There’s a certain threshold of pain one must be willing to endure when living in Philadelphia — including whichever flavors of crime and neglect characterize your particular neighborhood, which may or may not bother you. Some people just shrug and say: “It’s a Philly thing.”

The question a reporter must pose is: At what point does an issue become more than a nuisance and something worth investigating? For this reporter, it was when my neighbor Jenny recounted a recent argument with a package thief who wears a fake Amazon vest, walks through Northern Liberties like he does most days, dragging a stolen trash can to collect packages like a reverse Santa Claus. This vignette comes just days after what seems to be the same man stole a package of mine, caught on a Ring camera, with two more packages of mine stolen in as many weeks before that.

We were hardly alone: Package theft in our metropolis occurs at a rate topped nationwide only by New York City. Philadelphia’s losses amount to an estimated $450 million in the value of packages stolen in 2024, according to a May 2025 report by the USPS Office of the Inspector General (OIG), which also includes private carrier data.

It turns out that all those stolen packages you might think are too small to report to police in fact add up — an estimated $5 billion to $16 billion last year, according to the OIG report, with the total at $15.7 billion, according to a more recent, FBI crime data-based report from marketing firm Omnisend.

New York leads with about $950 million in losses for 2024, but it’s worth pointing out that New York also has about 7 million more people than Philly. That puts losses at about $113 for each New York resident, and about $290 for each Philadelphia resident. The cities that follow in terms of scale of package theft are Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Houston.

Why is package theft so frequent? Is anyone doing anything to stop it? Do the police even care? And, importantly: Is there anything we can do about it?

“These are not victimless crimes.” — Pennsylvania State Senator Frank Farry

But first, to finish Jenny’s story, she told the thief she caught him on camera stealing her package, because up until that point, he had refused to give it back, despite her staring right at it sitting in the trash can with the rest of that day’s haul. Finally, he handed it over. It was a head and neck massager. “This man was interfering with [alleviating] my chronic pain,” she says with a laugh.

Urban areas experience higher rates of package theft due to easy access and high population density. But Philadelphia stands out as an embarrassing anomaly due to the volume of theft proportionate to its population. Anecdotally, no matter which neighborhood I’ve lived in, package thieves seem to be getting faster and more prolific. Managing deliveries, monitoring notifications, rushing home or coordinating with a neighbor: It’s all part of the time-suck required to avoid theft. Imagine how much your time is worth when dealing with this.

Prolific porch piracy is a felony

U.S. Congress has failed twice — in 2022 and 2024 — to pass the “Porch Pirates Act of 2022,” which would trigger federal penalties for stolen mail or packages delivered by private and commercial interstate carriers. Currently, package theft is a federal felony only if the package is delivered by the USPS. The consequences of package theft by a carrier other than the USPS, thusly, falls to the states.

In Pennsylvania, State Senator Frank Farry, who represents part of Bucks County, including Bensalem, sponsored SB 527, which was enacted in December 2023 and established mail theft as a discrete crime, separate from property or other kinds of theft. The bill is now Act 41. It increases penalties up to a felony for repeat offenders and the theft of items valued at more than $2,000.

“These are not victimless crimes,” says State Senator Farry, citing elderly people whose medication gets stolen or parents who can’t afford to replace holiday gifts.

Photo by Kristen Demilio

Photo by Kristen Demilio

The impetus for the PA law, says Farry, was then-District Attorney Matt Weintraub, now a Bucks County Court of Common Pleas judge. Weintraub was unable to effectively prosecute package thieves, because as he told Farry: “‘It’s not even a slap on the wrist they’re getting because there’s not much we can do with them.’”

Farry’s legislation tees up the ability for prosecutors to crack down on serial offenders, not only by making the sixth offense a felony, but also by aggregating the value of the items stolen. If a porch pirate steals $2,000 worth of total goods in three separate thefts, the suspect can be charged with $2,000 in theft, rather than three separate summary offenses citing smaller amounts, which is how Pennsylvania law previously classified this type of theft.

So the problem is not with the law. Act 41 tightens outdated measures for mail theft and is part of Farry’s focus on “evolving crimes,” whereby social media and online shopping have changed the landscape for retail and mail theft. The problem is with enforcement — and prevention.

“We arrest them, he cuts them loose.”

Maybe unsurprisingly, a whole lot of people who could be working on the problem seem to be passing the buck instead.

I remembered a conversation I had during the pandemic with a Philadelphia police sergeant (as a Philly resident, not as a journalist). There was a notorious heroin dealer on my block and the sergeant went off on a tangent about District Attorney Larry Krasner, saying how many complaints the police get about quality-of-life issues, particularly rampant package theft.

“Krasner lets them all walk,” he said at the time. “We arrest them, he cuts them loose.”

Before diving further into the DA’s record on package theft, let’s first look at what happens before charges land in front of a prosecutor. The USPS report notes that fragmented data complicates efforts to track the scope of package theft. “The absence of an industry-wide reporting system makes it difficult to aggregate and analyze theft data comprehensively,” the report states. “Victims of theft may file complaints with delivery companies, law enforcement or retail organizations, but these entities often do not share or aggregate data.” Companies absorb the losses and replace the item in order to stay competitive, almost always without the need for a police report, according to the OIG.

Package theft in our metropolis occurs at a rate topped nationwide only by New York City.

One spokesperson for the DA’s office asked for more time to get The Citizen data about the number of mail theft prosecutions led by the Krasner’s office. After multiple follow-ups, that information never arrived.

Krasner’s opponent in the November 4 election, former Judge Pat Dugan, was, however, happy to comment on the DA’s record: “Krasner won’t prosecute quality of life crimes,” he said in an email before the election. “We should prosecute package theft — and most of these incidents are caught on Ring doorbells. Theft is a crime! Not prosecuting these crimes erodes our Philadelphia neighborhoods.”

While the DA’s office provided no data on package theft prosecutions, it must also be noted that the total is nearly impossible to quantify because no one — not the City, not the state, not the PPD — is specifically tracking reports, arrests or prosecutions of package theft.

Farry says his legislative director has been trying to obtain mail theft data “for months,” and his office confirmed that as of publication, none has been produced. Nor does the Administrative Offices for PA Courts in Harrisburg keep track of mail theft prosecutions. “We don’t have that data,” a spokesperson said over the phone. “We can’t pull data of prosecutions by statute [in this case, mail theft]. We’d have to write special computer code for a fee in order to retrieve that information,” but added that she can’t say what that fee I’d have to pay without a written request.

Looking more broadly at property theft in Philadelphia, which includes burglaries and all types of theft, the PPD tallied 11,916 incidents in 2024. Of that figure, 916 landed at the DA’s office, with 228 convictions and 19 acquittals.

Here’s how the pipeline works: Officers make arrests, then pass the information to detectives, who fill out the paperwork itemizing all applicable charges. Detectives then submit the charges to the court system, says 9th District Captain of the Philadelphia Police Department Anthony Ganard. “We push through the charges on our end and then after that, we let the courts deal with it,” he says.

Ganard has spent most of his career in West Philly, and came over to the 9th [which covers parts of Center City, Fairmount, Spring Garden and Northern Liberties] in July 2024. Soon after his arrival, Ganard created a property-crime team that has since added mail theft to its portfolio. “Over the past 30 to 60 days, we started including package theft in that team because we’re seeing a lot of crossover between retail thefts, theft from autos, residential burglaries and package thefts,” says Ganard. Since the effort began, Ganard says his officers have made three arrests for package theft.

There’s a “but”: The police can’t take action against package theft if members of the public don’t report it. “I looked up the last 90 days in Northern Liberties,” says Ganard. “We’ve only had two reported incidents over there.”

There are two ways to report: Go down to the precinct in person and file a report, or else call 911. It’s a tough sell to ask the public to call 911 over a lower-grade theft, and then wait potentially hours for an officer to come out, or else go down to the precinct. No one I talked to for this story reports package theft to the police, even when the thief is caught on camera. One reason I heard from residents is that they have in fact called 911 and no one ever showed up.

While the DA’s office provided no data on package theft prosecutions, it must also be noted that the total is nearly impossible to quantify because no one — not the City, not the state, not the PPD — is specifically tracking reports, arrests or prosecutions of package theft.

Ganard says the precinct is aware the theft-reporting process is cumbersome, and says his team is working on creating an email address that victims of package theft can use to file police reports rather than call 911. He says that the police use a priority scale, with the most urgent matters taking resources, and that the lower the report is on the scale, the less urgency it has. It’s why he is telling the public that while incident reports will raise crime statistics, people must report the theft in order for the police to deploy more resources to combat it. Without reports, in terms of how police view it, there’s no crime. Any solution to package theft has to start with data showing it’s a problem, and that means that no matter how small, citizens must report it. From a police perspective: Without incident reports, no crime exists.

“I understand it’s a lot easier just to call Amazon and say, ‘Hey, my package was never delivered,’ and then they end up delivering a new package,” Ganard says. “But I do a lot of data-driven deployment, and without having the [police] reports being taken, it’s hard for us to do anything about this on our end.”

Over the course of reporting this article, my partner actually caught someone stealing a neighbor’s package from the mailbox depot in our development. After exchanging video with Jenny, we concluded that this person appears to be the man with the trash can.

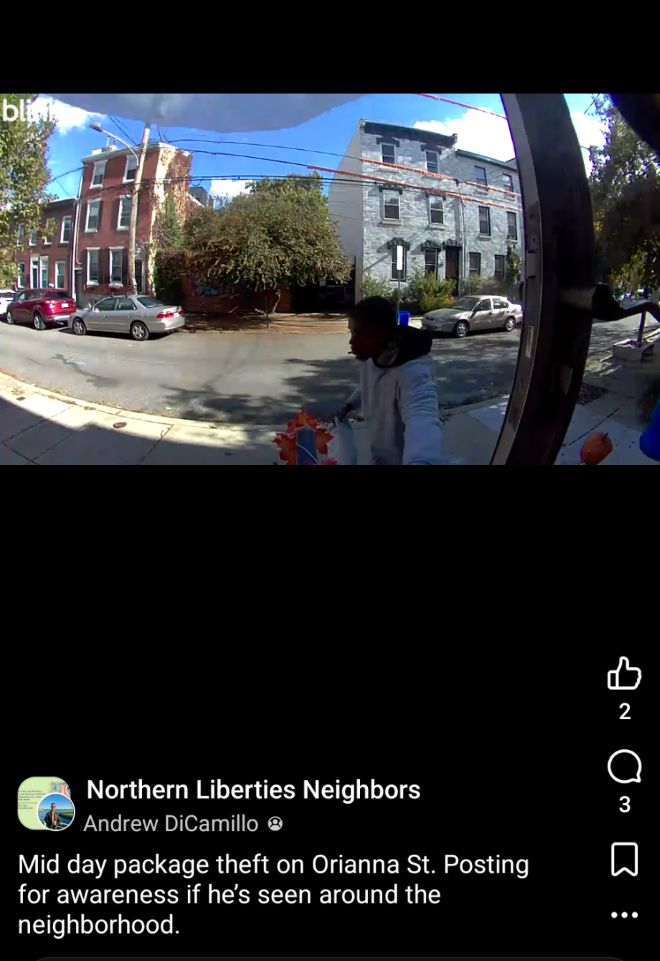

A social media post sharing ring footage of a theft in progress

A social media post sharing ring footage of a theft in progress

The thief pretended he didn’t realize the large Crate and Barrel package belonged to someone else, and as with Jenny, again didn’t want to give it up. When he finally did, we returned it to the owner, who had no idea it had even been delivered. His girlfriend was away and he didn’t know about the order, he says. When I suggested he file a police report, especially since I caught the theft on camera and would provide video, he said he wasn’t about to call 911 over it. “It happens all the time,” he says.

Speaking of which, at Liberties Parcel in Northern Liberties, where I pay for a package-collection service, ostensibly to avoid package theft, thieves still grab deliveries outside the storefront, says co-owner Dan Streckewald. The store collects packages for an estimated 500 customers, he says. Despite very large and clear signage on the front door indicating packages should never be left outside, some carriers do it anyway, which is why packages are regularly stolen, including mine, by the fake Amazon driver.

The store’s staff does not report these incidents to police “because they’re not our property, and the theft isn’t happening on our property,” says Streckewald. But he makes video available to customers who wish to file a police report.

“We’re seeing a lot of stuff being posted online about [package theft], but we’re not getting actual reports,” Ganard says.

“One thing I’d love for people to know is that there is a lot of crossover with the different types of crime, so our focus isn’t like: Hey, we want to go out and arrest everybody for stealing a $10 shirt or something,” says the police captain. But the problem is that the same [package theft] offender is not unlikely to be committing other crimes because they see an opportunity.”

At Liberties Parcel, Streckewald summed up the way dozens of residents interviewed for this story generally feel: “From our perspective, there are repeat guys out in this neighborhood who are well known, well documented, and get seen day in, day out by you, by ourselves, by other people. They’re caught on our cameras. They’re caught on everybody’s cameras walking around with the same trash cans, same trash bags, same book bags. And the number of people doing it is actually growing every day.”

![]() MORE SOLUTIONS TO CRIME IN PHILLY

MORE SOLUTIONS TO CRIME IN PHILLY

Photo by Christina Griffith. Not an actual theft in progress.