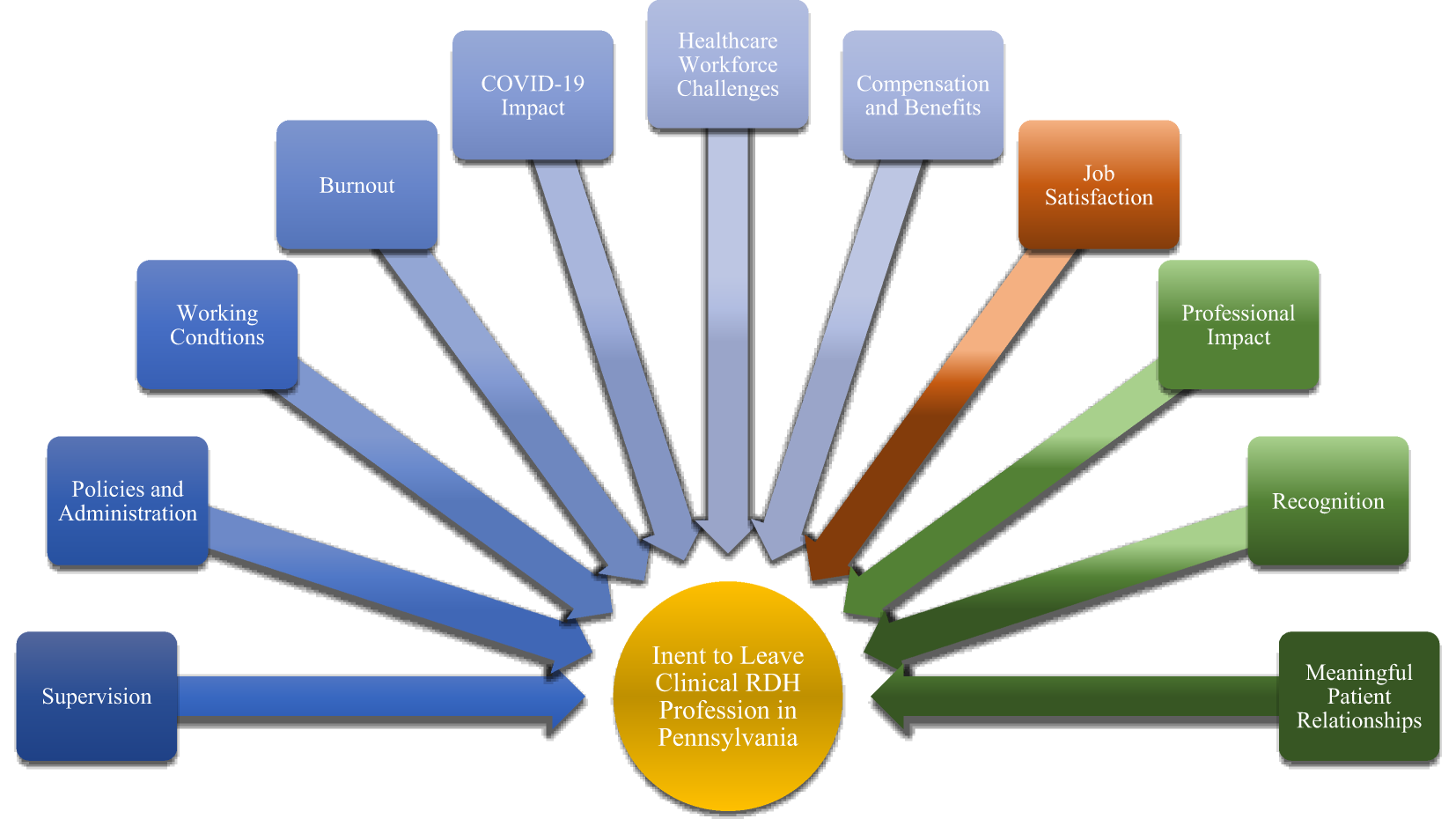

The distribution signifies an experienced workforce, with a substantial portion (52.7%) age 55 or older, indicating a risk of retirement-driven attrition for the profession. The lack of racial diversity reflects national workforce trends and may indicate limited representation within the dental hygiene profession. The data suggest that personal life stability, particularly in marriage, is a relevant factor in career satisfaction and retention. This high percentage of veteran professionals suggests that retirement-related workforce gaps could further intensify the dental hygiene shortage in Pennsylvania. The findings show that the large majority of RDHs work in private practices, but alternative employment settings are emerging, particularly within corporate and educational roles. Traditional career ladders are limited in private practices. While some practices may offer lead hygienist or managerial roles, and some hygienists become practice owners in partnerships with dentists, formal advancement pathways are uncommon.

Consistently with national trends [9], pay and benefits emerged as a major source of dissatisfaction, with more than 66% of respondents agreeing that raises were too infrequent. Career advancement was also a significant concern, reflected by a high mean score (5.01) for “There is really too little chance for promotion,” corroborating reports of stagnant growth in the field [6]. Limitations on promotional opportunities continue to undermine long-term engagement. Organizational policies, communication gaps, and bureaucratic barriers were frequent sources of dissatisfaction among survey respondents, and are consistent with broader professional patterns [12]. Respondents frequently expressed frustration with internal rules impeding effective work. These findings suggest that among respondents, salary is a concern, however, improved wages alone may not reduce turnover unless coupled with opportunities for career growth.

Conversely, coworker relationships were a key satisfaction factor. High scores for statements like “I like the people I work with” align with previous research showing collegiality buffers against dissatisfaction [21]. Supervisory support was also generally perceived positive, though varying by setting, consistently with findings by Al Zamel et al. [22], highlighting the impact of leadership on job satisfaction. Strengthening communication with supervisors could further enhance morale.

These results align with Herzberg’s two-factor theory [23], suggesting that while intrinsic motivators like pride in work are strong among surveyed RDHs, dissatisfaction with external factors such as pay, benefits, promotion, and policies remains a concern. This pattern of high intrinsic satisfaction coupled with low extrinsic satisfaction is characteristic of Herzberg’s framework. It typically predicts high job commitment, as employees derive fulfillment from the nature of their work, yet it also results in frequent dissatisfaction due to unmet expectations regarding external rewards. Addressing both dimensions may be critical to improving RDHs’ workforce satisfaction. However, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to determine causal relationships, and the findings should be interpreted within the context of the survey sample.

Pay and benefits. Survey results indicated significant dissatisfaction with pay among Pennsylvania RDHs, with 60.4% (n = 198) disagreeing that they were fairly paid. This aligns with Herzberg’s two-factor theory of motivation [23], in which classifies salary as an external, or “hygiene” factor that prevents dissatisfaction but does not inherently increase job fulfillment. While pay remains a concern, the findings suggest that improved wages alone may not reduce turnover unless coupled with meaningful career growth opportunities.

The mean score for the item “I feel I am being paid a fair amount for the work I do” was 4.06, with 39.6% (n = 130) agreeing slightly, moderately, or very much that they were fairly compensated. Perceptions of pay fairness vary among work settings, highlighting differences in pay and benefit satisfaction between private dental practices, public health facilities, DSOs, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), educational institutions, and government settings. By comparison, DentalPost’s reported in its annual salary survey that 29% of RDHs nationwide expressed dissatisfaction with their pay, indicating that Pennsylvania hygienists experienced greater dissatisfaction than the national average [24].

When asked about raises, participants showed higher dissatisfaction. The item “Raises are too few and far between” received a mean score of 4.47. A majority, 66.8% (n = 219) agreed that opportunities for raises were inadequate, highlighting this as a significant concern across various work settings.

Among respondents in this sample, a statistically significant but weak relationship was observed between the perception that “The benefits we receive are as good as most other organizations offer” and the primary work setting of the respondent (p =.0118, Cramér’s V = 0.187), indicating a moderate statistical significance with practical implications for organizational policy. These findings indicate notable differences in how benefits are perceived in various work environments. Respondents in FQHCs and educational institutions exhibited the highest levels of agreement, with 45.5% and 40.0%, respectively, strongly agreeing that the benefits they received were comparable to those offered by other organizations. This suggests that these settings are regarded as offering competitive or comprehensive benefits, likely due to the structured benefits packages commonly associated with government-supported and academic institutions.

Respondents from private dental practices reported higher dissatisfaction with benefits, with 27.1% strongly disagreeing and 15.9% moderately disagreeing that their benefits matched those of other organizations. This suggests that benefits in private settings are often viewed as inadequate in comparison to those of larger organizations or public institutions. DSO respondents displayed polarized views: 22.7% strongly disagreed, but 27.3% moderately agreed, suggesting variability in corporate benefits, likely due to organizational policies or geographic disparities. By contrast, government-employed RDHs reported the highest satisfaction, with 50.0% strongly agreeing that their benefits were competitive.

FQHCs and educational institutions also showed strong satisfaction, with 36.4% and 40.0% respectively strongly agreeing that their benefits were equitable. Private practices and DSOs, however, exhibited divided perceptions, reflecting inconsistency in benefits across corporate and private settings. Government respondents, though fewer, consistently reported higher satisfaction, likely due to standardized benefits structures. The “other” employment category showed mixed views, with notable disagreement and moderate agreement. A chi-squared test confirmed a statistically significant relationship between perceived benefits equity and primary work setting (p =.0118, Cramér’s V = 0.187).

Regarding raise frequency, DSOs expressed the highest dissatisfaction, with 63.6% strongly agreeing that their raises were too infrequent. Public health facilities also showed concern, with 66.6% of respondents agreeing either slightly or strongly. Private practices revealed mixed views: 39.6% strongly agreed, 16.9% moderately agreed, and 21.7% slightly agreed about raises being insufficient. FQHCs reflected moderate dissatisfaction, while educational and government settings displayed polarized perspectives. The “other” category also indicated diverse opinions regarding raise frequency.

Promotional opportunities. Promotional opportunities constituted a major area of dissatisfaction among respondents. The item “There is really too little chance for promotion on my job” received a mean score of 5.01, the highest among all items. A substantial 87.1% of respondents (n = 286) agreed slightly, moderately, or very much that promotional opportunities were too limited, while only 12.8% (n = 42) expressed disagreement. This reflects a widespread perception of poor advancement opportunities in the profession.

The analysis revealed a statistically significant relationship between the perception that “There is really too little chance for promotion on my job” and the primary work settings of dental hygienists, with a p-value of 0.0042 (very clearly significant) and a medium effect size of 0.195 (Cramér’s V). This indicates that perceptions of promotional opportunities vary meaningfully among work environments.

Respondents in FQHCs and DSOs expressed the highest levels of agreement with the above statement. In FQHCs, 72.7% of respondents agreed “very much,” and in DSOs, 54.5% agreed “very much.” These results highlight widespread dissatisfaction with promotional opportunities in these organizational settings, potentially due to more rigid structures or limited career advancement pathways.

Participants from private dental practices also showed strong agreement with the statement, with 52.7% agreeing “very much” and 22.2% agreeing “moderately,” indicating that lack of advancement is a significant concern in smaller practices. Similarly, respondents from public health facilities demonstrated substantial agreement, with 50.0% agreeing “very much” and 33.3% “moderately,” reflecting perceived limitations to growth opportunities in this setting.

In educational institutions, 40.0% of respondents agreed “very much,” but the responses were more evenly distributed across other levels of agreement and disagreement. This suggests a mix of experiences, potentially depending on the institution’s structure or the roles occupied by respondents. Those from government settings, on the other hand, exhibited greater variability, with 50.0% agreeing “moderately” but only 25.0% agreeing “very much,” reflecting a slightly more optimistic view of promotional opportunities than in other settings.

Supervision. Most participants reported positive perceptions of their supervisors’ competence. “My supervisor is quite competent in doing his/her job,” received a mean score of 4.42, with 76.8% (n = 252) agreeing and 23.2% (n = 76) disagreeing, suggesting room for improvement in supervisory relationships. “My supervisor shows too little interest in the feelings of subordinates” had a lower mean score of 3.04, suggesting some dissatisfaction with interpersonal aspects of supervision, though it was less pronounced than in areas like pay, benefits, or promotion.

Coworker relationships. The statement “I like the people I work with” received one of the highest mean scores (5.06), with 90.9% (n = 298) of respondents agreeing to some extent. This reflects strong positive coworker relationships among RDHs, a factor that can mitigate dissatisfaction in other workplace areas.

Private dental practices and FQHCs reported similarly high levels of camaraderie, with more than 40% of respondents in each setting agreeing “very much” that they liked their coworkers. Public health facilities and DSOs showed the highest levels of strong agreement (50.0%), although a small minority in DSOs did report disagreement, indicating some variability. In educational institutions, 40.0% agreed “moderately” and 33.3% “very much,” showing generally positive coworker relationships. Government settings showed more mixed experiences, with 50.0% agreeing “moderately” but 25.0% disagreeing slightly or strongly.

A chi-squared test revealed a statistically significant relationship between perceptions of workplace conflict (“There is too much bickering and fighting at work”) and primary work setting (p =.0193, Cramér’s V = 0.183). Respondents from private practices and FQHCs reported lower perceptions of conflict, with high rates of disagreement that bickering was a problem. By contrast, DSOs and government settings reported higher agreement that interpersonal conflict was present. Public health facilities and educational institutions showed more polarized distributions, with both agreement and disagreement about workplace conflict being common.

Organizational environment. Perceptions of the organizational environment were divided. For “Communications seem good within this organization,” the mean score was 3.45, with 46.3% (n = 152) agreeing and 53.7% (n = 176) disagreeing. Similarly, “Many of our rules and procedures make doing a good job difficult” received a mean score of 3.28, with 53.7% (n = 176) agreeing that bureaucratic barriers interfered with their work.

The analysis revealed a statistically significant relationship between the perception that “There are benefits we do not have which we should have” and the primary work setting of dental hygienists, with a p-value of 0.0089 (very clearly significant) and a medium effect size of 0.189 (Cramér’s V). Respondents in dental support organizations were most likely to “agree very much” with this statement (45.5%), suggesting that professionals in these settings perceived a strong need for additional benefits. Conversely, respondents in government settings showed mixed responses, with a significant proportion (75%) agreeing “slightly” with the statement, which may reflect less urgent dissatisfaction with benefits than in other groups. Those in FQHCs had higher rates of disagreement, with 27.3% saying they “disagree very much” with that statement, indicating that employees in those settings already had more comprehensive benefits packages or perceived fewer gaps in the available benefits.

Educational institutions displayed polarized trends, with notable proportions of respondents both agreeing “very much” (20%) and disagreeing “very much” (26.7%), reflecting a diversity of perspectives on the benefits in academic environments. Similarly, participants in private dental practices showed a balanced distribution across all levels of agreement, with 32.9% agreeing “very much” but a significant proportion also disagreeing to varying extents. Finally, the “other” category showed some dissatisfaction, with 22.7% agreeing “moderately” and 18.2% agreeing “very much,” suggesting a wide variety of experiences and perceptions among respondents in unconventional or unspecified work settings.

A statistically significant relationship exists between the perception that “My supervisor is quite competent in doing his/her job” and the primary work settings of dental hygienists, with a p-value of 0.0127 (very clearly significant) and a medium effect size of 0.186 (Cramér’s V). These findings suggest that perceptions of supervisory competence vary significantly among work settings. In private dental practices, the majority of respondents expressed positive perceptions of their supervisors, with 34.3% agreeing “moderately” and 30.9% agreeing “very much.” This indicates that supervisors in these settings are generally regarded as competent, probably due to closer and more consistent professional relationships in smaller, practice-based environments. Respondents in DSO settings also showed relatively high agreement, with 27.3% agreeing “slightly” and 22.7% “very much,” although this group also displayed notable disagreement, reflecting mixed perceptions in these organizational structures.

By contrast, respondents from federally qualified health centers and public health facilities displayed more polarized distributions. In FQHCs, 27.3% disagreed “moderately,” reflecting dissatisfaction with supervisory competence, while another 27.3% agreed “moderately,” showing a split in perceptions. Respondents from public health facilities showed similar divergence, with 33.3% disagreeing “slightly” and equal proportions agreeing “moderately” or “very much.” These trends suggest variability in supervisor quality in publicly funded or governmental health organizations.

In educational institutions, the responses skewed positively, with 26.7% agreeing “very much” with the above statement and no respondents expressing strong disagreement. This reflects a generally favorable perception of supervisor competence in academic environments, where leaders may prioritize mentorship and professional development. In government settings, on the other hand, 75% agreed “moderately,” suggesting a strong consensus that supervisors are moderately competent, though sample size limitations in this group should be considered.

Recognition and appreciation. Participants reported moderate dissatisfaction regarding recognition and appreciation. For “When I do a good job, I receive the recognition for it that I should receive,” the mean score was 3.75, with 52.7% (173) agreeing and 47.3% (n = 155) disagreeing. Similarly, “I do not feel that the work I do is appreciated” had a lower mean score of 3.17, with 47.6% (n = 156) agreeing and 52.4% (n = 172) disagreeing.

Job enjoyment and pride. Despite concerns about pay, benefits, and promotion, respondents reported high levels of enjoyment and pride in their work. The statement “I like doing the things I do at work” received a mean score of 4.98, with 89.6% (n = 294) expressing agreement. The highest mean score across all items was for “I feel a sense of pride in doing my job,” which scored 5.31, with 94.2% (n = 309) indicating agreement.

The findings contribute to the body of knowledge on dental hygiene by providing a state-specific, validated analysis of job satisfaction using the JSS instrument. This study adds depth to discussions of workforce problems in dental hygiene by linking dissatisfaction with modifiable organizational and regulatory factors. This research also lays a foundation for longitudinal studies to track the evolving nature of satisfaction among RDHs and examine how systemic reforms influence professional engagement over time.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be considered in the interpretation of these findings. Although the JSS is a validated instrument, it was originally developed for general human service settings and may not fully capture dental hygiene-specific satisfaction factors. Recruitment bias may exist, as the participants were drawn primarily from professional conferences, potentially excluding RDHs who are not engaged in professional networks. This could have skewed the results toward more connected individuals, underrepresenting rural or underserved populations. The use of self-reported data introduces the potential for response bias, including social desirability and recall bias. Additionally, the high proportion of respondents aged 55 and older may skew results toward the perspectives of late-career RDHs. Sampling imbalances may also have affected the findings. Private practice and DSO settings may be overrepresented, and RDHs in rural, public health, education, and government roles may be underrepresented, limiting any insights into the full workforce. Future studies should incorporate randomized or stratified sampling to ensure broader representation.

The focus on Pennsylvania further limits generalizability, as the findings reflect the state’s unique regulatory environment, including its exclusion from the interstate licensure compact. The results may not directly apply to RDHs in states with different policies. In addition, only participants’ primary jobs were examined, which means any influence of secondary employment was overlooked. As a cross-sectional study, this research is limited to capturing a single time point and cannot establish causality. Longitudinal research could capture evolving satisfaction trends. This study did not employ multivariate statistical techniques such as regression modeling to assess the relative influence of intrinsic versus extrinsic factors on turnover intent. Future research should address this to capture the complexity of these relationships. Despite these limitations, this study offers valuable insights into the factors influencing RDHs’ job satisfaction in Pennsylvania and highlights areas in which future research can improve understanding and support of the workforce.