Western State Penitentiary. Riverside Intermediate Prison of Western Pennsylvania. State Correctional Institution at Pittsburgh. Riverside Community Corrections Center. The Wall.

The prison that sits along the Ohio River north of the Chateau neighborhood has gone by so many names and phases of reconstruction that you’d be hard-pressed to find a Pittsburgher who knows that the narrow, castle-esque structure that stands there today isn’t the first local penitentiary to be colloquially known as “Western Pen.”

At the end of August, local historian Doug MacGregor independently published “Western State Penitentiary / SCI Pittsburgh: A History” — a book that spans the nearly 200-year history of the two structures and connects it to the limbo in which it sits today.

The Pennsylvania Department of General Services, which has been the site’s manager since the Department of Corrections relinquished it to them in 2017, has the current Western Pen facility slated for demolition in 2026. The original penitentiary was completed in 1827.

MacGregor worked at the prison in 2014. In his book’s introduction and in conversation with NEXTpittsburgh, he says he wrote the book he wanted to read.

“When I first got there, it was a fully active prison, but it’s also, again, a very historic structure,” he says. “I started looking around, like, ‘I want to read more about this place,’ and there just wasn’t anything out there.”

In 2016, MacGregor published a brief history on his personal website — a year before the prison would close for the final time.

“But then, after they shut the place down, I was like, ‘Well, I need to write the whole history of this place.’”

Failing upward

Arguably the most critical piece to Western Pen’s existence is the Pennsylvania System of Penology: A puritanical reformation method that locked inmates in solitary cells to contemplate their sins. The term “Penitentiary” is rooted in the word “penitence.”

“You just sit in that room for how many years you got sentenced to, and you don’t come out until you’re better,” MacGregor says.

Solitary confinement as a means of reformation — even though the method is now considered crude and malignant — arose after the Revolutionary War at the end of the 18th century. Previous to it, serving justice for a crime was more of a spectacle that involved fines or other types of punishment, MacGregor says.

Pennsylvania wasn’t the first locale to have a penitentiary, but it was the first built for the Pennsylvania System, which was thought to be the ideal form of incarceration at the time.

Completed in 1827, the “first” Western Pen cost somewhere between $165,000 and $179,000 — about $4.2 to $4.5 million today. The octagonal building featured a central, cylindrical core of cells rather than the long, narrow halls of them that would become commonplace in the future.

In his book, MacGregor writes that it was “the best example that has ever existed of the solitary system carried to the most vicious extreme.”

But the system that stimulated its construction proved its biggest shortcoming.

“That system wasn’t sustainable,” MacGregor says. “Not only is it inhumane, it cost a lot of money. A single cell for every single prisoner and they don’t do anything?”

A colorized version of the 1839 sketch titled “Penitentiary near Pittsburgh,” by illustrator Karl Bodmer. The image depicts the original Western State Penitentiary, which was completed in 1827. Image courtesy of DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University via flickr.

A colorized version of the 1839 sketch titled “Penitentiary near Pittsburgh,” by illustrator Karl Bodmer. The image depicts the original Western State Penitentiary, which was completed in 1827. Image courtesy of DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University via flickr.

At the time, the building itself had a host of issues, from inadequate water flow for sanitation to poor visibility for guards and the complete lack of an infirmary. There wasn’t much government funding to support improvements to the facility, and without a system in place to make money, Western Pen was struggling.

On the other side of the state, Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary was quietly learning from Pittsburgh’s mistakes. It opened only two years after Western Pen, in 1829, but shirked some of the Pennsylvania System’s archaic directives to include something profitable: Prison labor.

By 1833, Western Pen entered another period of construction that would see it modified to reflect Eastern Pen. The central core of cells was demolished to make room for two wings of cells that fanned out like a “V.” It would host a total of 180 cells.

By 1837, they were complete, but this version of Western Pen would remain in perpetual construction for a host of improvements — including a third wing of cells — until 1872.

MacGregor quotes penology historian Harry Barnes’ “The Evolution of Penology in Pennsylvania” in his book: “Few prison structures have had so short and unsuccessful an existence as Western Penitentiary in its original form.”

Getting to work

MacGregor calls prison labor at these penitentiaries a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it was exploitative. Inmates were made to work for little to no pay with no recourse.

At the same time, MacGregor says, “it gave these guys a break.”

“Think about being locked in a room 23 hours a day with no light. You’re going to go crazy. They’re begging for something to do.”

Until the “success” of prison labor at Eastern State, the Pennsylvania Legislature and Philadelphia Society had refused to deviate from the isolation-based Pennsylvania System, even though both organizations knew “early on that solitary confinement led to illness,” MacGregor writes in his book.

After a visit to Western Pen in 1842, Charles Dickens wrote that inmates would scream for work, lest they “go raving mad,” merely in response to the trap in their cell door being opened.

“He has it; and by fits and starts applies himself to labour; but every now and then there comes upon him a burning sense of the years that must be wasted in that stone coffin, and an agony so piercing in the recollection of those who are hidden from his view and knowledge, that he starts from his seat, and striding up and down the narrow room with both hands clasped on his uplifted head, hears spirits tempting him to beat his brains out on the wall,” Dickens writes.

MacGregor says that shoes were a popular product to be made in prisons. During labor’s introductory period, each inmate worked in solitude, but by the 1860s, penitentiary officials realized they could increase production if inmates worked together and formed production lines of sorts.

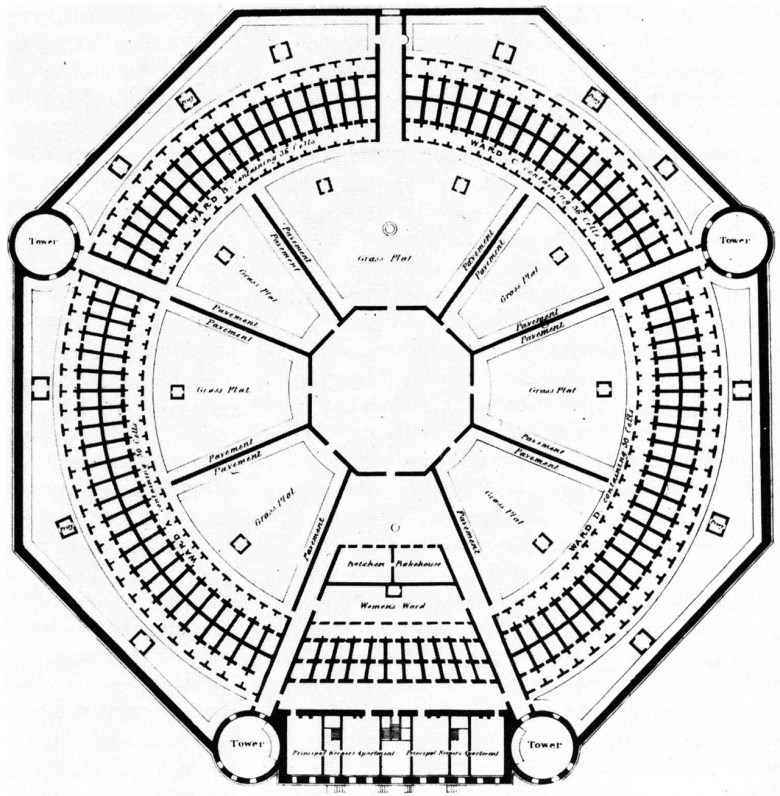

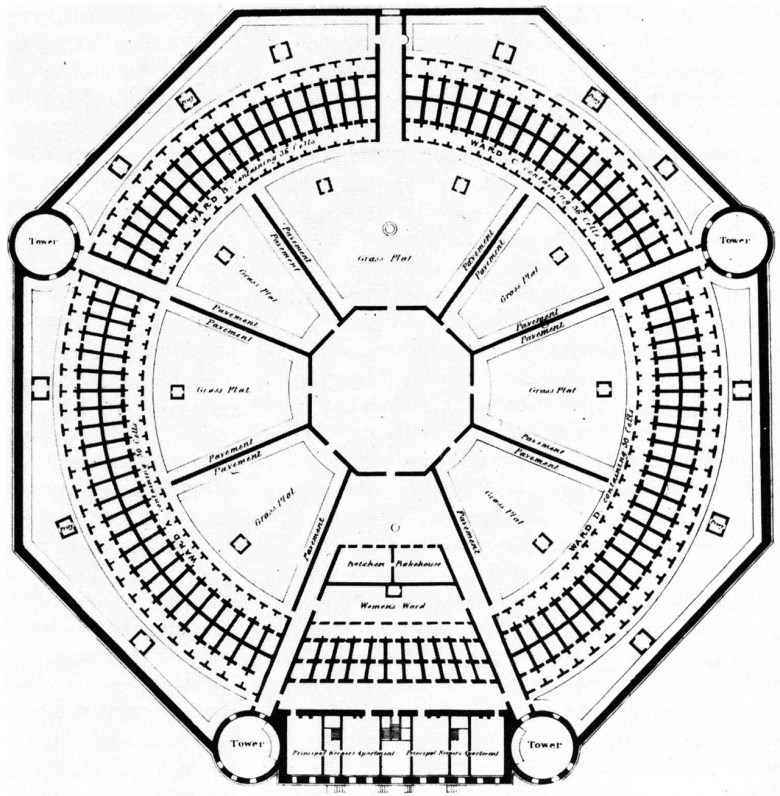

A floor plan for Western State Penitentiary’s original construction. Image originally published in William Crawford’s “Report on the Penitentiaries of the United States,” courtesy of Doug MacGregor.

A floor plan for Western State Penitentiary’s original construction. Image originally published in William Crawford’s “Report on the Penitentiaries of the United States,” courtesy of Doug MacGregor.

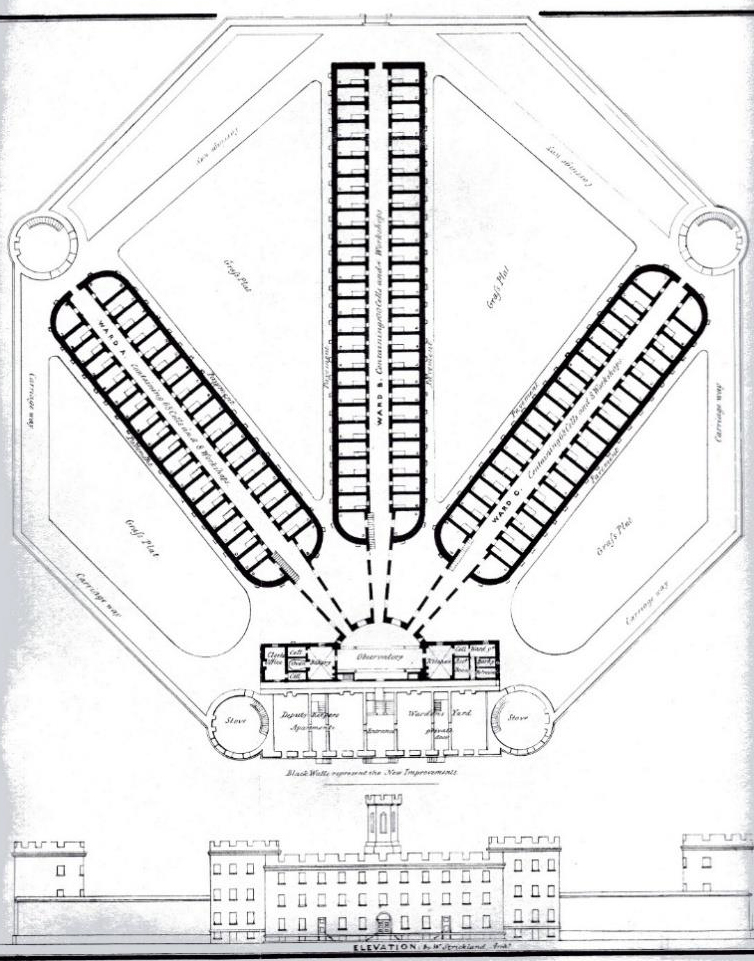

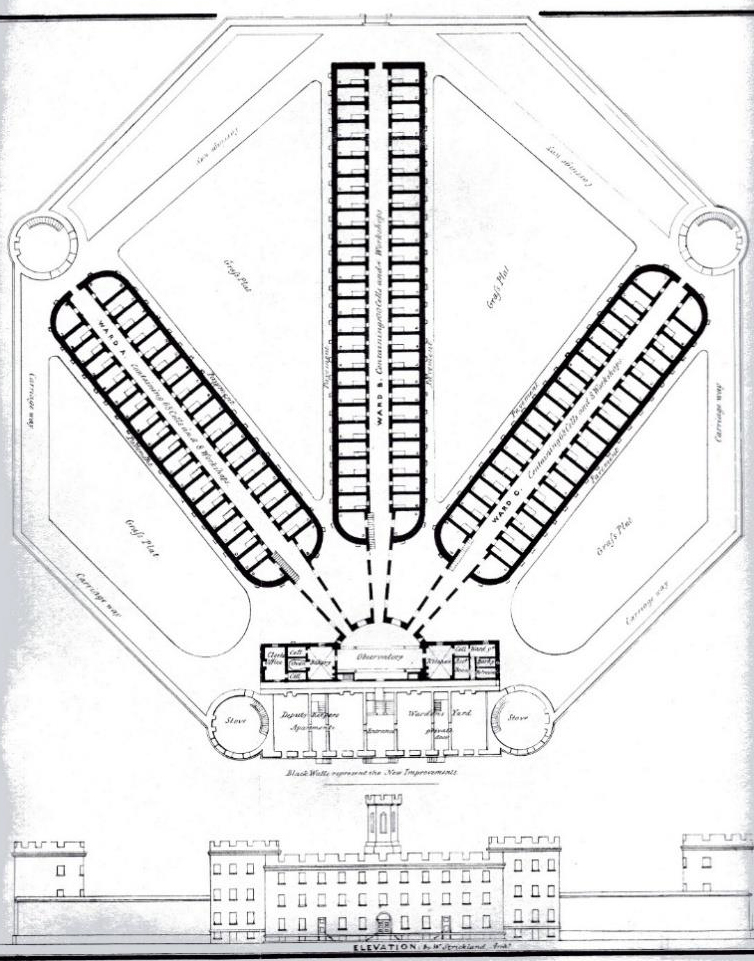

Western Pen’s updated floor plan after Eastern State Penitentiary proved the design’s success. Image originally published in William Crawford’s “Report on the Penitentiaries of the United States,” courtesy of Doug MacGregor.

Western Pen’s updated floor plan after Eastern State Penitentiary proved the design’s success. Image originally published in William Crawford’s “Report on the Penitentiaries of the United States,” courtesy of Doug MacGregor.

Regarding coerced labor in the prison: It is worth remembering that during this time in American history, slavery was still occurring and wouldn’t be abolished nationally until 1865.

Until that point, there weren’t many Black Pittsburghers. MacGregor’s book notes that only about 1/35th of the region’s population was Black in 1835, but one-third of Western Pen’s inmate population was Black.

This disproportionate rate of incarceration was also present at Eastern State Penitentiary. Since becoming a museum, Eastern Pen has continuously called attention to that disparity and used it to start conversations about racial injustice in the American justice system.

Although Pennsylvania did not permit slavery, the unbalanced population figures and associated labor show a gruesome similarity. Comparisons between prison labor and slavery persist to this day.

From the perspective of penitentiary leaders, though, it was a success: Labor generated profits while also teaching inmates a trade, which they assumed would increase their chances of rejoining the workforce upon release.

Still, they saw one major hurdle as hurting production speed: a lack of space.

‘The model prison for the nation and the world‘

By the mid-1870s, Western Pen had space for 500 inmates but was holding 830. The continuous additions to the building over the decades limited space for labor.

To resolve both issues, prison officials decided to construct the Riverside Intermediate Prison of Western Pennsylvania. The additional space would host nonviolent, first-time offenders under 30 years old, and would prioritize reforming these younger inmates to rejoin the general population with workforce skills.

But the plan faced opposition from the leaders of Allegheny City — now known as Pittsburgh’s North Side. According to MacGregor’s book, the leaders wanted Western Pen to be eliminated and demolished, not expanded in any capacity. One primary reason cited for the push was escape attempts, since Allegheny City would essentially be a first stop for escaped inmates based on its location.

The issue of prison overcrowding won out against the complaints, though, and construction began in 1879. It continued sporadically for the next 17 years.

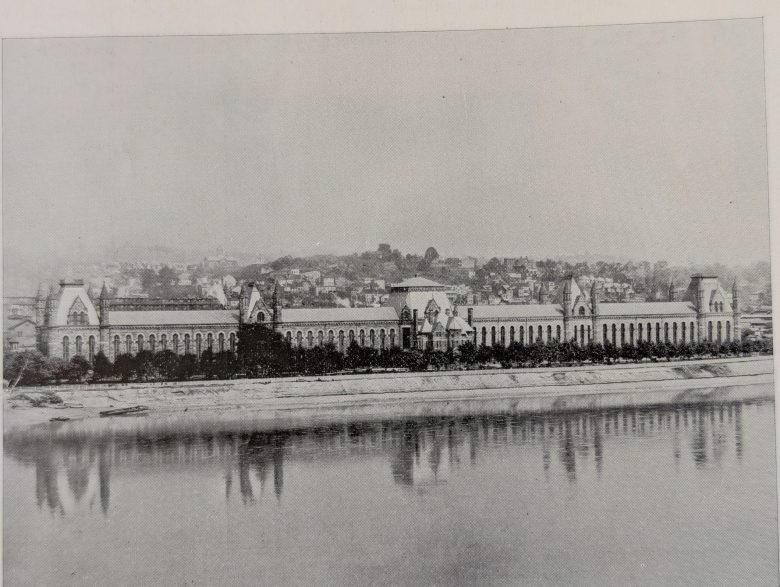

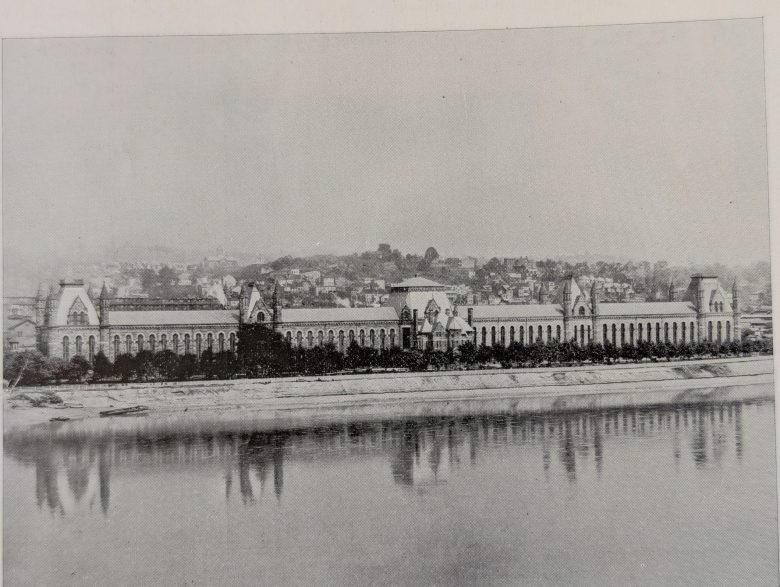

A photo of he Riverside Intermediate Prison of Western Pennsylvania from 1897. Image originally published in “City of Allegheny, PA: History and Institutions,” courtesy of Doug MacGregor.

A photo of he Riverside Intermediate Prison of Western Pennsylvania from 1897. Image originally published in “City of Allegheny, PA: History and Institutions,” courtesy of Doug MacGregor.

Allegheny City leaders’ wish to eliminate Western Pen technically came true as well, but not in the way they wanted.

Come 1884, Western Pen officials had decided Riverside was the superior facility and would solely operate out of it. The final inmates of the original Western Pen were transferred to Riverside in May 1884. Less than a year later, during the summer of 1885, the old penitentiary was razed.

Around the same time, Pittsburgh was seeing an influx of Black residents from southern states who were moving north to escape Jim Crow laws.

“Although the number of Black Pittsburghers remained low through much of the 19th century, by the 1890s those numbers grew exponentially,” MacGregor’s book reads.

Disproportionate rates of incarceration persisted. In 1890, there were about 10,000 Black Pittsburghers compared to the city’s total population of 238,617. That would rise to about 40,000 by 1930, amid a total population of 669,817. That means about 4% of Pittsburgh’s population was Black in 1890, and nearly 6% in 1930.

“[State] inspectors noted that although the Black population was only 10.52% of inmates in 1894, it had grown to almost 20% in 1898,” MacGregor’s book reads. “That pattern of growth would continue over the years.”

MacGregor’s book nods to the fact that during this era of segregation, Pittsburgh leaders made mention of providing funding for more Black schools, employment opportunities and other amenities, but those funds and resources never materialized.

Amid it all, the penitentiary grew.

By the 1890s, the Riverside facility — the new Western Pen — had workshops, a chapel and about 1,200 cells. That was just the north wing; within the next 30 years, a south wing would be added. The final cost for the site was more than $2 million — nearly $38 million today.

MacGregor quotes the historian Barnes once more: He calls Riverside, “the most expensive and pretentious building which had yet been erected in America.”

During this nearly 100-year period, ongoing construction and increased inmate access to other parts of the facilities provided ample opportunities for escape attempts, but the penitentiary’s perceived successes overshadowed these occasional stains.

“From the 1870s to 1897, that is the pinnacle of Western Penitentiary,” MacGregor says. “We are, really, the model prison for the nation and the world.”

This article is the first in a series about Western Penitentiary. Future installments will explore the prison’s evolution into State Correctional Institution Pittsburgh, subsequent closure and the fight for its future. This postscript will be updated to include links to those articles.