By 1903 Moravian Bishop Joseph Levering had begun work on a long-planned project. Establishing himself in Nazareth’s Whitefield House, a space long associated with the church, he was getting to work on his monumental project, the history of the Moravians in Bethlehem and the development beyond their era to a secular, industrial city. It was a huge undertaking but one Levering had embraced with enthusiasm.

Whitefield House, Nazareth

Moravian History Museum

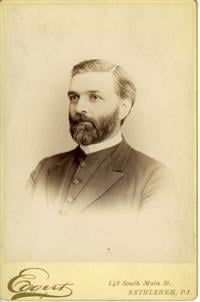

Levering had first seen the light of day in Harrisburg in 1849. His family were among those following the tide of migration and settlement that pushed west. By 1859 they had settled in Illinois, and the 10-year-old was studying the roots of the faith that would guide his later life. Eleven years later he had entered Moravian College and Theological Seminary.

As the 1870s moved on, Levering also moved on to congregations in Ohio and Wisconsin with his wife Martha Whitesell and eventually his daughters. They arrived in Bethlehem in September of 1888 where Levering was named a bishop. Here he also was asked and agreed to take up the task of Provincial Archivist. Perhaps it was here that he first envisioned his project.

With the dawn of the 20th century and needing what he thought of as a rest, he began to research and write his monumental tome “A History of Bethlehem,” a foundation of scholarship to which others have since added. At the time of his passing in April of 1908 at the age of 59, his papers and his research were collected and eventually deposited with the Moravian Archives. In 2007 they were organized by Moravian College student Michael Tier. It can also be found online.

From “A History of Bethlehem,” by Bishop Levering

Levering, in his preface, points out that what he had hoped he had given is the true view of life in Moravian times. “Correct historical information has never been entirely lacking and has increased as the years go on,” he notes. But that some things had led to the misconceptions of Moravians and their ways of have been “propagated and erroneous views by newspapers have been hard to eradicate from the popular mind…most unreal elements of these diversified views have the firmest hold on the public.”

Levering goes on to note that he has used the most important primary sources: manuscripts, diaries, official minutes, synodical records, personal records and correspondence. He also includes what he calls “miscellaneous,” newspapers and other publications.

Levering’s purpose is clear. He is trying to recount not just the history of Bethlehem itself but the evolution of it from a religious community with roots in German-speaking Europe by the pious charismatic figure Count von Zinzendorf. It had transformed from the New World colony of Pennsylvania, a place of refuge for a unique religious society, to an American community true to those roots and at the same time trying to share in the national ideals shaping the culture around it.

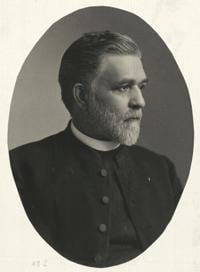

Bishop Thomas Levering

Moravian Archives, Bethlehem

As a historian, Levering’s work may be off-putting for some. For one thing he clearly feels as a devout Moravian the uniqueness of his sect’s Christian community. On the other hand, he recognizes the importance of how the role of the American experience shaped it and became reflected by it. The “city on a hill” ideal created by New England’s Puritan divines was clearly a part of it.

Writing, Levering begins with the history of the sect’s early years coming out of post-Reformation Central Europe. Persecuted by Catholics and other Protestant faiths and reduced in the early 18th century to a few members, they were transformed by the intervention of Zinzendorf’s efforts into a thriving community in William Penn’s colony of religious refuge, drawing the attention of many in Europe.

By the time of the American Revolution, Bethlehem was regarded by some Enlightenment figures, both religious and non-religious, as an example of what a peaceful community should be. Their outreach to Native Americans, which infuriated many colonists who saw them as collaborators with their ultimate enemy, clearly won many in Europe as friends of Roseau’s Noble Savage.

Engraving depicting the baptism of Indian converts by Moravian missionaries in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, around 1757

Courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia

But as decimated tribes were forced off their lands, the “missionary impulse” gradually faded for Bethlehem’s Moravian community. By the end of the 18th century, they were an outgrowth of a church in Europe who could no longer afford to support them. And as Levring skillfully points out, they were forced to change, sell and sometimes abandon the social efforts that seemed the heart of the Moravian mission.

Perhaps the most interesting part of Levering’s history is the change of the Moravian Church and Bethlehem from about 1824 to 1860. He presents the changes in those years as slow at first and then rapidly gaining speed. Older members of the church hierarchy see a rising tide of opposition first to certain long held practices in worship.

Younger Moravians, looking to the outside world, look toward a growing America and believe they are old-fashioned, holding them and the community back. It was happening of course in many places, but Levering’s writing gives a particularly Moravian slant to them. He was a child and grew up in the Midwest, far from where this was going on. Some would say this would make him more objective, others that it made him more dependent on the memories of others and thus could not truly understand what it was like. Whatever it was Levering’s prose seems to lay it out clearly so that even non-Moravians could understand it.

As it was in many places across the country, the Panic of 1837 brought a hole in the false, highflying inflated prosperity of the time. Moravians with deep roots in the community like Owen Rice III were wiped out and became pariahs in the community. When the revival came it came from outside the community from Connecticut Yankee Asa Packer and Robert Sayre from the coal regions.

It happened on the south side of the Lehigh that the Moravians had largely used as a cattle range, that the new prosperity of zinc, iron and steel gave Bethlehem its future identity. In the words of one local historian, they found the Moravians an interesting, “quaint” relic of the past, out of touch with the industrial present of the 20th century.

Bishop Thomas Levering

Moravian Archives, Bethlehem

Those looking for a copy of Levering’s book can find it largely on reference shelves and there are many writers since then who have explored in great depth many aspects of Bethlehem history. But it can be argued that Levering’s pioneering study deserves respect as the first.