The conference room at Pittsburgh Water‘s Penn Avenue headquarters filled up on a Friday morning in late September. Five board members sat around the long table: Vice Chair Erika Strassburger presiding, with BJ Leber, Michael Domach, Margaret McCormick Barron and Jamil Bey. Chair Alex Sciulli was absent.

Also missing over the course of that meeting, like every other meeting of the powerful board over the past 24 meetings across two years: A single no vote.

Rows of chairs behind the board members were occupied almost entirely by Pittsburgh Water staff: engineers, operations managers, finance directors, technology specialists. The audience was dominated by the utility’s own employees. No members of the public signed up to speak.

The meeting began at 10 a.m. Engineering presented updates on surface restoration programs and water reliability projects. Around 24 minutes in, operations staff reported on valve maintenance initiatives and drinking water quality: 2,217 water quality analyses conducted in August. The CEO recognized employees with excellence awards.

Then came seven resolutions, including spending authorizations and funding applications ranging from $492,000 to $29 million. A few generated brief questions: “Is this a loan or a grant?” “Does this expand security officers?” The answers were technical, brief.

All seven resolutions passed unanimously. The meeting adjourned after 54 minutes.

This is the oversight process at a utility that is in the midst of a billion-dollar capital program and seeking a sharp rate increase.

The Pittsburgh Water board votes on a resolution during its meeting on Nov. 21, as around 15 audience members observe. The board approved six resolutions during the meeting. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

The Pittsburgh Water board votes on a resolution during its meeting on Nov. 21, as around 15 audience members observe. The board approved six resolutions during the meeting. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Between October 2023 and September 2025, the board voted on 228 resolutions. The board voted unanimously on 223 of those. The other five included abstentions, but no nays. Meeting minutes show more than two-thirds of those resolutions were approved without questions. The votes authorized more than $870 million in spending.

Research on governance and board dynamics shows that prolonged unanimity can mean a lack of meaningful oversight, and can dampen public involvement. In the case of the Pittsburgh Water board, the unanimity streak comes amid decisions that will affect the wallets of thousands of households.

The board’s unanimous voting pattern comes as Pittsburgh Water seeks a two-year rate increase totaling around $35 per month for residential customers by 2027. The utility filed its rate case with the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission on June 4. The PUC’s decision is due March 8. Despite the stakes, only five of 24 board meetings had any public speakers. A total of 10 residents addressed the board over two years.

Pittsburgh Water board Chair Alex Sciulli speaks during the board meeting on Nov. 21. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Pittsburgh Water board Chair Alex Sciulli speaks during the board meeting on Nov. 21. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Sciulli told Public Source that board members “ask questions all the time and will request additional information often. Questions often arise around the need for a project, the cost, the risk of deferring and the benefit.”

Some of that, though, appears to occur at executive sessions, which are closed to the public.

“Board members are rate payers,” Sciulli said. “Their decisions and votes on resolutions are part of the public record, and they are accountable to their families, friends, to themselves and to the general public to make the best decisions for ratepayers.”

Why a long streak of yes votes can be a red flag

Pittsburgh Water serves around half a million ratepayers in the city and a few adjacent neighborhoods, delivering water, conveying sewerage or both, depending on the area. It is one of thousands of municipal authorities across Pennsylvania, all created to finance and operate public projects or functions.

The eight-member Pittsburgh Water board is appointed by the mayor and confirmed by City Council. Terms are five years, and the unpaid role involves approving budgets and expenditures and directing improvement initiatives.

Meeting minutes analyzed by Public Source show board members raised questions on 72 of the 228 resolutions. The remaining resolutions, nearly two-thirds, passed without any indication of discussion.

Pittsburgh Water CEO Will Pickering said the meeting minutes don’t capture the full picture of board engagement. “Board members frequently ask well-informed questions on record,” Pickering said. “The consensus is most likely driven by consistent education, tenured board members who understand ongoing projects, and informational discussions prior to the public meeting.”

Pittsburgh Water Chief Executive Officer Will Pickering speaks during the agency’s board meeting on Nov. 21. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Pittsburgh Water Chief Executive Officer Will Pickering speaks during the agency’s board meeting on Nov. 21. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

A longtime observer of the board sees the dynamic differently.

Myron Arnowitt, Pennsylvania state director for Clean Water Action, who has tracked Pittsburgh Water since the 2017 lead crisis, noted that while unanimous votes don’t necessarily indicate a problem, they can be a warning sign. “When there is political capture, [unanimous votes are] one of the results,” he said. “The system’s being run by an entity that’s outside of the actual agency.”

A 2023 Kennesaw State University analysis examining board voting patterns found that prolonged unanimity, combined with approval of questionable decisions, can indicate a “rubber stamp board” that fails to provide meaningful oversight.

The Kennesaw researchers analyzed Enron, the energy company that collapsed into bankruptcy in 2001 after widespread accounting fraud, costing investors billions and leading to landmark corporate governance reforms. Enron’s board approved 99.5% of resolutions unanimously despite multiple questionable transactions that ultimately led to the company’s demise.

Vincent Warther, a finance researcher who studied board voting patterns for the Journal of Corporate Finance, found that “votes are usually unanimous in favor of management.”

Organizational psychologist Jeremy Winget, analyzing group decision-making research, found that “systems designed for consensus can unintentionally hide insight. They reduce friction but also filter out the unusual, the dissenting and the diagnostic.”

Limited public participation as rates set to rise

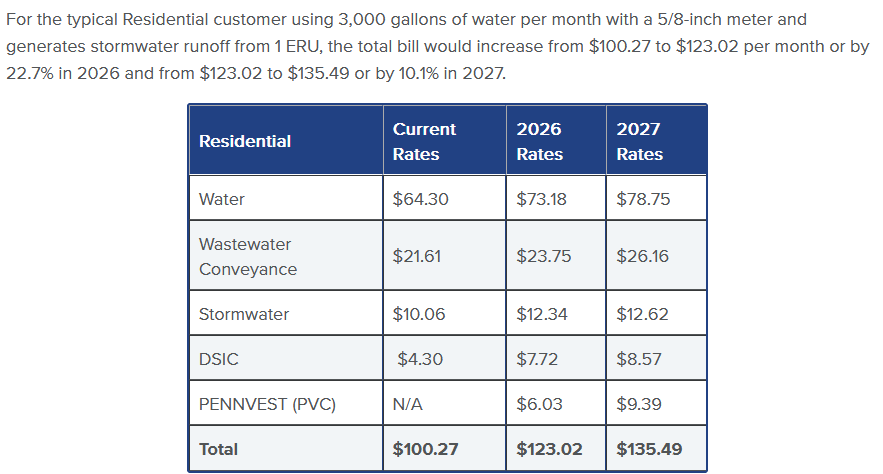

Pittsburgh Water’s requested rate increases, if approved by the PUC, would raise the average household’s combined water and sewer bill from about $100 per month to $135 by 2027.

Breakdown of the proposed Pittsburgh Water rate increases. DSIC is a distribution system improvement charge and PENNVEST is a state-run low-interest loan program. Source: Pittsburgh Water website.

Breakdown of the proposed Pittsburgh Water rate increases. DSIC is a distribution system improvement charge and PENNVEST is a state-run low-interest loan program. Source: Pittsburgh Water website.

Pittsburgh Water has a customer assistance program for households of modest means. It enrolled around 8,000 customers in 2024. With approximately 56,000 Pittsburgh residents in poverty, thousands of households potentially remain unenrolled despite facing water bills that exceed affordability thresholds.

The board has expanded customer assistance programs that now serve households earning up to 200% of the poverty level, Strassburger said, with staff who have social work backgrounds actively marketing the programs at community meetings and festivals.

Pickering said Pittsburgh Water “hosted or participated in nearly 60 community events or meetings” through October 2025, addressing “questions associated with construction projects, investment of ratepayer dollars, water quality and safety and customer assistance programs.”

The PUC has also held lightly attended public meetings on the rate increase.

Following the emergency part of the COVID-19 pandemic, some city and county boards were slow to return to in-person meetings, despite legal requirements that they do so. Pittsburgh Water, though, was a relatively early adopter of hybrid transparency. It livestreams board meetings and posts recordings online — transparency measures implemented after the lead crisis. The board’s October meeting had 99 views on YouTube by mid-November.

Linnea Warren May, a policy researcher at the RAND Corporation who studied Pittsburgh Water’s lead remediation options in 2017 and researches water utility governance, said “meaningful public participation requires that community input influences decisions.”

Between October 2023 and September 2025, the board voted on 228 resolutions. The board voted unanimously on 223 of those.

Meaningful participation, Warren May said, “sometimes involves humility on the part of the utility saying, ‘We were planning to do this, but you told us this, so we changed our mind and now we’re doing it this way.’”

Research in water governance suggests that even the technical nature of water infrastructure decisions benefits from extensive public engagement. A 2021 study of Brazilian water systems found that technocratic approaches that limit public participation can reduce long-term resilience, even when technical expertise is sound. The study showed that systems relying primarily on private expert deliberation “failed both to insulate decisions from politics and to explore adaptive water management solutions.”

Board deliberation happens privately

Pittsburgh Water board members say substantive deliberation does occur, but much of it happens outside public view in executive sessions and Executive Committee meetings before each monthly meeting.

Strassburger said resolutions that reach the public agenda have typically been vetted through multiple prior discussions. She said the board spends “at the very least an hour-long executive session” taking a “deeper dive” into the same topics raised in other, open meetings.

Pittsburgh Councilor Erika Strassburger looks to a TV screen during a hearing in the City-County Building on Sept. 10. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Pittsburgh Councilor Erika Strassburger looks to a TV screen during a hearing in the City-County Building on Sept. 10. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Materials are shared in the board’s online portal ahead of meetings, allowing members to prepare questions for Executive Committee sessions and executive sessions.

Sciulli, the chair, wrote in response to questions that “Effective board deliberation starts with transparent communication and full disclosure of pertinent information and issues, and then providing the opportunity and the forum for questions, feedback and discussion.” The Executive Committee — comprising the board chair, vice chair and treasurer — meets bi-weekly with the CEO and executive leadership, Sciulli wrote. Board committees meet regularly with staff on topics including water quality, stormwater, safety and security, environmental compliance and ethics and financial matters. Board education sessions are organized on topics such as annual budgets and regulatory compliance.

“What we end up voting on is fairly uncontroversial,” Strassburger said. “If you look at it, it’s spending on the contractor that was chosen for the lead replacement … the contractor that was chosen to do all the paving work for that following year.” For most resolutions “there wouldn’t be much reason for discussion.”

Sunshine on the water

Enacted in 1986, Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act requires public bodies to deliberate and make decisions in open, public meetings.

The act permits executive sessions for specific purposes: personnel matters, litigation, real estate negotiations, labor relations, public safety and investigations. But the act prohibits using executive sessions “as a subterfuge to defeat the purposes” of the open meetings requirement.

Strassburger said the board’s executive sessions often include legal and personnel issues, but added that more mundane discussions also occur. “Occasionally, a board member will have a question about a board resolution up for a vote that day. This executive session offers a place to discuss concerns or answer questions before the board meeting. Best practice is to repeat the question and respond publicly to daylight that discussion, and I will take it upon myself to change it and recommend it to fellow board members.”

Arnowitt said timing and transparency are key concerns regarding these private sessions. “When agencies use executive session, they need to be clear about what the purpose is,” he said.

“If no one’s really asking a lot of questions, then they probably don’t really know what’s actually happening.”Myron arnowitt

Melissa Melewsky, media law counsel for the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association (PNA), said Pittsburgh Water’s practice of deliberating in executive sessions before public meetings raises legal concerns.

“That’s not the way the Sunshine Act is supposed to work,” Melewsky said in an interview. There’s nothing in the law “that allows public officials to essentially have the public meeting before they have the public meeting.”

Melewsky said when agencies treat public meetings as “largely pro forma” with no substantive deliberation, “that is a red flag that deliberation is happening outside the public meeting where it’s not supposed to happen.”

The public needs to witness deliberation to understand government decisions, Melewsky said. “It’s the deliberation that tells us what details are being considered, what details are not, who’s voting which way and why.” If that’s not happening in public, she said, it’s a problem.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in the 2013 case Smith v. Township of Richmond that closed-door gatherings are permissible “solely for the purpose of collecting information or educating agency members” if they “did not involve deliberations.”

Melewsky said agencies often defend closed-door discussions as “information gathering” rather than deliberation. “But the problem is, what that devolves into is deliberation. … Once that information is shared amongst and discussed amongst the board, that crosses the line.”

PNA’s guide to the Sunshine Act identifies “insignificant and very rarely imposed” penalties as undermining the law. “Worse, the Pennsylvania courts have repeatedly permitted public agencies to ignore the act’s requirements by holding that agencies can ‘cure’ Sunshine Act violations” by re-voting in public.

Strassburger acknowledged room for improvement, pointing to the example of former board member Jim Turner. “He was brilliant at asking the same question that he had either asked over email or in executive session in the public forum … to highlight what has already been discussed. So there’s no question about what was discussed.”

Pittsburgh Water Chief Environmental Compliance and Ethics Officer Frank Sidari speaks during the Pittsburgh Water board meeting on Nov. 21. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Pittsburgh Water Chief Environmental Compliance and Ethics Officer Frank Sidari speaks during the Pittsburgh Water board meeting on Nov. 21. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

She said board members should follow Turner’s example more consistently. “Once we’ve discussed it, we don’t want to grandstand, but we could be better about daylighting some of the hard discussions we have internally … I’ll own that, and we should all own that.”

Strassburger also pointed to governance improvements Pittsburgh Water has made since the lead crisis. She highlighted the creation of an environmental compliance and ethics position filled by Frank Sidari.

Strassburger said Sidari has created a culture of whistleblower protection and open discussion of ethics “if you’re not sure about anything, whether it is a gift that you received around Christmas time from an engineering firm … or a dinner you got invited to” or federal environmental reporting rules. “Everything is reported, no shaming, no wrong answers.”

Improving public engagement

Pickering said Pittsburgh Water’s board meetings show “open discussion at a higher level and for a longer period than our peers.” He pointed to the utility’s accessible hybrid meetings, which were “commended by Public Source as being more transparent than our peers” in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County.

Warren May said comparing transparency practices across different boards requires looking at similar size, governance structures, and whether their data is publicly accessible.

RAND identified Niagara Falls Water Board in New York as one peer of Pittsburgh Water. At an April 28 meeting of the Niagara board, an employee evaluation policy failed 2-2. The board revised it during the meeting based on member concerns, after which it passed 3-2 after documented debate. The meeting ran 161 minutes.

Melewsky said measures like livestreamed board meetings, while valuable, don’t substitute for the Sunshine Act’s core requirement.

“It doesn’t say, ‘if you put your minutes online, you don’t have to have public deliberation,’” Melewsky said. “That’s not the way the law works.”

Melewsky said public agencies struggling with transparency can access training by the Pennsylvania Office of Open Records or guidance from the PNA.

When Penn State University’s board of trustees faced a lawsuit over similar closed-door practices, she noted, the settlement required annual Sunshine Act training for board members.

Pittsburgh Water has worked to rebuild public confidence since the 2017 lead crisis, when the utility failed to properly treat water and notify affected residents. RAND’s Warren May said utilities can face obstacles when trying to restore trust.

Arnowitt said the stakes are high for Pittsburgh Water’s half-million ratepayers. “If no one’s really asking a lot of questions, then they probably don’t really know what’s actually happening,” Arnowitt said, adding that this lack of oversight means the public also remains uninformed.

Brian Nuckols is an investigative journalist based in Pittsburgh. His reporting focuses on U.S. politics, local government and technology, with a particular interest in how powerful institutions shape the lives of vulnerable communities. His work has appeared in The Lever, Public Source, Jacobin and Pirate Wires. He can be reached at brianjnuckols@gmail.com or on X at @briannuckols13.

This story was fact-checked by Tory Basile and Rich Lord.

RELATED STORIES

Keep stories like this coming with a MATCHED gift.

Have you learned something new today? Consider supporting our work with a donation. Until Dec. 31, our generous local match pool supporters will match your new monthly donation 12 times or double your one-time gift.

We take pride in serving our community by delivering accurate, timely, and impactful journalism without paywalls, but with rising costs for the resources needed to produce our top-quality journalism, every reader contribution matters. It takes a lot of resources to produce this work, from compensating our staff, to the technology that brings it to you, to fact-checking every line, and much more.

Your donation to our nonprofit newsroom helps ensure that everyone in Allegheny County can stay informed about the decisions and events that impact their lives. Thank you for your support!

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.