To kick-start Hispanic Heritage Month, students at Brashear High School festooned the building’s south wing corridors with bright murals, forming a tapestry of color that reflects the school’s diversity.

A pillar is painted with flags from countries around the world alongside a painting of a man holding a letter that says, “We the people of all nations.”

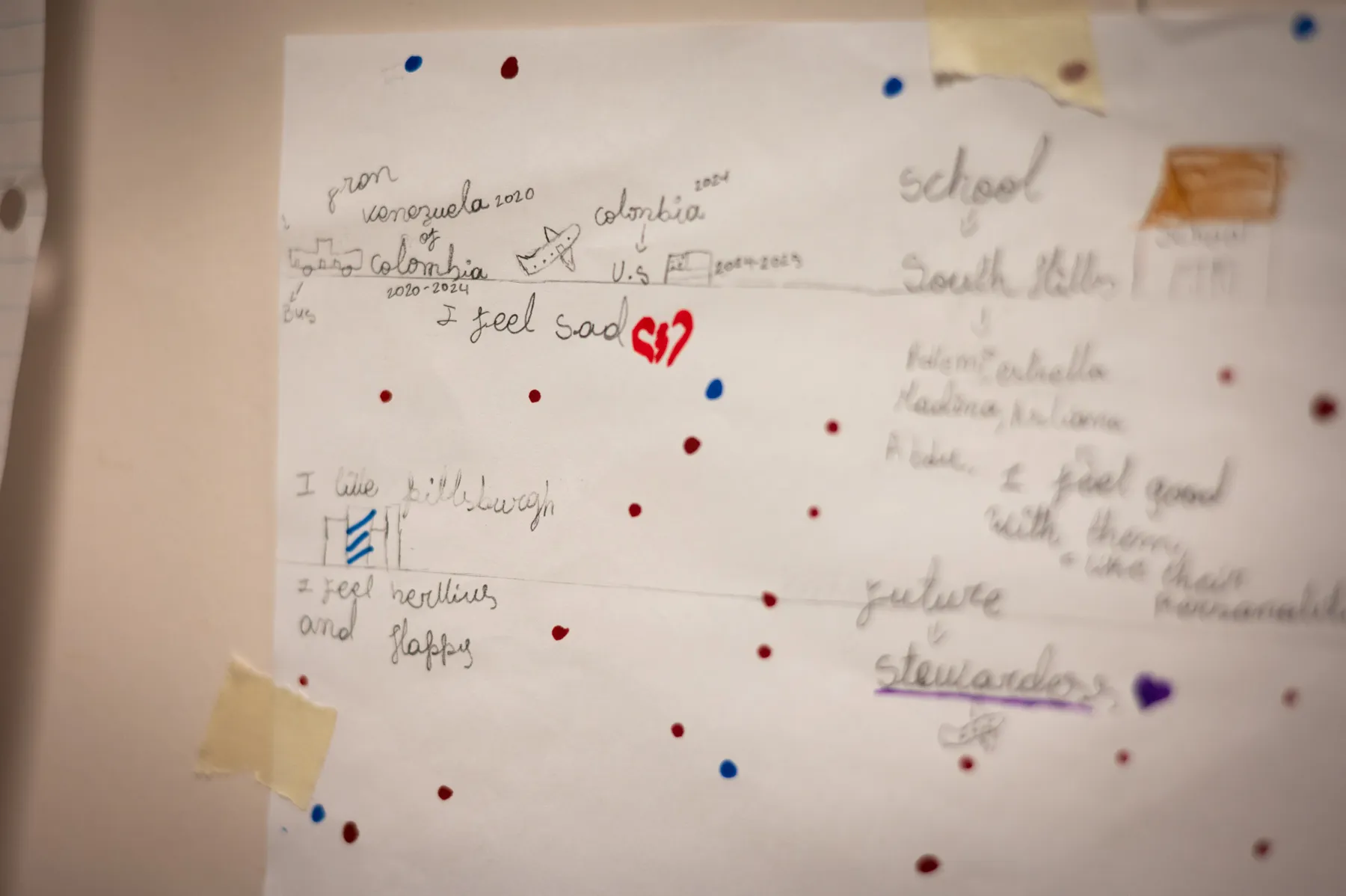

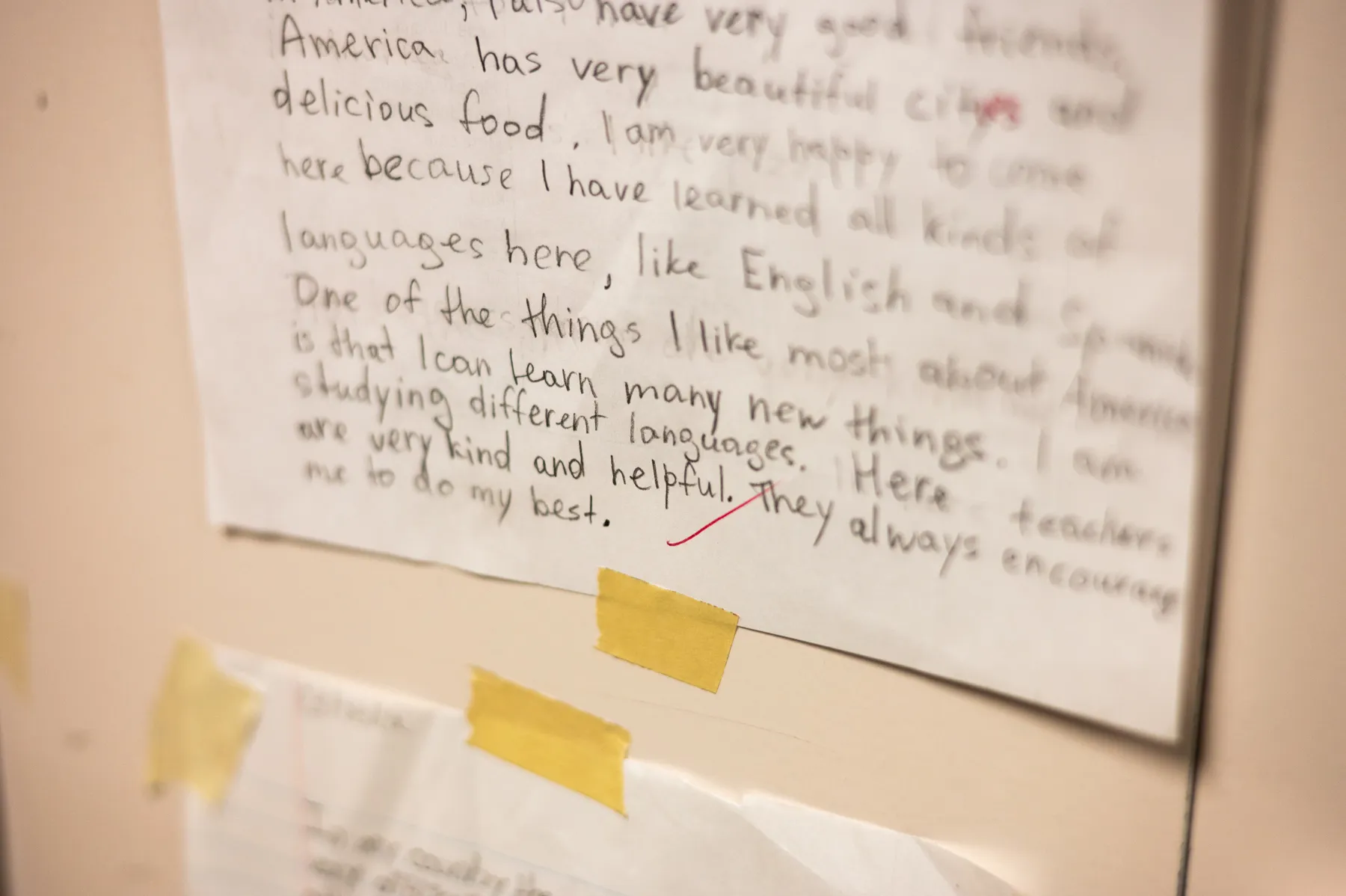

Flags of various countries are also hung throughout the hallway with information about languages, currency and landmarks. Another wall highlights stories of students who immigrated to Pittsburgh from Venezuela, Uzbekistan, Colombia, Honduras and other countries, charting their journeys to the U.S.

This part of the building belongs to the school’s English Language Development (ELD) department, where immigrant or refugee English learners have their classes. With around 50 languages spoken among the students, Brashear is one of the most culturally diverse schools in Pittsburgh Public Schools (PPS).

Around 40% of Brashear’s student population are English Language Learners (ELLs), a fast-growing demographic across PPS. For the school’s staff, Brashear’s linguistic, cultural and racial diversity is a point of pride.

Brenda Cassler, center, a therapeutic emotional support teacher at Brashear High School, laughs with students ahead of a powderpuff football fundraising game on Oct. 9. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Brenda Cassler, center, a therapeutic emotional support teacher at Brashear High School, laughs with students ahead of a powderpuff football fundraising game on Oct. 9. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

But as the ELL student population has exploded, the school has struggled with unstable leadership and inadequate ELD staffing, and has seen high rates of suspensions, truancy and chronic absenteeism.

Over the years, community organizations have become central allies in tackling these challenges as the school navigates a growing immigrant student population.

Spanish speakers make up the majority of English learners at Brashear. Organizations Casa San José and Latino Community Center (LCC) have partnered with the school to provide a welcoming environment to those students by helping families to enroll in appropriate grades, provide translation services and feel a sense of community.

Piero Medina, youth program coordinator at Casa San José, visits the school every day to provide mentorship and assistance to students.

English Language Learners at Brashear work in the digital media room at Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, Oct. 10, through Jóvenes con Próposito (Youth with Purpose), an after school program organized by Casa San José that engages ELL students with the arts. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

English Language Learners at Brashear work in the digital media room at Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, Oct. 10, through Jóvenes con Próposito (Youth with Purpose), an after school program organized by Casa San José that engages ELL students with the arts. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

On Tuesdays, the organization runs an in-school program called Casita, which provides cultural engagement and skills development activities. They also have programs with the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild Youth in which students participate in photography, clay work and 3-D printing.

LCC has helped English language learners and families navigate the public school system through their Education Support program. Over the years, they have assisted families with enrollment, scholarships, truancy and overall communication with schools.

This year, LCC Founder Rosamaria Cristello said, more families are struggling with regular attendance because of fears of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers present in their neighborhoods. In response, the organization helped bridge communication gaps by explaining the importance of attendance to families, while telling schools why a student might be absent.

“It’s not unique to Brashear, I think a lot of the schools are struggling with that piece,” Cristello said.

Work from English Language Learners hangs in the hallways of Brashear’s English Language Development section on Oct. 9. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Work from English Language Learners hangs in the hallways of Brashear’s English Language Development section on Oct. 9. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Juli Kuhns, a counselor at Brashear, said while organizations like Casa San José and LCC make a huge difference for the school’s Spanish-speaking students, she would love to see more community support for students who speak other languages.

ARYSE, a nonprofit that serves immigrant and refugee youth in the region, has been advocating for improved staffing and working conditions for the district’s ELD teachers.

Jenna Baron, executive director of ARYSE, said concerns among ELD teachers have grown since the district announced its Future-ready Facilities Plan.

Under that sweeping plan, which the board is expected to vote on later this year, the district would increase the number of ELD centers to improve student support, reduce travel time for teachers and students and strengthen ties with families.

ARYSE wants teachers, families and other key stakeholders to be directly involved in shaping how the new ELD centers could be reimagined with improved staffing, training and resources. They have also urged the district to provide professional development training for itinerant ELD teachers who might feel isolated and in need of support.

“Through that shared advocacy work, I’ve also come to see that the conditions for the teachers themselves are unacceptable, that they don’t feel listened to, they don’t feel like they have the resources to support their students,” Baron said, adding that many teachers she spoke to were considering leaving if their perspectives keep getting dismissed.

Students outpace hiring

There were around 271 students receiving ELD services at Brashear during 2024-25, making the total ELL population around one-third of the student population. In just one year, staff said, the total number of English learners has risen to 40%, and the school is still enrolling new students.

Esther Omoi, a native Swahili speaker, talks about her experience as an English Language Learner at Brashear High School, Oct. 9. Omoi is working on the murals in Brashear’s English Language Development wing. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Esther Omoi, a native Swahili speaker, talks about her experience as an English Language Learner at Brashear High School, Oct. 9. Omoi is working on the murals in Brashear’s English Language Development wing. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

For the ELD department, the rapid increase brings a mix of joy and concern.

Eduardo Fajardo, a teacher at Brashear, said the sharp jump in ELL numbers has not prompted any new ELD hires. And while the school has many bilingual teachers, many are not native speakers and often lack cultural understanding to communicate with students effectively, they added.

Jonathan Covel, ELD director at PPS, said Brashear has not hired more teachers because the school offers enough classes to meet the district’s recommendations for English learners based on their proficiency levels in English.

This year, Brashear has five ELD teachers teaching at different proficiency levels, five content area teachers who provide support in subjects like math, science and social studies and four multilingual classroom assistants.

Micheline Al Choufete, an ELD educational assistant, supports Arabic-speaking students in a math class for English Language Learners, Oct. 9 at Brashear. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Micheline Al Choufete, an ELD educational assistant, supports Arabic-speaking students in a math class for English Language Learners, Oct. 9 at Brashear. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

He said the district offers an internal ELD certification program to interested teachers for free or reduced cost and encourages teachers in any subject to get certified to equip them for schools with more English learners. The district prioritizes bilingual teacher applicants, though it is not required, but this hasn’t increased the share of native language-speaking teachers, he said.

Covel said factors like the reduction in people becoming teachers and immigration issues or state certification requirements for international teachers have resulted in fewer ELD applicants in the last few years.

PPS conducts three professional development sessions with ELD teachers throughout the school year, plus sessions with temporary teachers on every half-day.

Principal Christina Loeffert said Brashear has hired many teachers outside the ELD department who are from different countries and can fill in the cultural gaps for students.

She said, “the only barrier we have from getting other native speakers” is that multilingual teachers already in the building enjoy working with ELL students and want to keep doing it themselves.

Principal Christina Loeffert sits for a portrait in her office at Brashear High School on Oct. 9. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Principal Christina Loeffert sits for a portrait in her office at Brashear High School on Oct. 9. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Finding stability

For a few years, Brashear struggled to maintain stable leadership, which some education advocates say can exacerbate issues of violence and absenteeism.

Between 2020 and 2024, Brashear cycled through four principals, according to the 2024 A+ Schools annual report. The last principal was placed on administrative leave following a violent altercation between two students.

James Fogarty, executive director of A+ Schools, said schools with a high principal turnover often have difficulty implementing school-wide initiatives and delivering improvements. Some new leaders might not take input from teachers about best practices, leaving them feeling isolated.

“Really well-intentioned folks on the teaching side are just going to… often close their doors and say, ‘I’m going to focus in on what I can control, which is my classroom, because I can’t control this constant change in systems and operations at the school level that are being shifted every time we have a new leader,’” Fogarty said.

He said the district needs to prioritize supporting school leaders, and develop site-based plans for each school and go beyond state and federal educational standards.

Rising ELL suspensions

Since Loeffert took the reins three years ago, she said, consistency is critical. She came to Brashear from the adjacent South Hills Middle School building in 2022 and got to work adjusting school practices based on student needs.

Despite efforts, suspension rates have slightly increased. Nearly one quarter of students were suspended in the 2024-25 school year, as suspension rates for English learners jumped from 6% to 19%.

“When English learners’ needs go unmet, it fuels disengagement, it fuels resistance, it fuels disciplinary issues that impact entire schools,” Baron said. “And you know we’re talking about Brashear, and I think it especially affects those schools that are serving communities where there’s concentrated poverty.”

Students board school buses outside Brashear on Sept. 11, 2024. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

Students board school buses outside Brashear on Sept. 11, 2024. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

She added that sometimes, these challenges are intensified because of structural gaps, such as a lack of translators or interpreters, leaving the school to pull bilingual teachers or paraprofessionals from classrooms to fill those gaps.

“Where there are schools where English learners are the minority, there’s a greater risk of bullying, discrimination, de-prioritization of resources that could be really essential to them accessing their education,” Baron said. “So it … feels a bit riskier to me when those resources aren’t centralized, that students would experience more isolation.”

Loeffert and the school staff have taken a proactive approach by encouraging reintegration meetings, a restorative practice in which school staff meet with parents and guardians to discuss behavior issues and help students return to school after a suspension. They try to intervene before issues lead to violence.

“Our large fights have gone down dramatically, and now we’re just dealing with some one-on-one things that usually stem from the community,” she said.

Brashear is one of the six PPS schools that participates in the Safe Passage program in partnership with Operation Better Block, the City of Pittsburgh and the Buhl Foundation. Loeffert has appointed two community members, one of whom is Medina of Casa San José, to work with youth safety ambassadors and serve as violence interrupters. The ambassadors work to identify at-risk youth and help maintain peace in buildings.

“We have kids from all over that come to Brashear,” Medina said. “So I think it’s just a matter of connecting everybody, so that everybody feels welcome, and we try to reduce any kind of negative situations.”

Work from English Language Learners hangs in the hallways of Brashear’s English Language Development section Oct. 9. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Work from English Language Learners hangs in the hallways of Brashear’s English Language Development section Oct. 9. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Cristello said that schools like Brashear could validate students’ fears by providing them a safe space to talk about their experiences and trying to communicate with families. Other than providing interpretation services, schools must hire bilingual staff or work with parent liaisons to help immigrant families.

“It’s very hard, and sometimes nuances can be missed, versus if you have someone who speaks your language, it just removes all those barriers, and you can have a very honest conversation and a more meaningful conversation,” she said.

Fogarty said many of Brashear’s challenges around safety and stability are compounded by other factors.

“Not only do you have poverty, you have a mix of kids who are immigrant and refugee, students who are coming from all over the world to the school, [and] a native population that is currently being told by our president that immigrants and refugees are not to be welcomed,” he said.

Points of pride

Despite these challenges, students and teachers at Brashear say they find reasons for hope.

Devine Browne teaches Russian and French at Brashear. Oftentimes, he said, he uses his language skills to improve understanding between community members who speak Russian or French and other district staff and counselors.

He said other teachers in the building who speak languages like Spanish, Swahili, Nepali or Arabic take on the roles of interpreters to make families and students feel more welcomed at Brashear.

From left, students Abdullokh Abdugofurov, whose native language is Uzbek, Arslan Rozmukhamedov, a native Russian speaker, and Esther Omoi, who grew up speaking Swahili, talk about their experience as English Language Learners at Brashear High School on Oct. 9, in Beechview. The three help other ELL students arriving at the school to adjust. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

From left, students Abdullokh Abdugofurov, whose native language is Uzbek, Arslan Rozmukhamedov, a native Russian speaker, and Esther Omoi, who grew up speaking Swahili, talk about their experience as English Language Learners at Brashear High School on Oct. 9, in Beechview. The three help other ELL students arriving at the school to adjust. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Abdullokh Abdugofurov, a tenth-grader at Brashear, came from Uzbekistan to the U.S. in 2023, not knowing any English. Browne, speaking to Abdugofov in Russian, helped him fill out documents and get enrolled in South Hills. A year later, he came to Brashear and loves being part of the ELD classes. He said his English has improved vastly because of support from the teachers at both schools.

“Everything is perfect in the school. I like everything from the school,” he said. “Maybe people talk about our school bad, but I don’t know. I never seen bad things in our school.”

The school has adopted an informal peer mentor program to help newcomer ELD students find their way. Once older ELL students achieve a certain proficiency in English, they can become student ambassadors and translate for newcomers who speak their native language.

Teachers and staff members like Browne think Brashear’s diversity is what defines the school.

“The diversity in this building — the linguistic, cultural, religious, ethnic diversity in this building — is really a point of pride at Brashear. It’s one of the best reasons to be here as a staff person,” Browne said.

Lajja Mistry is the K-12 education reporter at Pittsburgh’s Public Source. She can be reached at lajja@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Tory Basile and Jamie Wiggan.

Your gift will keep stories like this coming.

Have you learned something new today? Consider supporting our work with a donation.

We take pride in serving our community by delivering accurate, timely, and impactful journalism without paywalls, but with rising costs for the resources needed to produce our top-quality journalism, every reader contribution matters. It takes a lot of resources to produce this work, from compensating our staff, to the technology that brings it to you, to fact-checking every line, and much more.

Your donation to our nonprofit newsroom helps ensure that everyone in Allegheny County can stay informed about the decisions and events that impact their lives. Thank you for your support!

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.