Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh tries to adjust to changes in student visa policies. (Graphics by PublicSource)

Carnegie Mellon University annually attracts thousands of students from more than 150 nations with its highly ranked degree programs and abundant research opportunities. But this year, amid geopolitical tensions and tightening federal immigration policy, those numbers edged down.

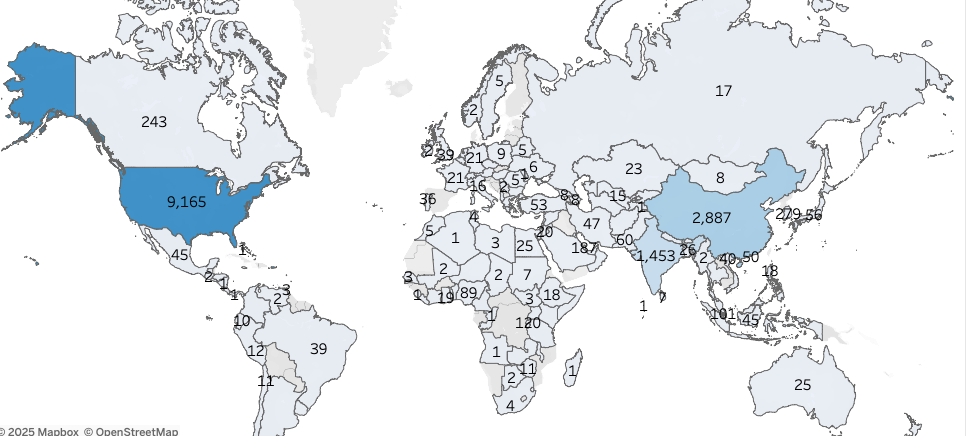

Compared to last fall, there are currently 223 fewer students enrolled from China and 272 fewer students from India, for instance. That’s a dip of 7% and 15% respectively. A spokesperson for CMU acknowledged that international enrollment is “down in undergraduate and graduate programs,” but said that this decline is “smaller than that experienced by many other institutions.”

The United States, China and India remain the most significant countries of origin for Carnegie Mellon University students according to this map from CMU’s data dashboard. (Screenshot)

The United States, China and India remain the most significant countries of origin for Carnegie Mellon University students according to this map from CMU’s data dashboard. (Screenshot)

In 2020, U.S. universities experienced a steep drop in international enrollment as COVID-19 swept the globe, but numbers quickly rebounded. Now, international enrollment is facing new pressure from a changing U.S. immigration system.

Some U.S. policymakers are concerned about the perceived threat of international students, particularly Chinese students in STEM fields. And increasingly feverish language on the strategic rivalry between the U.S. and China — some of which has been heard on CMU’s campus this year — could also dent future international enrollment.

“I have international grad students who are scared and freaked out right now, and don’t feel welcome in this country,” said Carrie McDonough, a professor of chemistry at CMU.

Chemistry professor Carrie McDonough investigates organic pollutants at Carnegie Mellon University. (Photo courtesy of Carrie McDonough)

Chemistry professor Carrie McDonough investigates organic pollutants at Carnegie Mellon University. (Photo courtesy of Carrie McDonough)

In the 2023-2024 academic year, U.S. universities enrolled more than 1.1 million foreign students. While nationwide enrollment figures for the 2025-26 academic year are not yet available, other metrics are.

For instance, data from the U.S. National Travel and Tourism Office show that 19% fewer international students entered the U.S. in August 2025 than during the same month last year. In Pennsylvania, the number of visas issued to Chinese and Indian students has dropped by 6% and 4% respectively, according to the Department of Homeland Security’s Student and Exchange Visitor (SEVIS) database.

Restrictions on international students could also hinder U.S. innovation, as CMU President Farnam Jahanian noted at a July AI summit on the campus. He said then that “we … need to have an immigration policy that allows us to recruit the best and the brightest to come to this country,” and pointed to data indicating that 90% of CMU’s international .”

The China scare and visa insecurity

Contrary to Jahanian’s recommendations, many U.S. policymakers are seeking to limit international enrollment due to security and economic concerns.

On March 19, the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party sent a letter to CMU and five other universities urging them to curtail their enrollment of Chinese students due to a fear of espionage and the subsequent loss of U.S. technological supremacy. “As China aggressively pursues dominance in strategic industries, the unchecked enrollment of Chinese nationals in American institutions risks facilitating the technological transfers that strengthen Beijing’s military and economic competitiveness at our nation’s expense,” the letter said.

In late March, the State Department followed up by revoking hundreds of student visas across the country, sometimes without warning, claiming the recipients were suspected of taking part in “activities that are counter … to our national interest.” Then in May, visa interviews were paused for three weeks to expand the vetting process, limiting the number of foreign students who could be admitted this semester.

Carnegie Mellon University President Farnam Jahanian (Courtesy of CMU)

Carnegie Mellon University President Farnam Jahanian (Courtesy of CMU)

According to McDonough, once the U.S. government showed its willingness to swiftly revoke visas, many international students stopped voicing their political beliefs around campus. “A lot of people feel really scared about saying anything that might be construed as un-American.”

For many, a student visa is the first step toward permanent residence. Research by the National Science Foundation shows that 73% of foreign PhD recipients who study science or engineering in the U.S. remain after graduation, while, according to a separate study by the Economic Innovation Group, only 17% of bachelor’s recipients stay.

‘There’s really no incentive to coming here’

CMU has not been spared from visa revocations.

On April 7, Jahanian notified students and faculty that “two current CMU students and five recent graduates had lost their visa status.” The students were given no reason for the revocations, although one who came forward with their story suggested it could be related to an expunged DUI case from 2023.

Six of the seven individuals soon had their visa status restored, but the move sent a chill through the international community. In the words of a Chinese-born graduate student who spoke with Public Source but asked to remain anonymous, the message was: “America don’t welcome you, you can come here to study, but be prepared to leave sooner or later.”

For those seeking longer-term U.S. residence through a work visa, the outlook is no more promising. In September, the administration introduced a $100,000 fee per H-1B visa, likely limiting the number of foreign workers that U.S. companies are able to hire. Public Source spoke with two Chinese graduate students at CMU who expressed that their plans to work in the U.S. after graduation may be thwarted by this new fee.

“I think we are at the peace before the storm,” one said. “What is now in contention is the policy position, the idea that America is a country that welcomes foreign talent.”

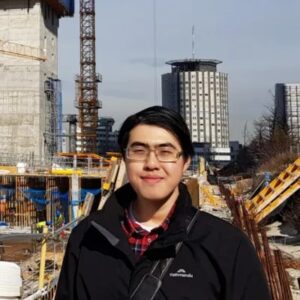

Korawich Kavee, a Thailand native and PhD student in CMU’s College of Engineering said even highly ranked American schools could struggle to attract foreign students like him if the U.S. keeps to its current path.

Korawich Kavee, a Thailand native and PhD student in Carnegie Mellon University’s College of Engineering. (Photo courtesy of Korawich Kavee)

Korawich Kavee, a Thailand native and PhD student in Carnegie Mellon University’s College of Engineering. (Photo courtesy of Korawich Kavee)

\\

“Basic safety concerns, how is it going to work in terms of the visa, or in general the cost of living” are likely to make the U.S. less appealing for prospective students in Asia. “People can go to Canada, people can go to the UK, people can go to Australia,” he pointed out.

This changing visa policy doesn’t pose an immediate problem for Kavee, who will return to Thailand after graduation, but it does have “a strong impact on those who are thinking of coming to the U.S.,” he said.

A decline in international students could hit CMU hard. According to a dashboard maintained by the university, roughly 40% of CMU students and 14% of faculty have been foreign born since it began collecting data in 2021. The school’s primacy in fields like computer science and AI rely heavily on its ability to attract, as Jahanian put it, the “best and brightest.”

‘Our war with the communist Chinese’

On July 15, CMU took center stage as host to U.S. Sen. Dave McCormick’s Energy and Innovation Summit. The event brought together leaders of industry, academia and government to discuss the opportunities and risks of artificial intelligence.

McCormick, a Pennsylvania Republican, took the opportunity to announce that $90 billion of investments will come to the state to develop AI data centers powered by natural gas. He promised that “tens of thousands of jobs” will come to Pennsylvania if the region embraces the “AI revolution.”

Many speakers, though, raised concerns about a looming AI race with China, framing it as a matter of national security.

Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum said that “losing the AI arms race” was one of the “existential threats” facing the United States. Secretary of Energy Chris Wright compared the current situation to World War II, claiming that “AI is our second Manhattan Project.” Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei spoke about the ability of AI “to find the needle in a haystack, the next September 11 … The better our AI can be, the better we will be able to contend with what our adversaries are able to do.”

Carnegie Mellon University President Farnam Jahanian, right, speaks at the AI Horizons Summit alongside Gov. Josh Shapiro, center, and other panelists. (Photo by Eric Jankiewicz/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Carnegie Mellon University President Farnam Jahanian, right, speaks at the AI Horizons Summit alongside Gov. Josh Shapiro, center, and other panelists. (Photo by Eric Jankiewicz/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Throughout the discussion of threats and adversaries, China was repeatedly singled out as the primary concern.

“If the United States does not lead this revolution on our own terms we will hand control of our infrastructure, our data, our leadership and our way of life to the Chinese Communist Party,” said McCormick. Gov. Josh Shapiro echoed this sentiment. “We do not want China to beat us in the AI race.”

Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick alleged that opposition to the AI revolution based on environmental concerns may be the result of Chinese manipulation. “The number one investor in the environmental narrative is China,” he claimed. “China … is trying to get us to close a coal plant a week.”

Some speakers were even more hawkish.

Rick Perry, former secretary of energy and former governor of Texas, praised President Donald Trump for acknowledging the “war that we’re in, and our war with the communist Chinese. That’s what this is all about, don’t get confused.”

Some experts on U.S.-China relations caution against such a blanket assumption of hostility.

“I worry about the feedback loop of fear and escalation, which I think can quickly spiral out of control,” said Kyle Chan, a researcher on industrial policy for the RAND institute and a post-doctoral researcher at Princeton University, in an interview with Public Source. Chan is currently writing a book about China’s tech-industrial policy. “I think words matter here a lot.”

He expressed hope for a more productive technological competition between the two nations, particularly in the field of AI, but he points out that “uncertainty over visa and immigration policies, and targeted attacks on some of the country’s most prestigious universities have sent a chill among foreign researchers in the U.S.”

Illah Nourbakhsh is a professor of robotics at Carnegie Mellon University and co-director of the Community Robotics, Education and Technology Empowerment Lab. (Photo courtesy of Illah Nourbakhsh)

Illah Nourbakhsh is a professor of robotics at Carnegie Mellon University and co-director of the Community Robotics, Education and Technology Empowerment Lab. (Photo courtesy of Illah Nourbakhsh)

Illah Nourbakhsh, a robotics professor at CMU and executive director of the Pittsburgh-based Center for Shared Prosperity, pointed out how a political environment that fails to welcome foreign talent may also hinder innovation. “The foreign and national students in our country are all outstanding. If we fail to encourage one group to innovate here, then we lose the chance of their innovations here.”

Nourbakhsh said the current climate reminds him of the first Trump administration, when “we started seeing more and more of our excellent students think about, ‘Should I set up that startup company here? Get a job at a university here? Or should I go to Europe? Or should I go back to a developing country where I come from perhaps, where the opportunities are sparser but I know I’ll be welcome?’”

William Curvan is a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer and can be reached at willcurvan@gmail.com. This story was fact-checked by Elizabeth Szeto.