Projects in South Side Slopes, Four Mile Run and others are now on hold. The projects would have helped reduce stormwater pollution and mitigate flooding.

“Stormwater projects in the City of Pittsburgh have been defunded almost across the board,” said Annie Quinn, director of the Mon Water Project, a local watershed group that supports Four Mile Run, a watershed that spans Schenley Park, Oakland, Hazelwood, Greenfield and Squirrel Hill.

Pittsburgh Water says it had to cut funding for stormwater projects like Four Mile Run, despite already having spent money on planning and design ($7.9 million before it was shelved at the end of 2024) so it can fund pump upgrades mandated by a consent decree. A consent decree is legally binding and lays out improvements required by state or federal government.

The utility has also continued to replace lead pipes, mandated under a previous consent decree.

“Pittsburgh Water is really protecting our customers through the delivery of safe and reliable water services,” said Rebecca Zito, senior manager at Pittsburgh Water’s public affairs office. “At the same time, though, we still have been able to remain committed to stormwater.”

Funding for capital projects in general is projected to drop as Pittsburgh Water focuses on existing and anticipated consent decrees. The utility is negotiating a new decree with the Environmental Protection Agency: a Wet Weather consent decree to comply with the Clean Water Act and Clean Streams Act.

“We’re strategically preparing ourselves for those additional requirements,” Finance Director Edward Barca said.

This year, stormwater projects received $29.5 million, but funding is set to decline each year. In 2029, stormwater will receive $169,014 according to the utility’s 2025-29 capital improvement plan, which allocates money for long-term investments five years at a time, often pertaining to infrastructure.

Floods, which have been made worse by wetter weather, development and aging infrastructure, are one of Pittsburgh’s most likely and damaging hazards, according to the 2025 city Emergency Operations Plan.

The Four Mile Run project would have fortified the low-lying areas of Greenfield, known as “the Run,” against sewage “geysers,” where sewage and stormwater shoot from manholes. This happens when rain overwhelms tunnels underneath the Run, generating water pressure intense enough to pop manhole covers, which fly into the street, trailed by a spout of sewage and stormwater.

Run resident Laura Vincent has seen geysers “as high as that building,” she said, pointing to a two-story building around the corner from her house.

“Typically, it’s more like 13 to 15 feet. But we have seen it at that height.”

Members of the Greenfield community who have dealt with flooding in the neighborhood. Flood levels have previously reached the top of the black fence behind them. Dec. 5, 2025

Members of the Greenfield community who have dealt with flooding in the neighborhood. Flood levels have previously reached the top of the black fence behind them. Dec. 5, 2025

The last time the geysers flooded streets and basements in the Run was 2021, Vincent said, when flood water — which sometimes swirls with toilet paper and dead rats — reached chest deep. After the water recedes, it leaves a smelly, dusty residue that permeates for weeks, according to Quinn and Vincent.

The utility said it has completed 23 stormwater projects since 2018 and is continuing to maintain related infrastructure, according to Zito. This includes two drainage channels to manage stormwater in Schenley Park, completed in 2020.

But according to the capital improvement plan, only six of the previous year’s 16 stormwater projects are set to move forward.

Projects with designs less than 90 percent complete, including Four Mile Run, “got shelved,” said Tony Igwe, wet weather program manager at Pittsburgh Water.

Barca said there is a possibility that the authority could secure outside funding to move forward with stormwater projects. But for now, residents will need to wait.

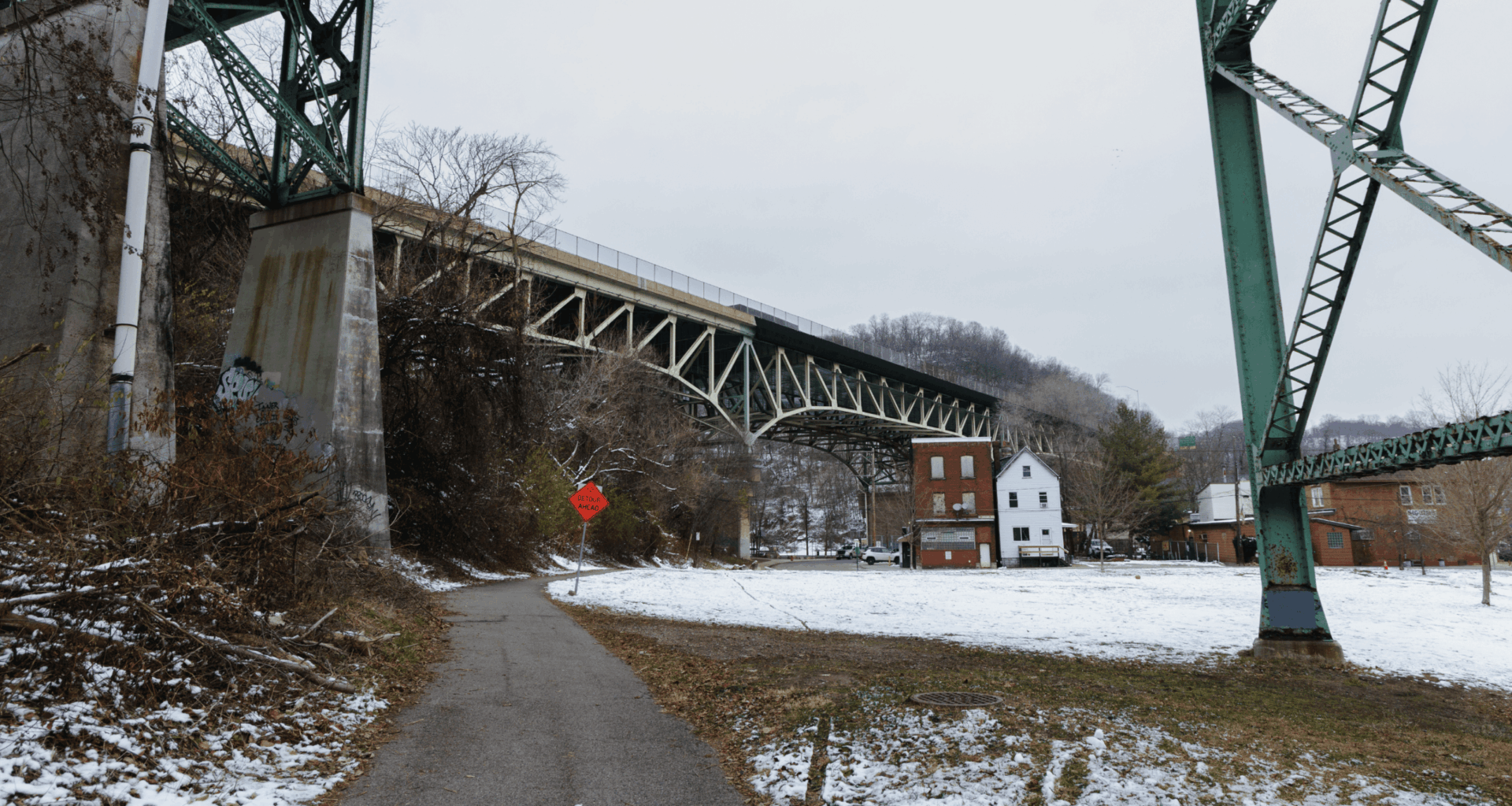

When Pittsburgh Water cut stormwater funding, it had knockoff effects for South Side Park, which sits at the intersection of three neighborhoods: South Side Slopes, South Side Flats and Arlington.

“It’s a terrible blow,” said Kitty Vagley, who is a volunteer board member and treasurer of Friends of South Side Park, a group dedicated to maintaining the nearly 60-acre piece of land, which she said had been neglected for decades. In 2018, the City of Pittsburgh Department of Urban Planning produced a South Side Park Master Plan. If implemented in full, the plan would have converted the swampy entrance into a wetland.

“The whole entrance to the park is now put on hold,” Vagley said. “It was going to be this beautiful entrance. A parking area, boardwalk, a small amphitheater that we people could have concerts in.”

At the Run in Greenfield, there have been some improvements, Vincent said. Pittsburgh Water fixed a faulty outflow, a piece of infrastructure that discharges water into the rivers.

Vincent said this has reduced the risk of flooding, but the threat has not been eliminated. She continues to come across manholes that spray and bubble during heavy rain — a warning sign that they might soon blow.

“It kind of looks like ‘shoo, shoo,’” Vincent said, making a spraying motion with her hands. “It is the way you would think of a whale spouting. It’s that little wisp of water.” Other times, when it bubbles, “it looks like boiling water,” she said.

She and her husband John said they have spent thousands of dollars on flood-related cleanup and improvements at their home and their wood shop around the corner.

“Luckily we were able to have the money to repair and do backflow valves, but a lot of people in this whole area down here, people don’t,” said John Vincent.

Hannah Frances Johansson is a reporter for the Pittsburgh Media Partnership newsroom. She holds a master’s degree from the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. She is a 2025 recipient of the Overseas Press Club Scholar Award and a former 11th Hour Food and Farming Fellow. Her reporting has appeared on CNN, Pittsburgh’s Public Source and Michigan Public Radio, among others. She resides in the city’s North Side. Reach her at hannah.johansson@pointpark.edu