Marketing materials for the Ryley Apartments in the Ludlow neighborhood of North Philly describe the property as an “exciting residential community” where residents can enjoy “a dynamic urban setting” and “high-end living.” But for Melissa Mont, securing an apartment in the building meant something much more essential: escaping a slumlord and being able to afford rent, which was important given that she is disabled and lives on a fixed income. So, when the building’s property management company asked her to sign an addendum to pay a $30 monthly amenity fee, Mont balked.

Listen to the audio edition here:

“There are no amenities,” she says, adding that when she asked the management company what the fee was for, they said to cover the cost of software that provides access to the keyless building.

But the amenity fee simply added to the other fees she was being charged for water, sewer and trash, bringing the total to about $60 a month, or $720 in additional annual costs. “That doesn’t seem like a lot, but when you’re on a fixed income, that’s huge, especially when you didn’t know you were going to get hit with it,” Mont says.

The building’s management company didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Mont, 51, is experiencing what a lot of the city’s hundreds of thousands of renters — renters comprise half of all Philadelphia residents — deal with when leasing from mostly large landlords: “junk fees” that may or may not be listed on a lease and are in addition to monthly rent. A fee for trash. A fee for parking. A fee for sweet pup Charlie. A fee for water. A fee for the common area that goes unused. A fee if you don’t pay for rent through the landlord’s online portal, which also charges a processing fee. And if renters don’t pay the fee on time? There may be a late fee for that, too.

In a city where affordable housing is scarce, most renters just swallow junk fees as a cost of living expense. Some of these fees may be listed on the initial lease; some aren’t mentioned until they show up on bills; and others are added during the tenancy. Sometimes the fees fluctuate from month to month, making it difficult to budget ahead.

Junk fees have become so routine, hardly anyone thinks about them. But these fees aren’t just a nuisance. Housing advocates say they can add to the financial burden of renters who are already struggling to live within razor-thin housing budgets — a burden that places tenants at risk of losing the roofs over their heads. And while some fees cover hard costs — for instance, application fees that cover tenant screening or deposits for pets — they can be misleading, increase unexpectedly or may be excessively high for the service being covered.

“Junk fees hide the true cost of rental housing, making it tough to compare prices and leading to difficulty paying for undisclosed housing costs,” says April Kuehnhoff, a senior attorney at the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC), in an email. “Ultimately, families might have to move due to deceptive pricing or even face eviction when they fall behind on the rent due to accumulating junk fees.”

More than 20 states and several local governments have enacted laws to bring transparency to rental fees, according to a recently updated report on junk fees from NCLC. The organization also identified 27 different fees commonly charged to renters, including many of those that Philadelphia renters have experienced.

“In a city facing an affordability crisis, landlords should be part of the solution by clearly communicating the true cost of living in their properties. — Rue Landau, Philadelphia City Council

Philly has taken a step towards regulating these fees. One year ago, City Council passed Councilmember Rue Landau’s legislation that capped the cost of a rental application at $50 or the fee of a background check, whichever is less, per applicant/landlord in a 12-month period. That same legislation allowed that a prospective renter could be charged only once per property (for buildings with multiple units) and, importantly, that new renters could pay security deposits in monthly installments, instead of all upfront. Landau, who had support from Councilmembers Kendra Brooks, Nicolas O’Rourke and Jamie Gauthier, called the legislation “MAP” for “Move In Affordability Plan.”

But there’s work to be done yet.

The Homeowners’ Association of Philadelphia (HAPCO), which represents many landlords, lobbied to increase Landau’s proposed application fee from $20 to $50. The organization has said it was responsible for quashing a provision that would have allowed renters to submit their own background check from the previous 30 days — a provision that would have allowed people putting in multiple applications for different apartments to save on multiple fees.

HAPCO didn’t respond to requests for comment on their position.

The application cap, though, could be just the first step in the war on junk fees in a city where the median rent for an apartment is $1,865 and nearly a third of renters pay a heavy chunk of their income each month. Other cities, from Denver, Colorado, to Akron, Ohio, have enacted some form of regulation, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. One of those jurisdictions is Seattle, Washington.

Seattle’s fight against junk fees

Rents in Philadelphians have doubtless risen, but the situation could be far worse. Just look at Seattle, where Big Tech companies like Microsoft and Amazon are headquartered and the average monthly rent for an apartment is $2,100, per Zillow — which housing activists describe as “unlivable.” As a partial result, Seattle consistently ranks as having one of the highest averages of homelessness among big cities.

“If you don’t make six figures, it is really difficult to find an affordable place to live in the city,” wrote Guy Oron for Real Change, a publication that says it represents people struggling to make ends meet or experiencing homelessness in Seattle.

On top of Seattle’s crushing monthly rent costs, tenants have also been battling junk fees going back as far as the 2000s — and sometimes winning. In 2004, the city created a Third-Party Billing Ordinance that regulates how landlords can pass on the costs of utilities to tenants. Common among large apartment buildings, where a master meter’s usage is divided up, in Seattle, landlords are required to disclose meter readings for sub-metered units, and tenants must be notified of any new billing changes. Tenants can file complaints with landlords; if there is a dispute, they can take their complaint to a city office that handles code enforcement or to small claims court.

For housing advocates, the most significant recent win came in 2023 when a law passed that capped application fees at $10 for a 12-month period and eliminated so-called “delivery notice fees” (fees of up to $100 imposed by landlords as a charge for notifying tenants of late fees).

Solid Ground is one of the housing organizations that backed the 2023 law. Phoenica Zhang, a Solid Ground community policy specialist, says these fees are pernicious because they saddle tenants with debt that is nearly impossible to pay back.

“These are folks who are struggling and more likely to have late fees, and least likely to pay the fees as well,” she says, adding that there was a sense that the late fees were punitive. “It was seen as a way for landlords to kind of evict over time.”

Zhang says according to her organization’s tenant counselors, renters rarely know about protections that could control costs. “It’s really self-enforcement,” she says. “You as a tenant have to bring the case forward. You have to know about these ordinances.”

But she adds that the organization’s tenant light has been receiving fewer complaints about late fees since an ordinance was passed that caps them at $10 a month.

“The few complaints we have received were from folks who recently moved here to the area and wanted to verify what they have heard from others about late fee limits,” Zhang wrote in a follow-up email. The effectiveness of the ordinance can be seen in surrounding areas where similar laws don’t exist. “Landlords are still charging exorbitant fees.”

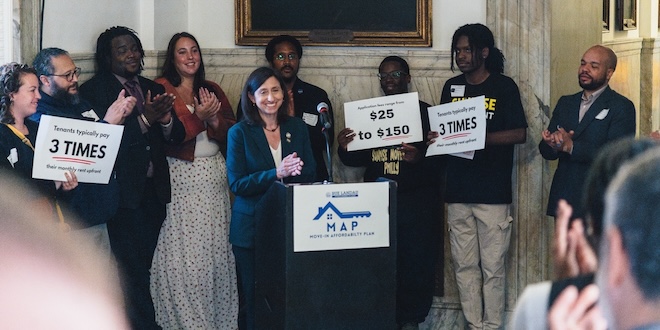

Philadelphia City Council At-Large member Rue Landau (center) celebrates the passage of the Move-In Affordability Plan “MAP” in City Hall. Photo by Ta’Liyah Thomas for PHL Council. Junk fees for … an indoor pool?

Philadelphia City Council At-Large member Rue Landau (center) celebrates the passage of the Move-In Affordability Plan “MAP” in City Hall. Photo by Ta’Liyah Thomas for PHL Council. Junk fees for … an indoor pool?

Alden Park Tenants Association President Kadi Ashby, who has lived at the “Luxury Apartments” in East Falls for about two-and-a-half years, pays a monthly amenity fee ($40), along with monthly fees for pest control ($5), trash ($20), water and sewer ($49) and for a third-party service that handles the billing ($8). That’s a total of $122 a month in fees, nearly $1,500 per year.

The water usage fees also cover the building’s indoor pool, she says, “Sometimes it will be double what it usually is. We don’t get an explanation as to why.”

Ashby says some of her neighbors in the building are paying much more. But again, it’s unclear why. “Some people say they have the same layout as the people above and below them but they’re not paying the same amount,” she says.

She is currently fighting the management company for refusing to renew her lease and has filed a complaint with the Fair Housing Commission.

L3C Capital Partners, the complex’s property management company, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

At-Large Councilmember Rue Landau, a former housing lawyer and activist who championed the rental application fee cap, says she had witnessed how junk fees can add up to $100 or $200 in monthly expenses for renters and would support a rental transparency bill. “Renters deserve to know the full cost of living before they commit to a lease,” she wrote in an email. Landau’s move-in affordability plan was a first step, she says. Now, her office is looking into what changes the City can make to protect tenants from other junk fees. “Transparency is essential to help renters make informed decisions and avoid being blindsided.”

Meanwhile, she says, existing state and local laws need to be enforced more effectively to protect renters, arguing that, by law, leases must clearly state all costs, security deposits, habitability, and other costs. “In a city facing an affordability crisis, landlords should be part of the solution by clearly communicating the true cost of living in their properties,” she says.

Cristian Salazar is a longtime journalist and nonprofit communications expert in Philadelphia.

![]() MORE IDEAS WE SHOULD STEAL FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE IDEAS WE SHOULD STEAL FROM THE CITIZEN

Seattle Community Living. Photo by Bill Hinton, Getty.