The right to teach, debate and protest faces a high-stakes challenge in Pittsburgh’s universities and beyond.

When the inaugural Pennsylvania Energy and Innovation Summit was held at Carnegie Mellon University in July, the CMU College Democrats wanted to hold an on-campus protest. Club leaders braced themselves for the red tape that now comes with registering such an event at the university. But officials were quick with a decision: The protest couldn’t take place, because the school didn’t have enough university police available to ensure safety.

So instead, students joined off-campus protests, something that introduced “a lot of outside factors,” according to River Sepinuck, vice president of the club.

“One of those factors being external police forces,” he said. “Some students ended up getting pepper-sprayed,” which he felt wouldn’t have occurred if a protest was allowed on campus.

Irritant spray was used on July 15 at a protest following the inaugural Pennsylvania Energy and Innovation Summit. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Irritant spray was used on July 15 at a protest following the inaugural Pennsylvania Energy and Innovation Summit. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Protesters and police clashed after the summit, at which President Donald Trump was the keynote speaker. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Protesters and police clashed after the summit, at which President Donald Trump was the keynote speaker. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Campus members told Public Source that’s the only time, so far, that they’ve seen an “expressive activity” event rejected under year-old procedures mandating registration for gatherings (like protests) expected to have 50 or more participants

Students and faculty wonder if the policy’s existence has chilled campus speech and expression — even on time-honored forums such as The Fence. The university is one of several schools that put new rules in place following nationwide pro-Palestinian protests that roiled colleges in spring 2024.

What does CMU’s scheduling of expressive activity policy say?

CMU “may impose reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on the exercise of speech.”

Scheduling is required for events where 50 or more people are expected (originally 25 people before campus feedback led to an increase in June).

Any urgency to hold an event should be “viewed in the context” of safety and university operations.

Sponsors “partner with the university in planning, scheduling and conducting the event.”

Student Affairs meets with the sponsor.

University police may be consulted.

If any non-university people are involved, “the sponsoring organization is responsible for security costs.”

No publicity should occur until the university has approved the event.

Source: CMU’s website

Higher education and free speech organizations condemned the policies, with the American Association of University Professors calling them “overly restrictive” and alarming. Some CMU students and faculty say it’s made organizing on campus difficult and wonder if it’s been selectively enforced.

The CMU Democrats haven’t held or attempted to hold what would qualify as an expressive activity since the summer.

“We’ve been avoiding making large events specifically because the policy creates these massive cost barriers, all these hoops you have to jump through,” Sepinuck said. “It makes it kind of prohibitive to [hold] large expressive events.”

A partisan debate? That’s $1,000

In April 2024, the University of Pittsburgh’s campus joined others around the country with protests and encampments calling attention to Israel’s war in Gaza.

Four months later, ahead of the new school year, neighboring CMU’s administrators sent an email to campus members highlighting the university’s new policy on encampments — which were banned — along with an update to an existing policy on registering expressive activity events.

It defined expressive activity as any formal advocacy event or effort. This included protests, demonstrations, rallies, speeches, signs and picketing, among other actions.

Some students believe the definition lacks clarity, making it hard to determine what qualifies. CMU Democrats President Avalon Sueiro called the definition “incredibly vague.”

“That could apply to almost any gathering that could ever occur at CMU,” she said.

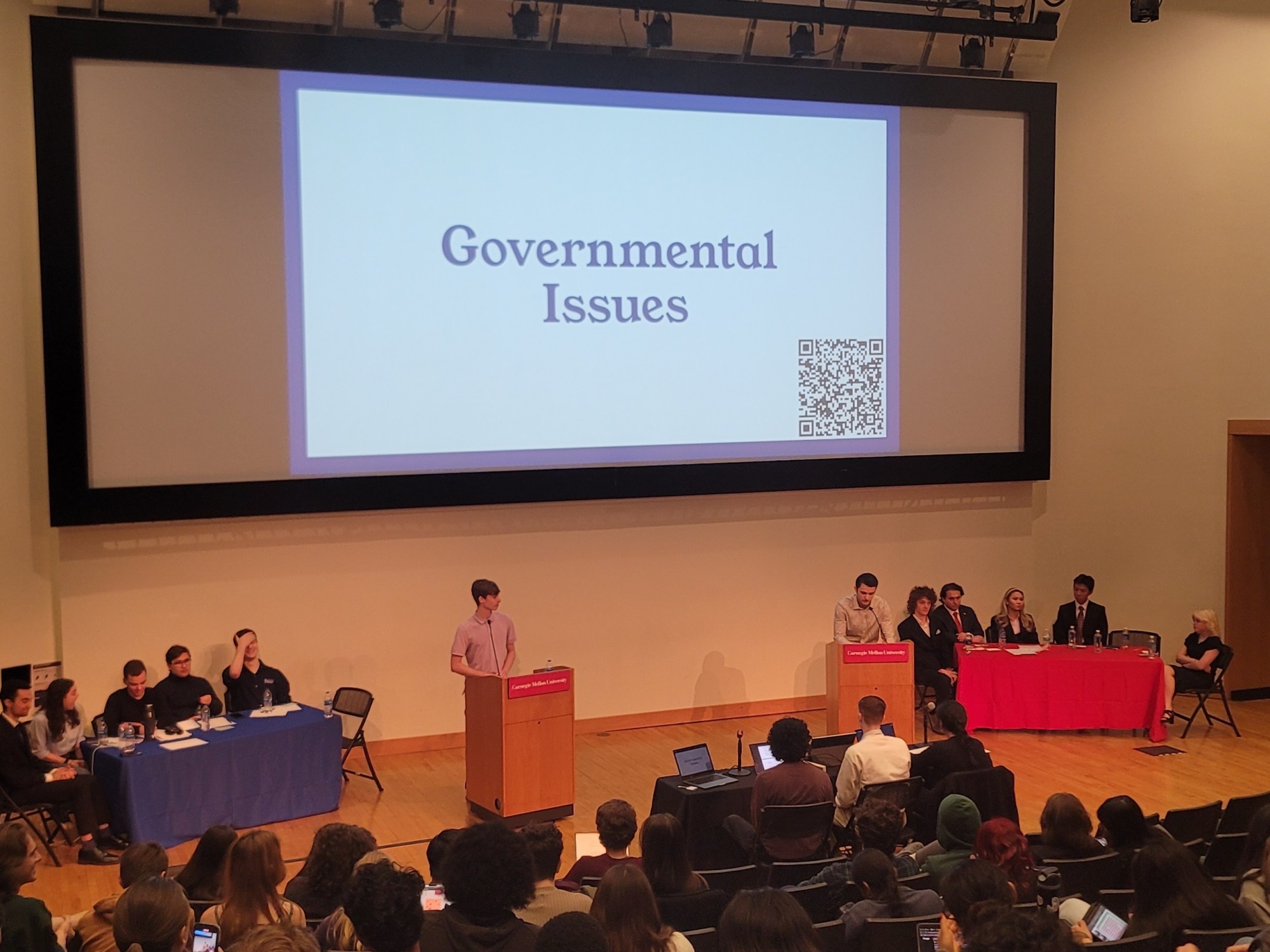

Members of the Carnegie Mellon College Democrats debate members of the College Republicans on April 12. (Courtesy of Avalon Sueiro)

Members of the Carnegie Mellon College Democrats debate members of the College Republicans on April 12. (Courtesy of Avalon Sueiro)

Sueiro said a debate including herself and the College Republicans President Anthony Cacciato in April had to be registered as an expressive activity. The process was “an entire undertaking,” that she said resulted in the clubs spending over $1,000 in security costs.

The two-and-a-half-hour debate drew around 75 attendees, and no security incidents occurred.

Cacciato said he didn’t feel the scheduling process was arduous, but he described it as a bureaucratic one that slows down organizing.

The policy acknowledges that campus members may want to hold impromptu gatherings to respond to current events, but urges that the “safety and normal operations” of the university be considered.

“We live in a very fast media cycle and things happen very fast,” Cacciato said. “Sometimes you need to respond fast.”

Selective enforcement risks

For unscheduled events that hit the 50-person threshold, the university reserves the right to cancel or break them up.

Ross Marchand, a program counsel with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), wrote to Public Source that “while it would be reasonable for the university to shut down a spontaneous event that disrupts campus life … unfettered administrative discretion to shut down events can’t be squared with free speech principles.”

Carnegie Mellon campus members hold papers with numbers 1-29 while protesting the university’s expressive activity policy in August 2024. The policy initially mandated registration for gatherings of more than 25 people. (Courtesy of Jonathan Aldrich)

Carnegie Mellon campus members hold papers with numbers 1-29 while protesting the university’s expressive activity policy in August 2024. The policy initially mandated registration for gatherings of more than 25 people. (Courtesy of Jonathan Aldrich)

History professor Jay Aronson has not been known to protest, but said the current times necessitate it. When the expressive activity policy was first updated, when it was applied to gatherings of 25 people before the limit was doubled, he joined unregistered protests on campus with dozens of people in attendance.

The protests were meant to call the university’s bluff and show that, “except in certain cases,” events weren’t going to be broken up, he said.

At the protests, he said attendees held up numbers to nail this point. Police officers in plain clothes were believed to be monitoring, said Aronson, but “nothing happened whatsoever.”

“It’s the standard law enforcement thing that certain people are to be left alone, to do what they want to do, and others are not,” he said.

In his opinion, the policy was “only about Gaza,” saying that “if there was no discussion about anti-Zionist, anti-Israel protests on campus, none of this would have happened.”

Asked whether pro-Palestinian protests led to the policy updates, a university spokesperson directed Public Source to the frequently asked questions portion of the expressive activity policy’s webpage.

The site states that the updates were informed by “an increase in the volume of expressive activity events” at CMU and on campuses around the country, along with requests by campus members for clarity on event planning.

Sueiro called the policies enacted after the spring 2024 encampments “absolutely unnecessary,” particularly because she said CMU is a STEM-dominant school with demanding programs that don’t leave room for the same kinds of protests that would happen at Pitt.

Encampments or other disruptive demonstrations were “not an issue that faced CMU students,” she said. “I think it was the administration getting very worried about seeing something at Pitt, completely ignoring the fact that that is something that culturally would not happen at CMU.”

Questions of content neutrality

Earlier this year, the local reproductive justice group Auto(nomous) Body Shop came to campus for a health event. The group travels around Pittsburgh, handing out free contraceptives and harm reduction materials from a decked-out van.

The group had approval to be on campus, but staff were approached by CMU police officers and administrators concerning a sign on the van that read: “Free Palestine, End the Genocide.” Police eventually left, while university administrators stayed and asked the group to remove the sign because the event wasn’t classified as an expressive activity.

“It seems to us that, at least in this situation, ‘expressive content’ meant any content about Palestine,” reads a statement from the Auto(nomous) Body Shop that was posted online after their visit. Members of the group declined to speak with Public Source, but confirmed they haven’t been back on campus this semester.

“It’s only when there’s inconvenience or disruption or reaction that you actually get your message across, so Carnegie Mellon has been good about not kind of letting that happen in lots of different ways.”

History professor Jay aronson

CMU’s policy states that it “may place certain restrictions on sound levels, signage and other conditions” for the “physical safety of participants, bystanders and university property,” but the extent to which this is done is based on a “content- and viewpoint-neutral basis.”

David Hudson, a constitutional law professor at Belmont University, said CMU, as a private university, isn’t violating the First Amendment if it uses the policy to target certain content. But, he added, if CMU’s actions aren’t content-neutral, “it directly contradicts a university’s mission to be a bastion of free inquiry, discussion and intellectual exploration.”

University spokesperson Cassia Crogan said the Auto(nomous) Body Shop event wasn’t required to be registered under expressive activity procedures, and that the request to remove “political speech” occurred because it wasn’t related to the event’s purpose. Crogan did not specifically address whether the removal request was made on neutral grounds.

Mounting frustration pushing activists off-campus

Since last fall, few organized actions have taken place on campus.

Academic Workers United, a union effort at the university, held a free speech vigil in response to the policy updates in March. And several petitions have circulated around campus asking for things ranging from the repeal of the updates to CMU President Farnam Jahanian’s resignation, all of which have garnered hundreds of signatures.

Students at Carnegie Mellon University hold out candles at a free speech vigil on March 23. (Courtesy of Jess Vinskus)

Students at Carnegie Mellon University hold out candles at a free speech vigil on March 23. (Courtesy of Jess Vinskus)

CMU did not respond to a question from Public Source about these petitions and their demands.

The latest expressive activity event on campus was a protest attended by fewer than 10 students last month against representatives from the company Boeing, which was tabling for recruits. The representatives were flanked by CMU police officers.

While the university is often considered apolitical with a weak protest culture, the lack of campus action this year has been noticeable and disappointing for some campus members.

Doctoral student Gina Chen said there’s a fear of getting in trouble with university administrators, while Aronson said some students might be hesitant to get involved because they worry about hurting future job prospects.

Frustration over university barriers has pushed some activist students to pursue other avenues — collaborating with those at the University of Pittsburgh or with city groups.

“Any of us who know anything about activism know that activism only really works when some subset of the activists are actually causing trouble, causing disorder, causing inconvenience and causing people to notice them,” Aronson said. “Carnegie Mellon has been good about not kind of letting that happen in lots of different ways.”

The American Association of University Professors said requiring registration for protests “is tantamount to forbidding them,” citing surveillance concerns. “These policies severely undermine the academic freedom and freedom of speech and expression that are fundamental to higher education.”

Future of The Fence in question

The next test of free speech at CMU may be its review of policies covering an often-repainted campus landmark: The Fence.

CMU has cited The Fence as evidence of its commitment to academic freedom and free expression, calling the painted barrier “a self-regulating, student-governed space for open expression for a century.”

Protesters sit guard on July 14 by The Fence at Carnegie Mellon University ahead of the inaugural Pennsylvania Energy and Innovation Summit. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Protesters sit guard on July 14 by The Fence at Carnegie Mellon University ahead of the inaugural Pennsylvania Energy and Innovation Summit. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

However, The Fence was shut down for the first time in its history when President Donald Trump visited for the summit, after it was painted with “No Rapists on Our Campus.”

Students constructed a temporary second fence and positioned it toward Jahanian’s office in protest. The original Fence reopened a week after its closure, but to many campus members, the shutdown signaled a turning point in free expression at the university.

Last month, Jahanian announced the creation of a working group tasked with exploring how The Fence can “continue to serve as a meaningful campus tradition while ensuring clarity, accountability and respect for its roles and the boundaries of its roles.” One of the questions that will be tackled is: “How do, and how should, CMU’s Freedom of Expression Policy and Guidelines apply to the Fence?”

The group consists of three undergraduate students, three graduate students, three alumni, three professors and three staff members. None of the nine campus members Public Source spoke to were hopeful about the outcomes of the group, which will present recommendations to Jahanian by May.

A student activist pours paint to cover a new fence built outside of Carnegie Mellon University’s Wagner Hall in the early hours of July 21. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

A student activist pours paint to cover a new fence built outside of Carnegie Mellon University’s Wagner Hall in the early hours of July 21. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Students paint words on the new fence. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Students paint words on the new fence. (Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Sepinuck said students were “underrepresented” in the group, “especially because students are the people who fund the university and also the ones who interact with this tradition.”

Now, groups including the CMU Democrats and College Republicans are pivoting to make it clear how vital free speech at The Fence is to students.

With an increase in advocacy, Cacciato said, “Hopefully, this can really put some weight on the scale when it comes to changing the trajectory of the administration’s decisions surrounding The Fence, and not just kind of handing it off to a group to kind of solve the problem without solving the problem.”

This kind of alignment from both sides of the aisle is encouraging to students like Jess Vinskus, who is an organizing chair for Academic Workers United.

Vinskus said restriction on expression affects everyone.

“We can’t let this be normal because then it’ll become something that can happen in the workplace. It’ll become something that can happen in local governments, and it’s already something we’re seeing happen in federal government,” they said. “It’s just becoming more and more normalized and it gets really scary.”

Even with bipartisan buy-in on safeguarding speech on The Fence, there’s continued friction about inappropriate speech and how it should be dealt with.

On Oct. 22, Cacciato released a statement condemning a CMU Democrats leader for allegedly writing controversial messages during a campus event, ranging from “kill cops” to “murder transphobes.”

“While our club unequivocally supports free expression … free speech does not protect individuals from repercussions for the views they express, especially when the speech is calling for acts of violence,” the statement read.

CMU Democrats did not respond to questions about the allegations by publication time.

Cacciato is now asking for the CMU Democrats to remove the leader from their position, and for university administrators to “consider appropriate steps” regarding the student.

Maddy Franklin reports on higher ed for Pittsburgh’s Public Source, in partnership with Open Campus, and can be reached at madison@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Bella Markovitz.

RELATED STORIES

Your gift will keep stories like this coming.

Have you learned something new today? Consider supporting our work with a donation.

We take pride in serving our community by delivering accurate, timely, and impactful journalism without paywalls, but with rising costs for the resources needed to produce our top-quality journalism, every reader contribution matters. It takes a lot of resources to produce this work, from compensating our staff, to the technology that brings it to you, to fact-checking every line, and much more.

Your donation to our nonprofit newsroom helps ensure that everyone in Allegheny County can stay informed about the decisions and events that impact their lives. Thank you for your support!

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.