Chris Winslow, a Great Lakes specialist and researcher at Ohio State University, gave a Lake Erie status update at the City Club on Thursday. It was reminder that accurate monitoring of the world’s largest fresh water supply need to be kept strong in an era of federal cuts to scientific research. Credit: Mark Oprea There is a special mirage that we all acknowledge about Lake Erie.

Chris Winslow, a Great Lakes specialist and researcher at Ohio State University, gave a Lake Erie status update at the City Club on Thursday. It was reminder that accurate monitoring of the world’s largest fresh water supply need to be kept strong in an era of federal cuts to scientific research. Credit: Mark Oprea There is a special mirage that we all acknowledge about Lake Erie.

Beneath that seemingly endless pool of blue and grey is a whole heap of problems. There’s the algal blooms. The invasive fish and the microscopic pollutants.

But all of that must be acknowledged to keep Lake Erie, and its four siblings, healthy and a Midwestern landmark, Chris Winslow, a Great Lakes specialist and researcher at Ohio State University, said at a City Club lecture on Thursday.

“This is a Great Lake,” Winslow said. “Not a very good lake.”

The talk, titled “The State of the Great Lakes,” was hosted in the middle of what could be a trying time for city, county and regional limnologists fixated on maintaining Lake Erie’s current quality in midst of federal indecision.

The Trump administration, in a May executive order, promised to shield the Great Lakes from the threat of Asian carp by boosting a popular inter-basin construction in Illinois. But the White House has also mulled over cuts to programs used in previous administrations to tackle pollution and bolster wetlands meant to keep a huge stock of the world’s fresh water, well, fresh.

Which means, in Winslow’s mind, a substantial need for cities and towns nestled along Lake Erie to work collaboratively to do the clean-up work without leaning too much on the Feds.

“You cannot manage what we don’t measure, right?” Winslow told the room. “If we are the stewards of this lake, all five Great Lakes—you can’t manage that resource unless you monitor it and you understand the science that’s out there, okay?”

“So, we are not done monitoring,” he said.

And monitor Winslow does. Whether that be the migratory patterns and population of Asian carp, or the nutrients that fuel algal blooms, or the excess phosphorus that leads to low-oxygen “dead zones” in Lake Erie, or the who-knows-how-much amount of microplastics in the water.

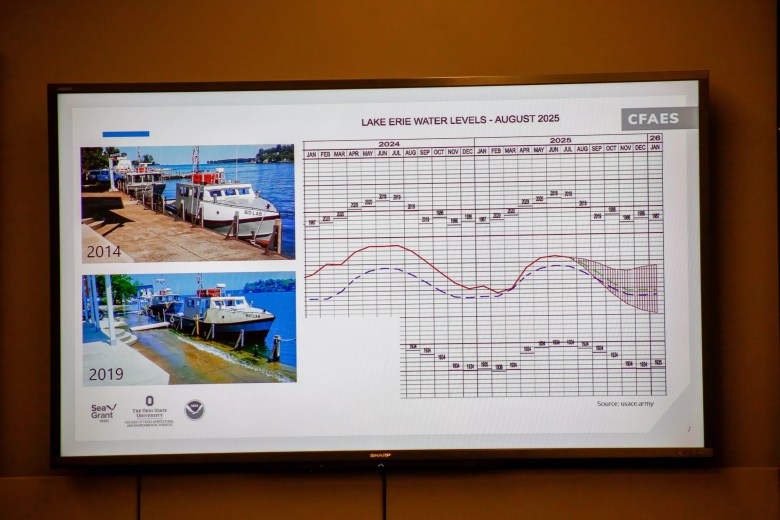

The State of the Great Lakes: water levels are increasing. Credit: Mark Oprea Or even conundrums that involve an overlapping network of entities including the Port Authority, the Great Lakes Water Alliance, the Metroparks and the City Planning Commission. How do lakeside governments manage rising water levels? (Which are rising.) What do we do with all of Lake Erie’s 1.5 million pounds of lakebed earth dug up each year?

The State of the Great Lakes: water levels are increasing. Credit: Mark Oprea Or even conundrums that involve an overlapping network of entities including the Port Authority, the Great Lakes Water Alliance, the Metroparks and the City Planning Commission. How do lakeside governments manage rising water levels? (Which are rising.) What do we do with all of Lake Erie’s 1.5 million pounds of lakebed earth dug up each year?

“Can we grow crops on that? Can we move that sediment back onto our agricultural fields? Can we construct mountains?” Winslow said, hinting at the routine dredging carried out by the Port. “Can we actually harvest that sediment and sell it on the market, or build construction material?”

And for Lake Erie, it’s a battle between more and less. More heat, more algae, more walleye to fish, more “slimy biofilm” left on trashed plastics—those that contain faint amounts of antidepressants and caffeine that linger around Lake Erie. “A way to dose ourselves,” Winslow said.

And, of course, all up against less funding.

County Executive Chris Ronayne, who segued his love for Lake Erie last year into the county’s PSA-friendly Fresh Water Institute, became head of the of the Great Lakes Regional Forum earlier this month, which could mean more dollars from Cleveland, Chicago and Detroit tossed into water upkeep.

Or at least trying to maintain the principles of the the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, a Nixon-era contract between the U.S. and Canada that keeps each country in check as far as pollution and harmful species go. (Or rivers catching on fire, for that matter.)

But Winslow, being one of Ohio’s chief academics obsessed with everything Lake Erie, stressed on Thursday that updated data precedes any future agreement or, say, taxpayer money thrown at another research buoy.

“There is no difference between a healthy environment and a healthy economy,” Winslow said.

“As long as we keep that in mind,” he said, “any investment in the protection and restoration of this lake will pay itself back for us.”

Related

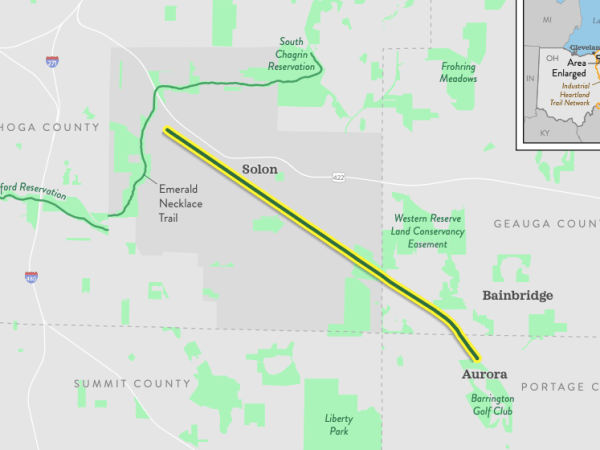

Mayor Ed Kraus needs to raise $2 million to secure, by summer’s end, seven miles of track line from Northfolk Southern

Subscribe to Cleveland Scene newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

Related Stories

As the Haslams push for a dome in Brook Park, Scene has obtained a rendering of the much talked about but never publicly seen plan B, which remains a real possibility

Mayor Ed Kraus needs to raise $2 million to secure, by summer’s end, seven miles of track line from Northfolk Southern

This article appears in Cleveland SCENE 10/8/25.

Related