This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

The world uses billions of tons of concrete every year. Concrete production is a big contributor to climate change, making up about 8% of global carbon emissions each year.

Researchers around the world are working to find ways to make concrete greener, including at the University of Pennsylvania, where teams are 3D printing streamlined concrete forms and developing alternative concrete mixtures that absorb more carbon from the air.

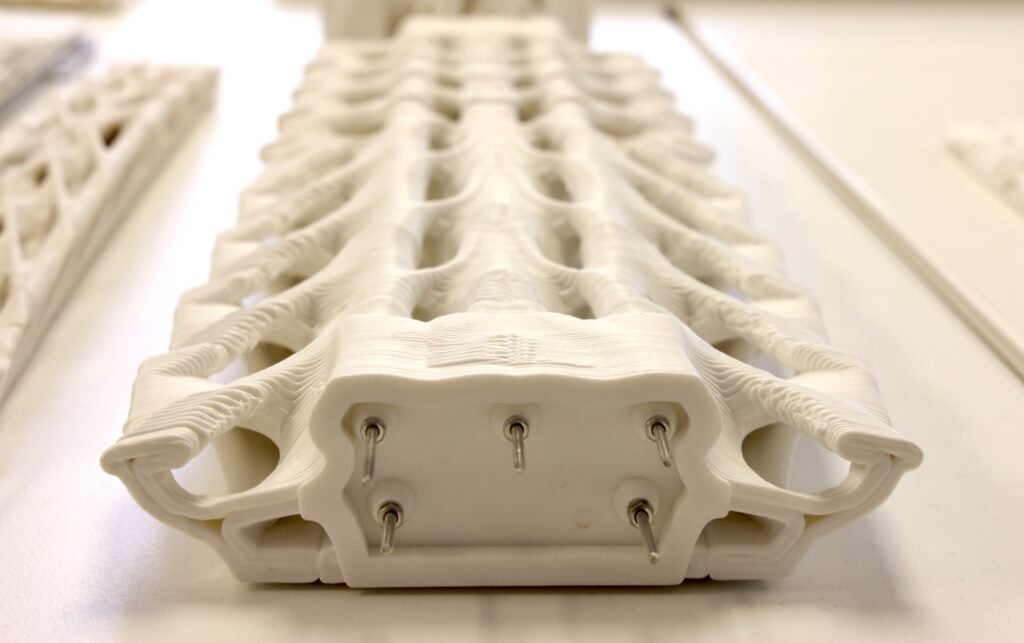

Streamlined 3D-printed concrete sections reduce the need for steel reinforcement inside the concrete. Instead, steel cables, which are easier to remove during demolition, are stretched inside thin tunnels in the concrete sections. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Streamlined 3D-printed concrete sections reduce the need for steel reinforcement inside the concrete. Instead, steel cables, which are easier to remove during demolition, are stretched inside thin tunnels in the concrete sections. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

“Anything we can do to reduce emissions from the building sector is going to combat global temperature rise and climate change,” said Ryan Welch, a principal and research director at the Philadelphia architecture and planning firm KieranTimberlake, who estimated the emissions associated with the Penn researchers’ designs.

Optimizing shapes to use less concrete

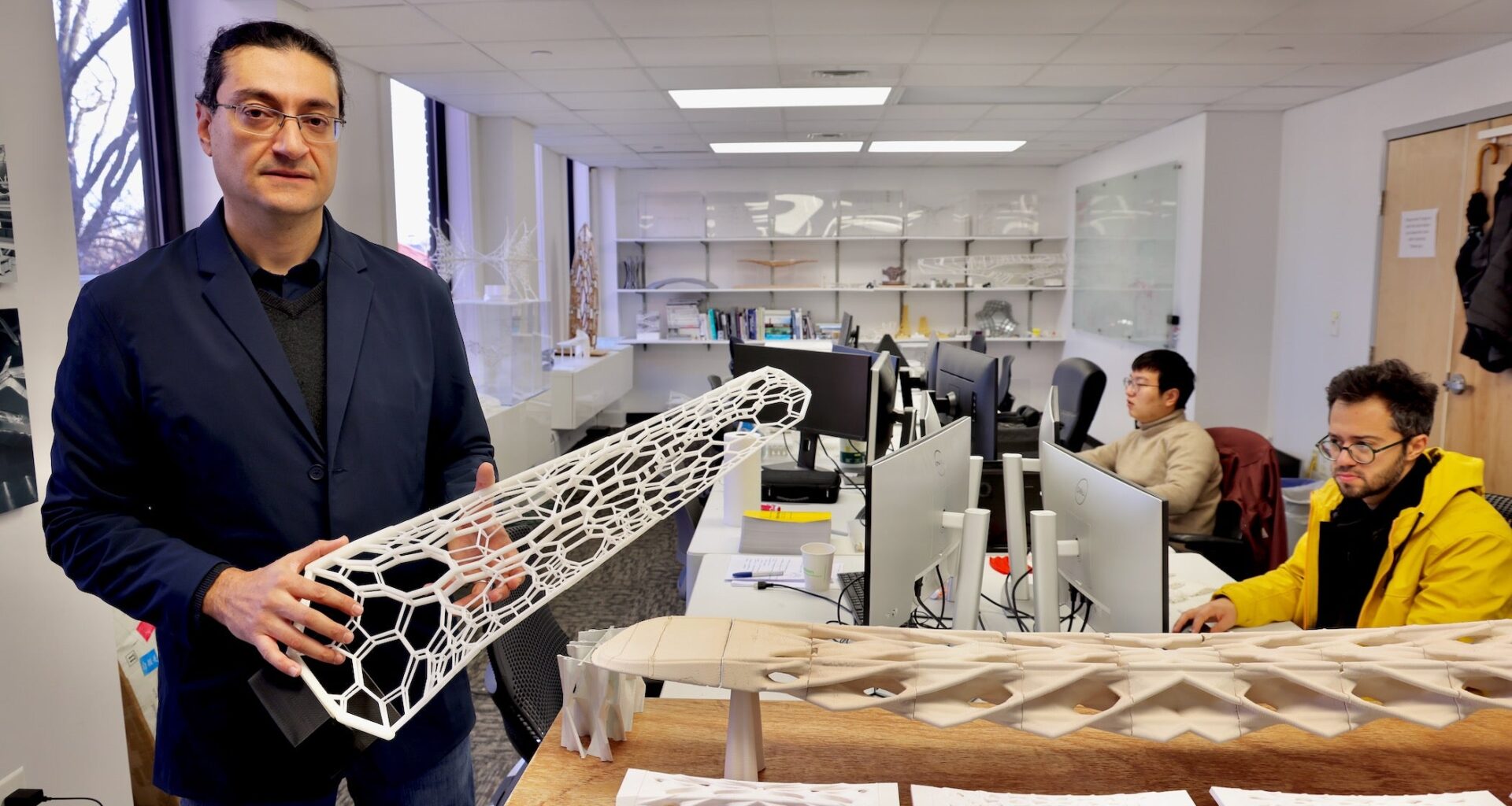

Masoud Akbarzadeh, a professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, is working with students to design concrete structures that use as little concrete as possible while remaining strong.

“In order to reduce the carbon footprint, you need to reduce the use of material that would last through the life cycle of a building,” Akbarzadeh said.

Akbarzadeh’s team models the flow of forces through a structure, such as a bridge, floor, beam or column. They then design a concrete form that bears weight most efficiently, capitalizing on concrete’s strength, which is compression.

“[The force is] just pressing against the cross section, always, all the time,” said Akbarzadeh. “That’s allowing you to take advantage of the entire cross section of your material, and you can remove … excessive material from this, so it becomes super lightweight, but in the meantime takes a lot of force.”

Masoud Akbarzadeh, director of the Polyhedral Structures Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania, stands beside a structure made of 3D-printed concrete, which is lighter, uses less material, absorbs more carbon and recycles more easily than conventional concrete. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Masoud Akbarzadeh, director of the Polyhedral Structures Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania, stands beside a structure made of 3D-printed concrete, which is lighter, uses less material, absorbs more carbon and recycles more easily than conventional concrete. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A concrete pavilion built outside the Pennovation Center in South Philadelphia demonstrates this technology. The ceiling is organic-looking, hollowed out with rounded voids and caverns not typically seen in building architecture.

“If you look at natural structures, they’re actually full of these cavities,” Akbarzadeh said.

It would be difficult to create these complex structures by pouring concrete into a mold, Akbarzadeh said. Instead, his team 3D prints the structures in pieces, then assembles them on site.

Akbarzadeh said minimizing concrete use is not the only way that 3D printing reduces emissions. Printing, rather than pouring, sections of concrete buildings eliminates the need for concrete forms. It can also reduce the need for steel reinforcement inside the concrete, he said. Akbarzadeh’s structures do include some steel cables, but they are stretched inside thin tunnels in the concrete, rather than embedded in the concrete itself, making them easier to remove during demolition.

“We don’t have the conventional cages of rebars that could go within the concrete that makes it really difficult to recycle down the road,” he said.

Akbarzadeh said his team’s designs could be used to print floors of buildings or bridges.