At first, JoAnne Woods just wanted to make it easier for her neighbors in Upper Roxborough to enjoy the nature that surrounds them in Wissahickon Valley Park. A staff member at the Free Library’s Andorra Branch for 22 years, Woods had noticed that “Families were finding the library, but not the amazing park system right outside.”

Her idea, in 2017, was simple: Lend “Birder Backpacks,” with binoculars, field guides, and trail maps, the way the library lends books. “Binoculars seemed like a good way of getting people outside,” she says.

Eight years in, Philadelphians are checking out backpacks from 20 branches, exploring their neighborhoods, and discovering the city’s birdlife, finding ways to connect with nature and with one another — real contact with real people in real places.

In the past two years alone, Philadelphians have checked out the backpacks more than 1,600 times. One branch, in Port Richmond, had a run on the backpacks when an owl was using the rowhome-rich neighborhood as a hunting ground. Woods says her colleague Amy Thatcher told her, “The community went crazy for birds when a snowy owl landed on the library and hung out in the neighborhood.”

“Everybody checks them out,” says Woods. “Kids as young as six can see something meaningful through binoculars. Seniors love them. We’ve even done non-walking programs, just watching feeders.”

JoAnne Woods with a Birding Backpack Public Space is the Place

JoAnne Woods with a Birding Backpack Public Space is the Place

The idea of lending birding backpacks began with one spirited question: What else could a library let you borrow? In Philadelphia, where cake pans, musical instruments, and even job-interview neckties were already in circulation, the notion felt both playful and practical.

Knight Foundation became the first funder of the program in 2016, sharing the incubator costs with The Free Library of Philadelphia Foundation to outfit 39 backpacks with binoculars, field guides, and trail maps for three branches.

Knight’s early support also connected it to the then-recently formed Reimagining the Civic Commons, situating the project in a broader effort to strengthen public spaces and civic life. Additional funding has come from the Whitemarsh Foundation, with ongoing support from the City’s Department of Parks and Recreation and the Fairmount Park Conservancy. Most recently, the Pennsylvania Game Commission joined the effort — donating more than 100 pairs of binoculars; its education specialists are helping libraries bring birding to neighborhoods citywide.

Partners include the Wissahickon Environmental Center, Schuylkill Center, and the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club, as well as an eclectic mix of birding clubs throughout the region.

The library has always been part of the American experiment — built on shared resources, shared space, shared fate. Strong libraries build stronger communities. A new ribbon-cutting at Richmond Library and another at Nixon Library in Cobbs Creek — from Parks & Rec’s Rebuild PHL team — hints at steady step-wise shifts.

“A librarian knows how to invite many hands into the work of cultivation for the good of all,and can introduce us to the tools we need to govern ourselves — knowledge of our past, skill for the present, curiosity about the future.” — Eric Liu

Despite daunting sea changes, funding cuts and book bans powered by the culture wars, libraries are steadily renewing their role as anchors of civic life. Librarians are meeting the flood of online culture not by fighting it, but by offering what the internet cannot: a place where the world and our lives meet.

In Meet Me at the Library, urban libraries advocate Shamichael Hallman positions the library as a living commons — not a relic of the past, but a cornerstone of a shared future. For Hallman, the library is a bridge-space where elders, artists, youth and small business owners appear as co-authors of public space. Librarians serve as cultural facilitators, opening space for those encounters to take shape.

He frames everyday collaboration as the core mode of a healthy commons: iterative, reciprocal, and rooted in shared stewardship. His research echoes initiatives like the Birder Backpack, underscoring their potential as models. He also points to similar efforts like the “Library of Things,” where everyday tools — cookware, sports gear, board games — become shared resources.

Hallman is part of a growing network of pragmatic problem solvers, built on a legacy of work, that connects design, community, data, and partnerships to strengthen communities through civic infrastructure. In the foreword to Hallman’s book, Eric Liu casts the story in civic terms. “A librarian knows how to invite many hands into the work of cultivation for the good of all,” he writes, “and can introduce us to the tools we need to govern ourselves — knowledge of our past, skill for the present, curiosity about the future.”

Hallman’s role as Senior Library Manager of the Cossitt Library in Memphis from 2017 to 2022 is also tied to his work with Reimagining the Civic Commons (RCC), a national network that champions civic spaces as places for connection and public life. The overlaps are clear: RCC and Knight Foundation were the Birder Backpack program’s first partners. In fact, RCC itself began in Philadelphia as a 2015 pilot, led by William Penn Foundation and Knight. Today, the network spans 10 cities. Hallman and Woods show that even with national initiatives behind them, real change often starts small: a park bench, a conversation, a shared idea, a room — bird by bird.

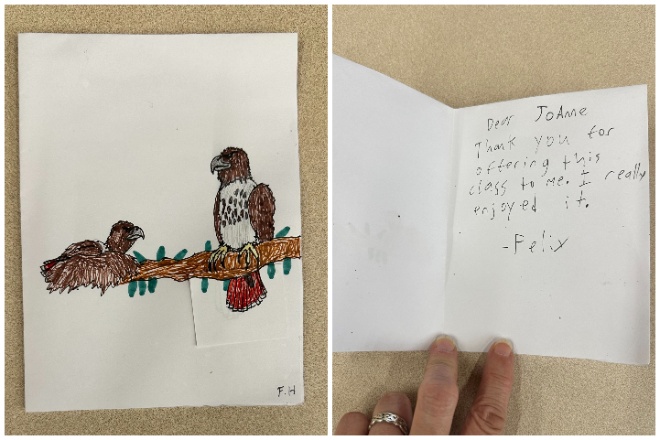

Young Felix expressing his appreciation Roots and wings in practice

Young Felix expressing his appreciation Roots and wings in practice

“I’d love to see every branch have a backpack,” Woods says. That would mean growing from 20 branches today to all 54 across the city. Someday she also hopes to shift her work from branch manager to a more formalized system-wide role — a dedicated Free Library position focused entirely on nature programs and services.

Woods is also thinking about who hasn’t yet had access. As she works to expand the program — including to the Library of Accessible Media for Pennsylvanians — she’s collaborating with local artist and lifelong birder Katrina Rokowski to create tactile bird illustrations. Known for the vividness of her drawings, Rokowski’s work will be rendered as raised images that allow people who are blind or have low vision to trace each bird’s shape and details, using Swell Form printing technology.

When someone checks out a backpack, they are handed a card with a QR code and prompt. “They have the Bird Philly card — it sends them to the website to find a walk, so now they’ve got something to do,” Woods says. “They have maps, places to go. It empowers people to explore outside and also meet up with other people. There’s that social element to it as well.”

Woods says people are still talking about the day a red-tailed hawk landed above a small group of students and Woods at a park trailhead. Eyes wide, stock still — the life force pressing in.

“People see something cool,” Woods says, “and then they want to see everything. That’s not just kids. It’s everybody.”

For one seventh grader named Felix, it wasn’t the hawk’s blazing eyes or its talons that left the deepest mark. It was the sheer span of its wide-spread wings before it fully settled on a nearby branch. A red-tailed hawk at arm’s length wasn’t in the lesson plan.

Weeks later, Woods received an email from Felix’s mother: He was reading everything he could about raptors, filling notebooks and scraps of paper with pen, pencil, and marker sketches. Then a thank you card arrived for Woods.

At our meeting with Woods on a recent Thursday at the Andorra Library, I asked to see the card. There was a full-color drawing of the hawk on the right side of the branch, and on its outer edge, a hatchling in a nest. The drawing is impressive, but sharp eyes may also notice the dynamic in it: It’s the hawk and li’l Felix as the fledgling — both a double portrait and a creation story together.

“People see something cool,” Woods says, “and then they want to see everything. That’s not just kids. It’s everybody.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misattributed an attribution in a pull quote. The correct writer was Eric Liu.

![]() MORE ON GOING OUTSIDE TO PLAY

MORE ON GOING OUTSIDE TO PLAY

JoAnne Woods at the Andorra Library. Photo by Thomas Devaney