In the university classroom, the sight of a laptop is ubiquitous, but as the spring semester begins, doubts surrounding technology use are resurfacing.

In the wake of state and national movements to limit technology such as cellphones during class hours, community members at Pitt are questioning the potential effectiveness of a screen ban in a higher educational setting.

Pitt students have previously cited becoming distracted by other students who use laptops for reasons other than schoolwork in the classroom. In December, the Educational Policies Committee debated whether a push for a University-wide ban on cellphones in the classroom would be a possible solution, citing issues like distraction and mental health concerns.

In K-12 classrooms across the U.S., schools are starting to lean towards stricter cellphone policies. In Pennsylvania, a December bill proposing a bell-to-bell phone ban across schools in the state was supported unanimously by the Senate Education Committee and will go to the State Senate for consideration.

Potential technological bans at the K-12 and university level would exclude disabled students with accommodations and English learners who use technology to translate. Though Pitt’s Educational Policies Committee did not reach an agreement on the ban in December, the consideration highlights larger questions in the community about technological distractions in class.

Some students, such as Rahitha Gopinathan, a junior bioengineering student, believe a screen ban would be ineffective despite the distractions in the classroom.

“I think that [phones in the classroom] can be a good thing because students can use their phones for TopHat or they might need to answer a text,” Gopinathan said. “They might need to use it for an emergency.”

Gopinathan also said phones can be useful for academic reasons, such as taking pictures of notes on the board while sitting far away.

“I don’t think a ban would be effective because people are going to find ways to use their phones, or their phones on their laptops,” Gopinathan said. “I don’t think a phone ban is effective at all.”

Connor Donovan, a graduate math student in his final semester, said his math classes have been mostly technology-free. Though he said there are pros to technology, such as following along to the lecture with notes, students often benefit from a screen-free environment.

“I’m also a T[eaching] A[ssistant], and people that aren’t on their phones are definitely getting more out of recitation,” Donovan said. “I think that if you’re paying for college, you should be responsible enough to stay off your phone.”

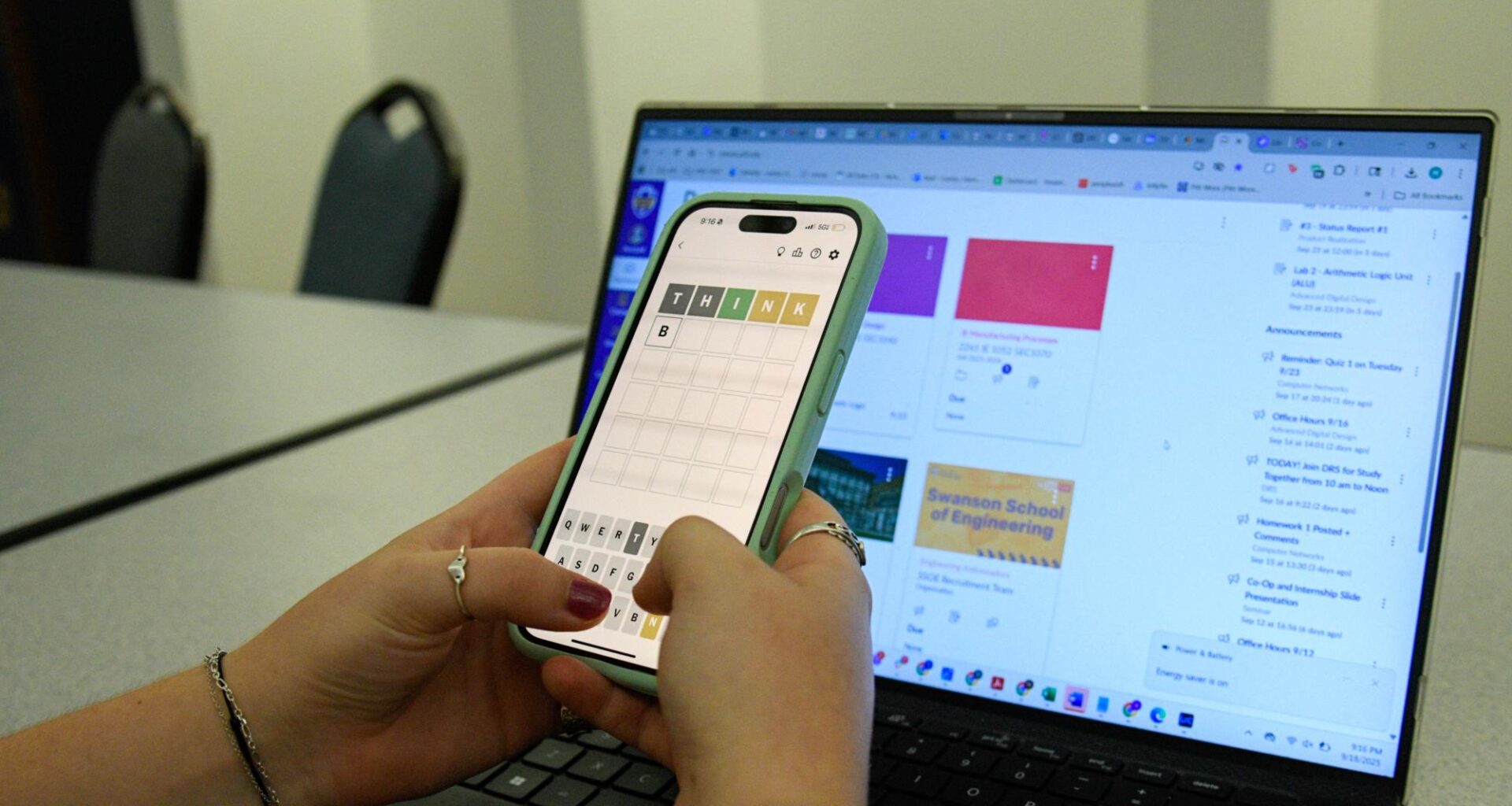

Riya Desai, a sophomore political science and music student, often becomes distracted in class doing homework for separate classes, scrolling online or playing The New York Times crossword puzzle. Despite distractions, Desai believes phone bans would be ineffective.

“It’s dumb because there are emergencies,” Desai said. “People wouldn’t listen to a phone ban in classrooms.”

Alexa Pierce, a second-year graduate student in the School of Public Health, said focused technology use in her classes is a classroom expectation, not a set rule.

Though she said phone bans in high school could be enforced, Pierce is reluctant about technology restrictions in higher education.

“In high school, it can be more contained,” Pierce said. “I feel like now in classes, I don’t see people scrolling on their phones with the professor talking. There are more discreet ways to [scroll] in the back or in the corner.”

For some professors, the line between freedom in the classroom and “banning” items is thin.

Amy Murray Twyning, Director of Undergraduate Studies in the English Literature department, does not believe in outright banning screens in the classroom. However, she expects her students to use physical books and printed articles instead of online resources during class.

“There’s nothing wrong with the technology,” Murray Twyning said. “It’s the habits of mind and concentration that I’m trying to encourage.”

Murray Twyning said she has not received any pushback from students for her screen policy against both laptops and phones. Instead, she said it’s an agreement between the students and professor, rather than a ban.

“I think banning makes it adversarial,” Murray Twyning said. “I’m not at odds with my students. I do believe that there is something really valuable [about paper]. And I will tell you, it’s less stressful to be just working with books in class — for everybody.”

According to Murray Twyning, her policy discouraging screens in the classroom is effective, and she is seeing the results of more professors moving towards real-world engagement in work.

“I have seen incredible work [this year] from students — really brilliant stuff that I haven’t seen in the past two or three years,” Murray Twyning said. “And I don’t think that’s because I’m banning screens, but because I’m making other things possible.”