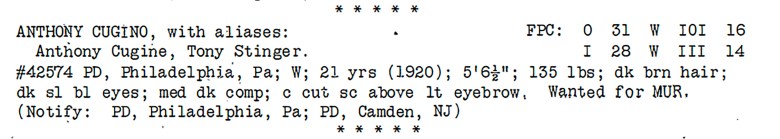

Entry in the 1949 Dictionary of the Underworld for “take for a ride.”

Entry in the 1949 Dictionary of the Underworld for “take for a ride.”

Speculation swirled in the aftermath of the shooting. Was it payback for the Yorkshire Club robbery or something else? The Farley’s had come to Northern Kentucky from Clay County, historically a hotbed of violent feuds. “Mountain vengeance or the double-cross blamed in slaying,” read the Pittsburgh Press headline Feb. 26, 1946.

Meyerowitz’s murder remains unsolved. He died ignominiously for breaking a gangster’s code that meted out harsh consequences for infractions.

The gangster’s code, the “law they lived by,” was unforgiving. In the underworld where a ride was a lot more than transportation from one place to another, a gangster could be judged by his captors in one block, and a death sentence carried out in the next.

This article appears in Oct. 22-28, 2025.

RELATED