Winter winds and snows howled across America in 1888. The far west had undergone the first blast in January. And other storms were not far behind. But the touring acting company of Madame Helena Modjeska (1840-1907), one of the most popular stage stars of the day, was not to be put off.

Helena Modjeska portrait by Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz, 1880

The 1887-1888 tour was the 11th since the Polish born actress had begun them in the late 1870s and was to encompass 68 cities and towns. All that January and February of 1888 her private railroad car traveled from Lawrence, Kansas, and St. Joseph, Missouri, down south and on to the upper Midwest. It entered Pennsylvania at Erie, and up to New York. A brief stop across the border to Toronto was followed by several days in New York City.

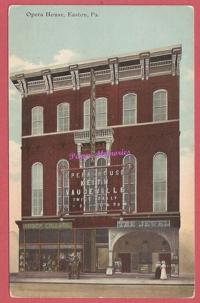

By the start of March 1888, Modjeska and her troupe of actors had arrived at Easton. They had appeared here once before. The site of the performance was to be the Abel Opera House, a local show place built in 1872 by Edward Abel (1831-1913). Brought up on a Forks Township farm, Abel went to South Easton where he worked in a country store. Eventually, with several partners he ran a successful carpet business.

Many years later Abel explained, writing in the third person, what was behind his vision: “Public spirit is what led Mr. Edward Abel to build the opera house, to give the public a suitable place for the assembling of the people, and for amusements. By doing so Mr. Edward Abel sacrificed his private fortune.”

Abel Opera House, Easton

Cinema Treasures

After several fires in the 1920s it was converted into the Embassy movie theater. The space is now the Sigal Museum, home of The Northampton County Historical and Genealogical Society.

The arrival of Modjeska’s private railroad car the “Newport” (named after the southern California town where Modjeska was based) on March 9 from Scranton had created a stir in Easton, as it did everywhere she went. Apparently, several other cars for the rest of her cast were added.

Her play of choice for Easton was Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night,” which she had done in Scranton and was scheduled to be repeated in Allentown.

Modjeska specialized in Shakespeare. According to the book “Starring Madame Modjeska: On Tour in Poland and America,” by Beth Holmgren, Modjeska wrote a letter in 1899 to Dr. Clarke of Louisville Kentucky, in reply to a book on medical themes in the Bard he had sent her, where she recalled her early attraction to the great English playwright:

“I shall never forget when a girl of 15 I took hold of “Hamlet” a Polish translation… not bring able to purchase it I copied the whole play and carried it a rare treasure, studying the scenes of Hamlet and Ophelia all in great secret. How much more I adored him when I read his plays with a matured mind!”

Modjeska’s roots were humble ones. She was born Jadwiga Benda in 1840 in the ancient Polish city of Krakow. Her family had been middle class. Her mother was a widow who had lost valuable property in a tragic fire that swept the city in July 1850. All that was left for her was to run a small café.

“Her mother Jozefa Misel Benda was the widowed head of the household when Helena was born, and the mother of sons Jozefa, Szmon and Feliks,” Holmgren writes. “She was baptized as Helena Opid, and Michal Opid married her mother after her birth. Modjeska later acknowledged him as her father.”

Later Modjeska married a 25-year-old stage actor named Gustow Zimajar, whose stage name was Modjeska, the name she later adopted. They had a son Rudolf, later Ralph, and daughter Maria. The daughter died young, but Modjeska’s son later became one of America’s leading bridge engineers, with Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin bridge and San Francisco’s Bay Bridge to his credit.

Eventually Modjeska’s career on the stage began to rise. Discovering Zimajar was poorly managing her and secretly married to another woman, she left him and married Karl Bozenta Chlapowski, a member of Polish aristocracy who had an interest in the theater and eventually became the editor of a leading newspaper. What followed was a career that after eight years took her to the Warsaw Imperial Theatres.

Scholars Johanna and Catharina Polatynska suspect Modjeska might have been the model/inspiration for the character of Irene Adler, the opera diva and “adventuress” that outsmarted Sherlock Holmes in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective tale “A Scandal in Bohemia.”

By 1876 Modjeska was ready to start on an international career. America would be the place. Although the country was in an economic downturn, Modjeska and her husband felt they had little future in a Poland occupied by the Russian, Austrian and German empires. They talked of establishing a Polish artist colony in the New World.

After visiting Philadelphia and New York, both of which they found overcrowded and unsuitable, they sailed to the West Coast. Modjeska was attracted to San Francisco, especially by its large émigré Polish population. But eventually they moved to southern California around Anaheim. It was impossible to keep Modjeska away from the stage too long. She wondered if she could handle the Bard in English. Besides they needed the money.

At that time many towns, big and small, had a stage theater of some sort. It was in many cases their sole source of entertainment. They were always looking for plays and actors to appear. Modjeska offered it to them.

There are apparently no surviving accounts of Modjeska’s appearance in “Twelfth Night” in Easton. But one from the Ann Arbor Michigan Register of January 12, 1888, just two months before had this to say:

“Twelfth Night is a comedy which leaves a rich flavor when it is presented well, and it was presented well in Ann Arbor Tuesday evening. Modjeska, as Viola was perfect grace, and carried the sympathy of the audience completely, especially in the exquisite passage in which the heroine in disguise as a boy tells of her love for the Count and of the superior love of woman. Modjeska evidently cares so much about her art that she will not tolerate poor actors about her.” The review went on to praise by name the rest of the cast who appeared with her.

The performance in Easton ended, and the cast moved on to Allentown. Modjeska had had been scheduled to appear at the Academy of Music on October 8, 1883, but the show was cancelled due to illness. This was to be her first appearance there.

1891 photograph of the Academy of Music at the northeast corner of Sixth and Linden Streets. The building was destroyed in a fire in 1903.

Lehigh County Historical Society

On March 10, 1888, those Allentown citizens that picked up their copy of the Chronicle and News would have read the following weather forecast: “The indications for today are light to variable winds shifting easterly; warmer fair weather.” When the afternoon shifted to rain at shortly before 6:00 no one had any reason to suspect more than that.

It is only at 10:00, as the Academy of Music crowd was letting out from “Twelfth Night,” that they realized snow was falling. The horse-powered streetcar line had stopped running and those without carriages were compelled to walk. As they had a performance scheduled for the next evening in Lancaster, Modjeska’s cast had to get there early the next day.

From scattered newspaper accounts, we can gather that Modjeska’s train had no real trouble leaving the city but, in the country, it was a different story. Piles of snow had train service snarled beyond anything that was seen before and many old timers recalled that not since the Great Storm of 1830 had that much snow fallen.

Modjeska was not happy. The Chronicle and News contained stories of her infuriated shouting in two languages and banging her foot on the Newport’s floor as she urged them to dig deeper and get the train moving.

Modjeska and her actors finally arrived in Lancaster, but that night’s performance had to be cancelled. In fact, it was not until March 13 that they would appear in the Fulton Street Opera House to perform “As You Like It.” Modjeska was not going to let the blizzard keep her from performing. But it is interesting that although she continued to perform until 1907, she apparently never appeared in Allentown again.

In 1893 Modjeska her husband and her son became naturalized U.S. citizens. She died at Newport Beach, California on April 8. 1909. Her ashes were later interred in Krakow’s Rakowicki Cemetery.

In 1888 Modjeska and her husband purchased a home and garden in Orange County, California and gave it the name the Forest of Arden, taken from one of Shakespeare’s plays. Designed by a young architect named Stanford White, both house and gardens are open to the public.