SELKIRK — James Selkirk was an unlikely hero of America’s Revolutionary War.

The Scottish immigrant, who arrived in the colonies with next to nothing, chose to serve more than seven years in George Washington’s Continental Army. His personal writings helped historians understand the struggle of a common soldier.

He later settled on land in what is now the Albany County hamlet of Selkirk in the town of Bethlehem.

“The Selkirk family name is synonymous with the town of Bethlehem,” said William Ketzer, the town’s historian. “There’s a deep, deep legacy there. There’s a deep affinity for the land.”

But the municipality isn’t named for James Selkirk. That honor goes to Francis Selkirk, a farmer — and great-grandfather to 92-year-old Ron Selkirk.

Ron Selkirk, 92, stands in front of his home on a generations-old property. He and his wife, Judy, raised their four children in Coeymans before returning to the former farmland.

Five generations after James, Ron Selkirk now lives on the land James settled — where Ron was born, in Selkirk, on a fraction of the land his family originally held in a much different America.

“That family was profoundly affected by the sweep of history,” Ketzer said.

James Selkirk told the story of his life and service in a memoir, unpublished for 200 years and now being released in the forthcoming book, “James Selkirk’s Revolutionary War: The Memoir of a Continental Sergeant,” edited by Robb Haberman.

Ron Selkirk recounted his family’s tales to Ketzer in February 2025 for the Bethlehem Oral History Project, coloring between the black lines Ketzer drew via documents and photos on file. Ron spoke for about an hour from the home he shares with his wife Judy.

The house was built in 1988 after the last of their four children left the nest. A modern barn — more like a garage — sits across the driveway. The couple’s bedroom faces east so the sunrise wakes them. A sunroom was added a few years later.

Ron and Judy Selkirk live in their 38-year-old Maple Avenue home in Selkirk, pictured Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. Their property now is a fraction of the 600 acres the family used to own when the Selkirks were farmers.

“We didn’t have to buy land to build a house,” Ron said. “My wife’s here. So’s the farm.”

A generations-old grandfather clock booms at the top of the hour. Family portraits are hung nearly on top of one another — from cellphone era all the way back to dry plates. Relics from Ron’s days as a farmer are stored in the basement.

In the back of the house in a crowded guest bedroom is the retiree’s only physical connection to James Selkirk and the 18th century: a copy of his third-great-grandfather’s honorable discharge, signed by his commander-in-chief, George Washington.

During Ron Selkirk’s interview for the project, he rattled off his ancestor’s story with great accuracy, even though he said he “hardly ever” heard about the man in his youth.

“I wondered about it,” Selkirk said. “Selkirk from Selkirk? That can’t be.”

This panoramic view of Selkirk’s Poultry Farm on River Road in Selkirk was taken by Ron Selkirk in 1946 when he was 13.

Bethlehem Oral History Project

A teenaged James Selkirk landed in what is now Saratoga County’s Galway with the Henry family, who settled the area with other Scots in 1775 at the brink of the Revolutionary War.

“He lacks a support system. He doesn’t have family connections. He doesn’t have landed property. He doesn’t have great wealth,” Haberman said, painting a picture of the young James Selkirk. “Young men who lacked these economic opportunities and did not have prominent social status, they tended to join the Continental Army rather than the local militia.”

James Selkirk, who was sympathetic to the patriot effort, Haberman claims, served a longer, costlier term in the Second New York Regiment of Washington’s army.

During his time in the army, James kept a diary, long rumored in the family and recently rediscovered by former town historian Susan Leath. Soon to be published by Haberman, James wrote of a brutal experience.

Three generations of the family pose for a photo at Selkirk’s Poultry Farm in the late 1940s.

Bethlehem Oral History Project

“It’s important that with this personal account of James Selkirk that we hear the actual words and learn the specific firsthand experiences,” Haberman said. “We gain a better understanding of the suffering and sacrifices made.”

Among the high points: Selkirk fought in the Battle of Saratoga, the turning point of the Revolutionary War.

But there were of course many lows. He wasn’t paid during his service. He didn’t receive enough food, resorting to butcher scraps. He slept in tents and lacked proper clothing. Selkirk was injured and fell “severely sick” twice, Haberman said, including a spell that nearly “claimed his life.”

Though the patriots won the war, James Selkirk fell into a “depression” following his discharge, he wrote.

“While he’s proud to serve in the Continental Army and the fact that they have achieved this victory over the British military, he’s losing any sense of family and community that he has,” Haberman said.

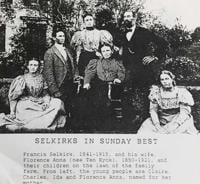

Ron’s paternal great-grandparents Francis Selkirk (1841-1915) and wife Florence Anna Ten Eyck (1850-1921), with children (L-R) Claire, Charles (Ron’s grandfather), Ida, and Florence Anna. Photo likely taken during very early 1900s on former family farm, now part of Selkirk railyards.

Bethlehem Oral History Project

Selkirk received land in Galway as pay and later sold the property to acquire more than 600 acres in what is now Bethlehem, where he became a farmer with his wife, Elizabeth Henry. The pair raised 10 children. He died in 1820.

As Ron tells it, the community of Selkirk was named in 1883, when the West Shore Railroad built a station in the hamlet. Common practice was to name a station after the town’s most prolific landowner, and in Bethlehem that was Jacob Soop. But “All off for Soop!” didn’t work, Ron said, and so James’ Selkirk’s grandson, Francis, also a farmer, was chosen as namesake.

Francis’ status would soon be lost. In 1917, the New York Central Railroad “took everything but the house,” Ron said, to build the Selkirk railyard for the Castleton Cut-Off freight line. The $25 million project replaced Albany West Yard and aimed to improve freight congestion throughout the state.

“In the name of progress people have to make a lot of sacrifices,” Ketzer said. “His family is really representative of that all the way through.”

The project prompted Ron’s grandfather, Charles Selkirk, to purchase a 100-acre property east of the railyard. There he opened a poultry farm with his son, Robert.

Ron Selkirk shows off a vintage egg carton from the family poultry farm.

Bethlehem Oral History Project

Ron was born in 1933, shortly after the construction of Route 9 through Selkirk. He grew up a hard worker, he said, barely graduating from high school.

“It was a good business,” he said. “I liked working on the farm. … My father liked me for that.”

As a young adult, Ron served in the Army during the Korean War. When he returned home he found the farm cut in half by the construction through their property of Interstate 87 and Exit 22.

The highway connects New York City to the Canadian border and has brought significant financial benefits to the state. Like James and Francis, Robert and Ron Selkirk didn’t have much say in the matter.

“Generally, people of means can avoid Selective Service. People of means can avoid having a [highway] run through their property,” Ketzer said. “A lot of people also don’t have it like that.”

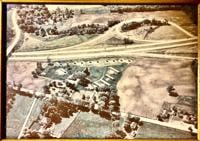

Aerial photograph of Selkirk’s Poultry Farm, showing extent of Thruway Exit 22 footprint on land previously in agricultural production. Late 1960s.

Bethlehem Oral History Project

When Robert retired in 1965, he left Ron with the egg business, including 4,000 hens — a small operation, according to Ron. New York once had a prominent poultry industry, Ketzer said, but by the time Selkirk took over it was foundering.

Policies from the Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon administrations subsidized produce, including eggs, making imported produce much cheaper than what Selkirk and New York egg farms could offer.

“In eight months I made only a couple of nickels,” Ron told the history project.

With no prospects in the chicken business, he sold more than half the property, bringing the once 600-acre family land total down to today’s 40 or so. He gave up the centuries-old family tradition and picked up jobs in gas and heating before going into freight hauling. Ron said he doesn’t know who lives in his original home today.

“And yet, somehow, he’s just the most mild-mannered, even-tempered fellow you’d ever want to meet,” Ketzer said. “Somehow they’re not bitter.”

Ron and Judy Selkirk live in their Maple Avenue home they designed in Selkirk, pictured Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. The property was built to its current state in 1988 when the family returned from a 20-year stay in Coeymans.

“I see in Ron the toughness, having gone through hardships,” Leath said. “And yet he’s a very kind man”

Ron and Judy Selkirk spent 20 or so years in Coeymans, Ron said, raising their four children before returning to the old poultry farm where they’ve lived since. Today their kids all live a stone’s throw from the land, with careers and families of their own, and still come home for holidays — Carrie down the road; Christopher in Richmondville; Jennifer in Albany; and in Ravena, James — named for the first Selkirk.

“I had heard how important he was in the Revolutionary War,” Ron said.

The hamlet of Selkirk sign is erected on top of I-87, pictured Friday, Jan. 9, 2026. The interstate was developed over the Selkirk family property in the late 1950s, while Ron Selkirk was serving in the Korean War.