State lawmakers held a hearing Tuesday on a set of bills intended to reduce burdens on students and families involved in Pennsylvania’s juvenile court system.

The three-part package would require judges to refer some students to diversion programs instead of detention, limit the number of days students can be held pre-trial, and eliminate most fines and fees from the juvenile court system.

“Children should not be propping up our criminal justice system with the money that they have to pay into it,” said Allegheny County representative Emily Kinkead, who introduced the bill to eliminate fines and fees. “They should not be paying for their own incarceration, for their own supervision.”

If enacted, Pennsylvania would join 24 other states across the country that have already eliminated all or some fines and fees from the juvenile justice system, according to a report from the Juvenile Law Center published this week.

Unpaid fines were the most frequently alleged offense in 2021, according to the state’s Juvenile Court Judges’ Commission (JCJC). Black youth are most likely to end up with long-term consequences for that offense.

Bob Tomassini, executive director of JCJC, voiced his support for eliminating fines and fees outside of those related to restitution and victim compensation. He also stressed that the commission supports diversion “whenever appropriate, with decisions that are based on each youth’s unique circumstances.”

But Tomassini raised concerns about several other provisions included in the bills, such as those that would raise the minimum age for juvenile court involvement from ages 10 to 13 and count the time youth spend in detention awaiting trial toward their total sentence.

He also cautioned lawmakers against limiting judicial discretion. The diversion bill, introduced by Philadelphia-area representative Rick Krajewski, would require juvenile court judges to offer community service or other diversion-based options to any student with fewer than three prior misdemeanor charges.

Donald Corry, president of the Pennsylvania Council of Chief Juvenile Probation Officers, said that while diversion is a core part of the juvenile justice system, each decision made in juvenile cases requires “discretion and balance.”

“The decision of when [diversion] is appropriate is not automatic,” Corry said. “It requires careful consideration of many factors within the framework of Pennsylvania’s juvenile justice system.”

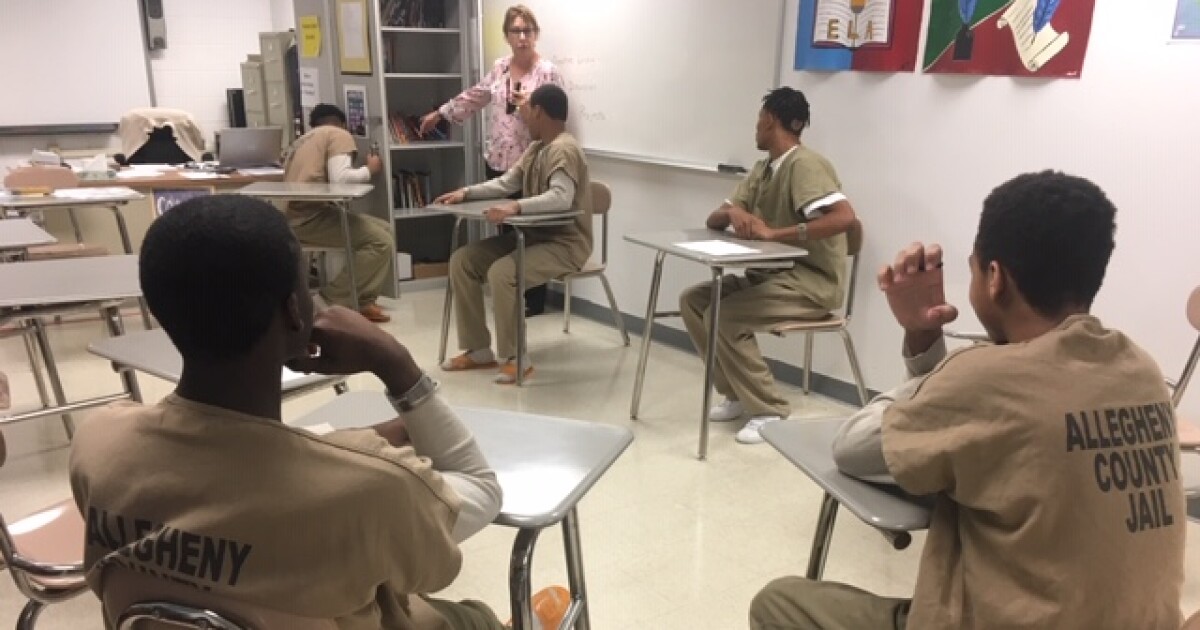

But Krajewski countered that his bill leaves it up to judges and their communities to decide what a diversion program should look like. Diversion programs in Allegheny County range from community service and academic tutoring to career readiness coaching and whole-family support.

Nationally, these programs have been found to be more effective than punitive criminal justice approaches — such as fines and jail time — in reducing the chance youth will backslide.

A citywide youth diversion program in Philadelphia has led to an 91% decrease in school-based arrests since 2014 and a 34% reduction in serious behavioral incidents. Diverted students in that program also were less likely to face future exclusionary discipline, such as suspensions and expulsions.

“We’re just saying let’s have some guidance so that a youth who offends in Philadelphia County can have the same opportunities as youth in Cambria County or Cumberland County to be able to not get institutionalized and have a pathway out of the system,” Krajewski said.

For 22-year-old Christina Zogar, the reforms to limit detention for youth awaiting trial are personal. At 16, Zogar was held for two years at the Juvenile Justice Service Center in Philadelphia before she was sentenced and transferred to a juvenile detention center in the middle of the state. She served two more years there.

The time she spent detained in Philadelphia did not count toward her total time served. Zogar told lawmakers that she often wonders what she could have accomplished if the court system had taken the two years she sat awaiting sentencing into account.

“My community wasn’t safer by me coming home at 21 than it would’ve been for me coming at 19,” Zogar told lawmakers. “I did everything in my ability to change and grow, yet none of my growth was recognized.”

All three bills are based on recommendations made by the state’s bipartisan Juvenile Justice Task Force in 2021. An earlier version of the legislation was introduced in 2023.