Stories of ghost encounters have long relied on the same descriptors. Chief among them are the diaphanous Lady in White and the featureless, shadowy Hat Man, which have, over time, become so omnipresent in paranormal lore as to be cliché at this point.

Pittsburgh boasts more than its fair share of ghosts defined by period outfits or other characteristics. The employees of one Lawrenceville restaurant claim repeated sightings of a “pale young woman,” while Chatham University — a school that, based on its own accounts, is abundantly haunted — has a Blue Lady that roams Woodland Hall.

However, Pittsburghers have also named the ghosts haunting various spaces, all in an apparent attempt to add significance, character, or, in some cases, legitimacy to supposed sightings. These ghosts are sometimes used to brand a business, as is the case with Harold’s Haunt, a queer-friendly Millvale bar named after a resident “malevolent presence,” or acknowledge the city’s history, which stretches back to the American Revolution.

At the University of Pittsburgh, history is depicted in the Cathedral of Learning’s Early American Room, described as emphasizing “life in the 17th century (New England) for early English settlers.” But the room has become known for more than its worn wood furniture and heavy iron fixtures — ghost hunters and paranormal investigators know it as housing the spirit of Martha Jane Poe McDaniel, whose handmade quilt, donated by her granddaughter E. Maxine Bruhns, former director of Pitt’s Nationality Rooms Program, spreads across the two-floor, life-sized diorama’s four-poster bed.

But, according to Michael Walter, the manager of education programs for the Nationality Rooms and Intercultural Exchange Program, they don’t talk about Martha anymore.

“Because it was entirely fabricated by [Bruhns],” he tells Pittsburgh City Paper. “And it was something that she perpetuated because it was good publicity for her.”

Walter says they decided to put a stop to the legend a few years ago because it obscured the “unique history” of the Early American Room and the Cathedral’s 30 other Nationality Rooms, each of which highlights a different country or culture.

“We would have groups come in and sign up for a Nationality Rooms tour and say, ‘We want to go to the ghost room,’” he says. “And they didn’t even know there were other rooms that had interesting stories to tell.”

While some were curious about the ghost, he says the stories also scared away school groups with young children.

Bedroom of the Early American Nationality Room at the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning Credit: Aimee Obidzinski/Courtesy of University of Pittsburgh Communications and Marketing

Bedroom of the Early American Nationality Room at the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning Credit: Aimee Obidzinski/Courtesy of University of Pittsburgh Communications and Marketing

The development might disappoint believers, especially those claiming they saw Martha fluff pillows or move objects in the room (as reported by Pitt’s own publications). But Walter believes it stands as an example of “fake lore,” which may seem folkloric but has no basis in a “shared community story.”

Walter says Bruhns, who died in 2020, “wanted to believe” that her grandmother was in the Early American Room, adding that she even spent an evening there to collect evidence. “She freaked herself [out] just by her imagination and left, and then talked about it for decades,” he says, recalling how Bruhns then blamed various incidents on the ghost, including a water bottle falling out of her backpack and, more perplexingly, her home toilet exploding.

Despite being initially freaked out, Bruhns would go on to host Halloween night events in the room, encouraging people to join her and tell spooky stories.

With Martha’s ghost finally put to rest, so to speak, Walter says the Nationality Rooms program, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, will focus more on its stated mission, benefitting the school and broader community “intellectually, empathetically, and socially” through the “preservation and sharing of cultural knowledge through educational programming.”

“We’re accentuating the abundance of valuable creativity of cultures that make up this region,” he says.

Anyone interested in seeing the Nationality Rooms program in action can attend various events, including a free upcoming Holiday Open House on Sun., Dec. 7, during which guests can experience a wide range of festive cultural traditions, cuisine, music, and more.

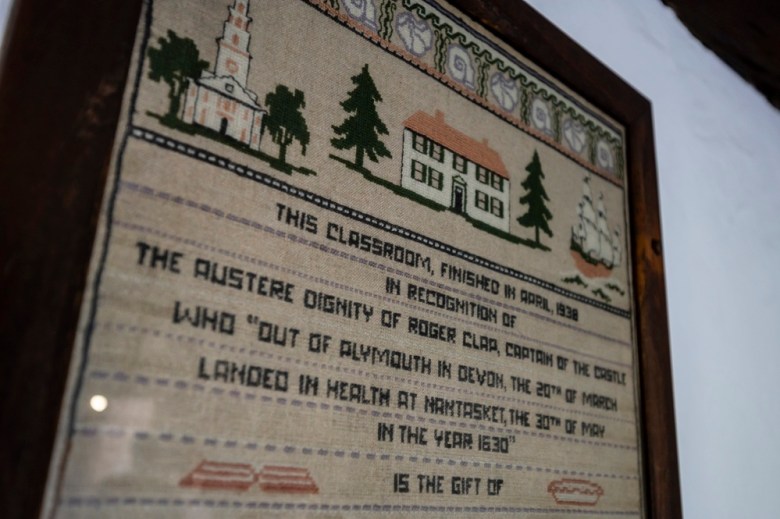

Sampler in the Early American Nationality Room in the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning Credit: Aimee Obidzinski/Courtesy of University of Pittsburgh Communications and Marketing

Sampler in the Early American Nationality Room in the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning Credit: Aimee Obidzinski/Courtesy of University of Pittsburgh Communications and Marketing

Still, Martha’s fabricated legend appears relatively harmless compared to the gruesome origins of other Pitt ghosts. Walter recounts how, while attending an on-campus party, caterers told him about the mistress of a former chancellor who died by suicide in Bruce Hall, where her restless spirit now roams.

Much like the Bruce Hall spectre, other local ghosts carry tragic stories. One such case, Slag Pile Annie, speaks to the city’s industrial past and the dangers it often posed to workers. Thomas White, an author and adjunct professor who also serves as an archivist and curator at Duquesne University, wrote about Annie in his book Supernatural Lore of Pennsylvania, detailing her horrific demise while working at the Jones & Laughlin steel mill in Hazelwood during World War II.

“She drove a hopper car and picked up slag after hot steel was poured into molds,” White tells City Paper. “The legend says that one day, while she was shoveling slag near a recently poured vat of steel, a bubble of hot metal (possibly caused by impurities) exploded from the vat. The intensely hot liquid metal landed on Annie, who was almost instantly melted and killed.”

He says that, over the years, workers reported seeing Annie’s ghost in the area in which she was killed, and that she “even interacted with at least one young man who was doing the same job that she once had.” White also points to a similar story about a steelworker named Jim Grabowski who, in 1922, fell into a vat of steel at the J&L Steel South Side Works.

White says Annie and Grabowski represent the “very high numbers of casualties in steel mills in the region,” during which it was “not uncommon for people to be killed by molten steel in accidents.” In some instances, the reality is more grisly than any ghost story.

“In the back of J&L’s slag dump was the ‘graveyard,’ where pieces of steel with human remains in them were put,” White says. “There were over 100 of them by the outbreak of WWII.” He says Grabowski met this fate, and, as a result, his “‘melting’ ghost” has been seen by “dozens of witnesses over the years.”

Still, White believes Slag Pile Annie was “definitely based on a real person or persons,” recalling a period when women “began working in large numbers in the mills during the war.”

“The story (whether something supernatural was actually going on or not) serves as a form of history or community memory — a reminder of the women who worked in the mills during the war and of those who paid the ultimate price doing so,” says White. “The story also had a practical purpose. When it was repeated in later years, it served as a reminder of the dangers of the work and why one had to be extra vigilant.”

He sees Pittsburgh as “at the crossroads of the majority of folk traditions” that arrived in the U.S., especially from Europe. He believes the impulse to keep these legends alive, regardless of their truthfulness, demonstrates Pittsburghers’ need to “retain their identity.”

“Western Pennsylvania has a very high number of ghost stories and legends as compared to many other parts of the country,” he says. “The population has been relatively stable over time, and it has allowed these stories to flourish and be passed on through multiple generations.”

Walter goes a step further, explaining how dubbing ghosts with distinct names and identities speaks to something deeply human.

“To say that you have something in your neighborhood gives people a sense of shared ownership, even if it’s something that is spooky, metaphysical,” he says. “Then there’s the aspect that’s just human psychology. The belief in the existence of ghosts is sort of a left-handed way of approaching the idea of afterlife. So, the unknowable that is showing some small evidence of being knowable, it gives a sense of a little bit of control, and also a little bit of dramatic lack of control.”

This article appears in Oct. 29-Nov. 4, 2025.

RELATED