An installation view of “Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection” at the Kimbell Art Museum. Photo: Daniel Orr

An installation view of “Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection” at the Kimbell Art Museum. Photo: Daniel Orr

When he arrived in Rome in 1786, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe found himself moved to the core. Rome was far removed from his day-to-day political worries in Weimar, Germany. It served as a Mediterranean vacation that Goethe didn’t realize he needed, and put the poet-philosopher in touch with antiquity. Having received an education in Greek and Latin literature in the university towns of Germany, Goethe (1749-1832) mostly thought of the ancient world on the page, in the abstract, or saw it through the prints and paintings of Rome that dotted his childhood home. Going to Rome in his middle age changed all that. His connection to the ancient monuments like the Colosseum, the Forum, and the Pantheon was immediate: Goethe was occupying the same spaces that the ancient Romans had, walking in the ancients’ steps. Beyond the monumental scale, 18th century Rome was a city of statues and fragments, friezes and pediments, tomb markers, and fountains. While ancient masterpieces clogged the halls of the Vatican, more intimate markers of antiquity pervaded the city. The Rome Goethe first encountered in the 1780s was one of palaces and gardens, where the ruins of the Forum still occasionally doubled as public parks and even pasturage. Long before the advent of modern museums, the boundary between the city and the ancient world was permeable: turning a corner on one of Rome’s seven hills, Goethe could see a repurposed statue base or even a bust in a courtyard, constant testaments to how the ancient Romans saw themselves and the human condition. “In Rome,” Goethe wrote years later, “besides the population, there was also a population of statues.”

Goethe came to Rome a year too late to meet the patriarch of the banking dynasty that would assemble one of the most significant populations of ancient statues in the modern era. Born in Southern France, Marino Tourlonias brought his family and business savvy to Rome in the mid-18th century. When he died in 1785, the year before Goethe’s life-changing brush with the city, Marino left behind a dynasty with an Italianized name (Torlonia), business with the Vatican, and talent aplenty that could fund good taste. Under the next two generations of art-loving and successful scions (the Torlonia family did Napoleon’s banking), the Torlonia family bought private collections of ancient marble statues that had been prized possessions of (modern) Roman families in the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1876, the Museo Torlonia opened, making public the populations of statues that the family patriarchs had accumulated since Goethe’s lifetime as well as the statues excavated from Torlonia estates by archaeologists financed by the deep Torlonia pockets. Although the Museo Torlonia closed to the public during World War II, it has remained a collection of collections without parallel in modern Italy: keeping intact (and unusually well-documented) collections that had built up in the hands of antiquities-loving families since the Renaissance. The Museo Torlonia offers a rare window not just into the ancient world but also into the collecting sensibilities that characterized the pre-museum world. Where present-day Rome’s major collections of antiquities — the Vatican, the Capitoline Museum — are institutions with seemingly endless lines and non-existent air-conditioning, the Museo Torlonia remains a family affair, a remnant of the pre-institutional days of collecting.

In a first in its long history, the Museo Torlonia, in partnership with the Art Institute of Chicago, is taking a portion of its collection on a North American tour. The show, Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection debuted in Chicago and will travel to Montreal in 2026, is now on view at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth. With the Kimbell, the rare institution that is still guided by its founding family, the Torlonia marbles may have met their match. On display in the Piano Pavilion, the pieces from the Museo Torlonia benefit from Renzo Piano’s light-filled and orthogonal building as well as from the courtyard-like conditions the Kimbell’s exhibition designers have fostered.

Left: “Statue of Leda and the Swan,” late second century CE. Right: “Statue of Leda and the Swan,” first half of the second century CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

Left: “Statue of Leda and the Swan,” late second century CE. Right: “Statue of Leda and the Swan,” first half of the second century CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

It’s difficult to pin the show down to a single theme. The title Myth and Marble is a little misleading. There’s not much in the way myth: a statue of Odysseus beneath the ram (the way he escapes the clutches of the Cyclops in the Odyssey), two near-identical statues of Leda and the Swan, Cupid and Psyche in a youthful embrace, and sarcophagi showing the twelve labors of Hercules put myths on display, while a bevy of statues of gods dot the show.

As for the “Marble” in the title, all but one piece, a bronze statue that was excavated from the Torlonia estates in the 19th century and restored, come from the endlessly fascinating stone, though not all of that stone comes from ancient Rome itself — far from it. The polish and completeness that most of the pieces in Myth and Marble enjoy is no happy accident of time. Before the 19th century, collectors liked their ancient sculptures buffed up and appearing as they might have looked in antiquity. Although the Torlonia family amassed their population of statues contemporary with the birth of modern archaeology and the modern museum, the family made no effort to topple the preceding aesthetic of imitating the ancients. Authenticity and the beauty of the fragment, by contrast, are values that developed in Romanticism’s wake; they were not the founding values of the Museo Torlonia. Indeed, in the Renaissance, a fragmentary marble sculpture offered the up-and-coming sculptor a chance to imitate the masters; for the Renaissance, imitation was the foundation of creativity.

“Statue of a Resting Goat,” late first century CE. Note: The head of the sculpture has been attributed to Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Photo: Daniel Orr

“Statue of a Resting Goat,” late first century CE. Note: The head of the sculpture has been attributed to Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Photo: Daniel Orr

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), en route to sculpting such masterworks as Saint Teresa in Ecstasy, would practice on a headless Statue of a Resting Goat, complementing the detailed carving of the goat’s curly body with an exquisitely detailed face. Considerations for authenticity did not hinder Bernini or the Torlonia collections. And for that matter, authenticity did not have much appeal for the ancient world, either. Through the exhibition’s insightful signage, the curators show which portion of a statue or frieze that appears complete, was in fact restored or altered in the ancient or early modern world. By my count, well over three quarters of the pieces displayed were modified.

“The Old Man of Otricoli,” mid-first century BCE, and other pieces on view in “Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection” at the Kimbell Art Museum. Photo: Daniel Orr

“The Old Man of Otricoli,” mid-first century BCE, and other pieces on view in “Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection” at the Kimbell Art Museum. Photo: Daniel Orr

The focus that Myth and Marble places on ancient and early modern creative restorations comes as part of an ongoing trend that has tried to explain how our viewing of the ancient world is all too often transmitted through the preference and aesthetics of the more recent past. Recent shows on color in the ancient world, such as the Metropolitan Museum’s Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color, have helped to point out how the remains of pigmentation on sculpture, stonework, and even bronze show that polychromy pervaded ancient art, and that the ancient world was not as obsessed with unvarnished marble as were the taste-makers in the 18th century. Similarly, art historians continue to call into question an old verity that all Roman-period marble statues are just copies (read: inferior) of more ancient Greek bronzes (read: superior): it might be that the supposedly derivative Roman stone-carvers took more creative liberties than previous generations of art historians supposed. In a similar vein, the curators of Myth and Marble point out that some of the sculptures we see as authentically representing antiquity, such as what is probably the most well-known piece in the show, the so-called Old Man of Otricoli, is in actuality a product of modifications in the ancient world and the Renaissance.

Bronze statue, possibly of Germanicus, 15 BCE – 19 CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

Bronze statue, possibly of Germanicus, 15 BCE – 19 CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

Interestingly, the show’s organizers do not raise the question, “Why marble in the first place?” Practical, aesthetic, and symbolic explanations for the ubiquity of the gleaming stone abound. The Romans, to be sure, loved bronze statues — but so did anyone sacking Rome or anyone in need of copper and tin. Bronze statues were military arsenals in the waiting: a bronze statue contained countless spear and sword points as well as a small hoard of copper coins. And besides this, bronze statues caused a religious obstacle after Rome became Christian in the fourth century CE: bronze statues of Roman gods presented an eye-sore that (thankfully, from the Christians’ perspective) could be smelted down. The only reason the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius survived in Rome from the second century CE to the present day (it’s now in Rome’s Capitoline Museum) was that Romans started to think that it was a statue of Constantine (reigned 306-337 CE), Rome’s first Christian emperor rather than the philosopher Marcus Aurelius.

But marble also had an intrinsic appeal for the Romans. It is plentiful in the Mediterranean, so much so that Romans (and modern art historians) can recognize varieties of marble based on provenance. While the marble from the Greek island of Paros and Mount Pentelikos, northeast of Athens, look equally creamy and gleaming to my untutored eyes, aficionados and experts could (and still can) tell apart two of the most popular marbles in antiquity. Closer to Rome, the Northern Italian quarries in Carrara produced another shimmery marble that was renowned for being easy to carve — it was from Carrara that Michelangelo got the rock to sculpt his David and his most famous pieces. The most exotic marble in the Roman empire came from Egypt, where geological forces which existed nowhere else in the Mediterranean world produced red, gray, green, and purple marbles. The show’s gray marble statue of the Nile River, the Torlonia Nile, did double duty in antiquity as a fountain and now sprawls in the middle of the main gallery at the Kimbell. For an ancient Roman, Torlonia Nile would have stood out for its rich gray that Romans associated with the fabled Egyptian quarries.

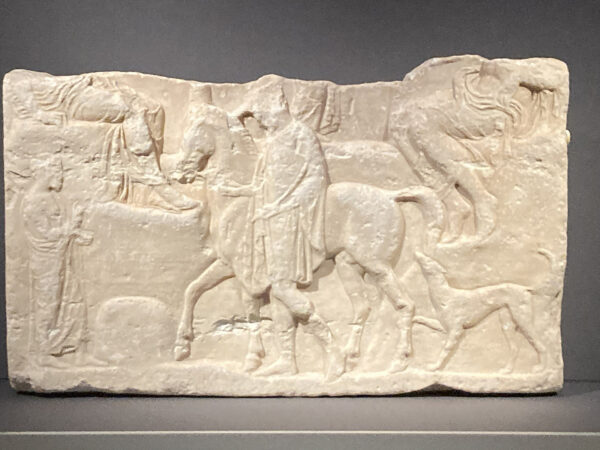

“Relief of Mithraic Sacrifice,” second century CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

“Relief of Mithraic Sacrifice,” second century CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

Aside from being plentiful in the Roman Empire, carving marble involved fewer steps than casting bronze, fewer tools, fewer workers (many of whom were enslaved), and was easy to sculpt. The carving techniques had a long lineage. Ancient Egyptians, Assyrians, and Hittites developed sophisticated sculpting and carving technologies for stone that was far harder than marble. The Greeks benefitted from their neighbors’ technical prowess and from the abundance of a medium that was easier to carve. Roman sculptors learned all of the Greeks’ secrets and made their own innovations, too. Greek and Roman sculptors could achieve a level of detail that continues to astound — like the swoop of the cape and locks of hair of a second-century relief that depicts the sacrifice of a bull for the mystery religion of Mithras.

And marble glistened. Marmor, the Latin word for marble, derives from the ancient Greek marmaros, which means any generic crystalline rock that glitters in the sun. Marble and granite alike fell into the category of marmaros. When ancient Greeks saw marble, they saw the complex crystalline structure that is easy to miss in a contemporary museum gallery, but practically blinds someone under the bright Mediterranean sun. Under such conditions, a marble statue could be polished to glitter like bronze from a distance. This aesthetic quality of the stone lends a symbolic value. When the heroes in the Iliad and Odyssey move across the battlefield, they are marmaroi, their bronze armor and sweat causing them to glitter. Greek and Roman sculptors would later make marble a medium for that heroic glisten.

In the subdued lighting of the Piano Pavilion, the sculptures of Myth and Marble look much the same way as they do in museums around the world — impressive, but lifeless. In opening up the space of the main exhibiting area, the Kimbell gives the impression of entering a palazzo courtyard. The open layout of the show makes getting around it easy, and easy to compare like and unlike pieces. At the wall opposite the entrance, a small forest of second century CE imperial busts invite the viewer to see how the emperor Hadrian (reigned 117-138 CE) popularized the beard for Roman emperors yet how his successors did not quite follow suit, with Antoninus Pius (reigned 138-161 CE) trimming his down to little more than an overgrown soldierly stubble, and Marcus Aurelius (reigned 161-180 CE) looking downright mangy compared to Hadrian’s voluptuous curls and Antoninus’ trim.

“Statue of Emperor on Throne with the Portrait of Augustus.” Note: Augustus’ portrait was placed on the body long before it entered the Torlonia collections. Photo: Daniel Orr

“Statue of Emperor on Throne with the Portrait of Augustus.” Note: Augustus’ portrait was placed on the body long before it entered the Torlonia collections. Photo: Daniel Orr

But when it comes to representations of Roman emperors, a beard is never just a beard; even the sculpting of an imperial family member’s hairstyle comprised part of the visual language of power, what Paul Zanker, who wrote the authoritative study on the art of the early Roman empire, called “the power of images.” Myth and Marble makes it possible to see key developments in the presentation of divine and human power. Roman emperors straddled that boundary between human and divine. No piece in the exhibition makes this point as well as the Statue of Emperor on Throne with the Portrait of Augustus. As the name suggests, the body of the statue and its head do not actually go together. The creative restorer found a head of Rome’s first emperor (reigned 27 BCE -14 CE) and stuck it on a body that looks more divine than human, holding a symbolic orb (from the Latin, orbis, meaning world, so this god-emperor has the whole world in his hand). Augustus, who was unique among the pantheon of Roman emperors for retaining an active cult presence long after his death, was an obvious candidate for topping this statue. He could very well be the most visually represented person from the ancient world: on statues, busts, jewelry, and coins across the Roman Empire. While there were some slight variations across time and space, his face would have been recognizable the world over. His beardless, ever youthful face could hardly be more different from the row of bearded emperors behind him in the Piano Pavilion, a clear reminder that the historical Augustus strove to present himself less as a Greek-looking (i.e. bearded) monarch than as a restorer of the Roman and republican restraint that is artistically associated with the The Old Man of Otricoli who greets the visitor just to the left of the show’s entrance.

“The Old Man of Otricoli,” mid-first century BCE. Photo: Daniel Orr

“The Old Man of Otricoli,” mid-first century BCE. Photo: Daniel Orr

With the beardless Augustus and The Old Man of Otricoli on one side of the spectrum, and the bearded emperors who followed Hadrian on the other, it is possible to trace the changes in the visual language of power that was bound up with the Roman emperors.

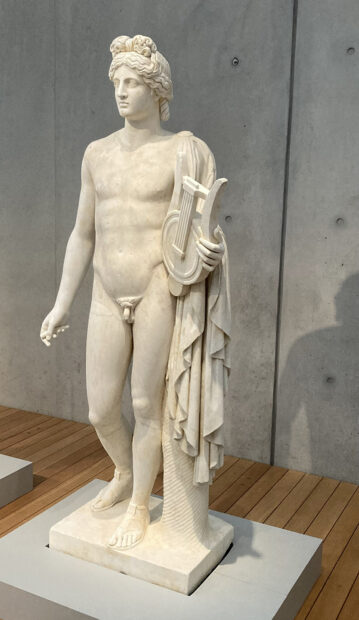

Likewise, the open courtyard feel of Myth and Marble invites comparison across different periods, like between the mismatched head of Augustus with a statue of a young man’s torso that was restored in the 19th century as the god Apollo, replete with lyre and serene expression that brings to mind, as the show’s organizers note, the Apollo Belvedere, the statue that art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann touted as the apogee of ancient art.

“Statue of Apollo,” second century CE; head, arms, and lyre restored in the 19th century. Photo: Daniel Orr

“Statue of Apollo,” second century CE; head, arms, and lyre restored in the 19th century. Photo: Daniel Orr

Apollo’s serene visage clashes with that of the emperor Hadrian, whose bust was restored to make it seem that we’re catching Hadrian in motion, like he’s gazing at the wild north from his namesake wall in northern Britannia. The tension around the emperor’s eyes has something in common with the second oldest piece of Myth and Marble, a portrait of a man “known as Euthydemus of Bactria,” which dates to the third or second century BCE.

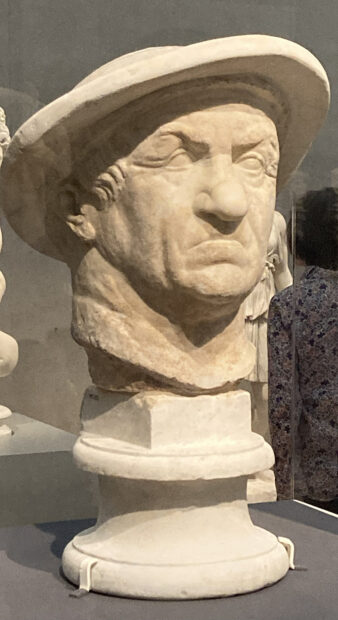

“Portrait of a man known as Euthydemus of Bactria” third or second century BCE. Photo: Daniel Orr

“Portrait of a man known as Euthydemus of Bactria” third or second century BCE. Photo: Daniel Orr

Bactria, which corresponds to present-day Afghanistan, was on the edge of Alexander the Great’s conquests, the very fringe of Greek culture and political influence. Associating this bust with someone with a Greek name from Bactria may not be too far-fetched. This man has the look of someone who has battled it out. His massive neck, jowly frown, and furrowed brow make him look like a mercenary general (regardless of the kind of helmet a mercenary general might have worn: most of his helmet was restored in the 17th or 18th century). The man’s face could not be more different from the serenity of Augustus and Apollo, let alone the serenity of the goddess standing next to him in the gallery. Euthydemus is representative of a new artistic ethic that took hold in the fourth century BCE that tried to make external that which was internal — putting a figure’s character on the outside, and writing their life or inner turmoil across their expressions.

A detail of “Statue of Odysseus Beneath the Ram,” first century CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

A detail of “Statue of Odysseus Beneath the Ram,” first century CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

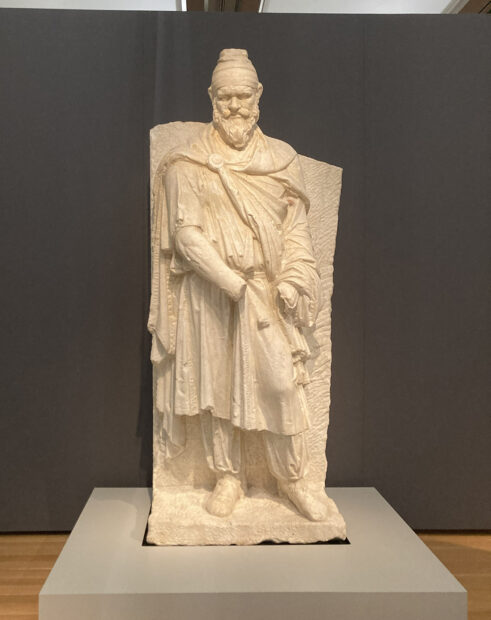

The face of Odysseus clutching his ram for dear life shows the terror and tension at the moment of his narrow escape from the Cyclops’ clutches. The outward signs of fear, not serenity, characterize Odysseus. Similarly, the show’s largest and most enigmatic sculpture offers a study in character. An Unfinished Statue of a Dacian Prisoner may have been intended as part of a monumental commemoration of the Roman conquest of gold-rich Dacia (modern Romania) under Trajan (reigned 98-117 CE), but whatever the intended destination, the sculpture is still not liberated from its surrounding block of marble.

“An Unfinished Statue of a Dacian Prisoner,” second century CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

“An Unfinished Statue of a Dacian Prisoner,” second century CE. Photo: Daniel Orr

The statue’s coarse chiseling attests to its unfinished state, but it instantly called to mind the late works of Michelangelo or Rodin, who found in rough and coarsely chipped marble a visual and textural metaphor for the human spirit. In the case of the Dacian Prisoner, the rough state of the chiseling complements the presentation of his character. His downcast eyes and slightly stooped back present a study in humiliation — perhaps he is supposed to be one of the Dacian prisoners of war who was marched through Rome for Trajan’s triumphal procession. But in his monumental stature that dwarfs the other statues in his vicinity and his distinguished non-Roman bearing, the Dacian Prisoner looks like someone who, like Euthydemus of Bactria and the petrified Odysseus, has endured. The Dacian’s placement in the Piano Pavilion is ingenious. With his unfinished back to a partition, the statue looks toward the line of the restored busts of the Roman emperors and their wives who profited from the conquest. Directly across from the Dacian stands the bronze that the Museo Torlonia believes is one of Augustus’ talented grand-nephew Germanicus.

Bronze statue, possibly of Germanicus, found in Torlonia-sponsored excavations. Note: after the statue was discovered, restorers fashioned a new right leg and support. Photo: Daniel Orr

Bronze statue, possibly of Germanicus, found in Torlonia-sponsored excavations. Note: after the statue was discovered, restorers fashioned a new right leg and support. Photo: Daniel Orr

With the same serene expression of the patriarch (but a slightly different hairstyle that would have helped viewers know that he wasn’t Augustus), this putative Germanicus is frozen in classical youth. The staring contest in which the statues of the heroically-nude Germanicus and the Dacian Prisoner are engaged tells the history of the Roman Empire in a nutshell: one did not have to look far to see the toll of empire. Such a pairing would be hard to find at any museum other than the Kimbell. For museums that specialize in antiquities, a bronze nude is a showstopper, easily occupying an entire gallery, while a statue in a less-than-finished state, like that of the Dacian Prisoner, all too often ends up in an undistinguished corner. Not so in the Kimbell’s presentation of the Torlonia collection..

Myth and Marble also has its share of intimate moments. With several pieces located in a smaller and darker gallery of the Piano Pavilion, the exhibition poignantly ends by making the most of lower ceilings and dramatic lighting. The overriding theme of the last pieces in the show is death, and the objects here, which include several marble sarcophagi, are the kinds of objects that are typical habitués of museum courtyards: too big, too imperial, and too inscrutable for modern sensibilities. While the sarcophagi have their share of conventional motifs, they also possess exquisite restorations, which attest to the great change of taste from 17th century sarcophagal enthusiasm to 21st century nonchalance.

A detail of “Strigilated Sarcophagus with Lions,” 260-270 CE. Note: the right side of the sarcophagus was completely restored. Photo: Daniel Orr

A detail of “Strigilated Sarcophagus with Lions,” 260-270 CE. Note: the right side of the sarcophagus was completely restored. Photo: Daniel Orr

The showstopper sarcophagus of Myth and Marble dates from the middle of the third century CE, and has the look of a phantasmagoric stone chariot carting off its inhabitant to the underworld. With a raked (“strigilated”) pattern on the front, and lions (and incongruously, goats) on the flanks, which are driven by charioteers in relief, this stone casket has the look of what a stage manager of the Colosseum might commission from his local sculptor for his last ride. The sarcophagus too, is a prime example of the chasm between the ethic of imitative restoration that built up the Museo Torlonia and the ethic of authentic preservation that pervades the modern museum. When the sarcophagus was recovered in the outskirts of Rome, its entire left side was defaced. While a contemporary museum would not necessarily reject a half-defaced sarcophagus, it would not display it either (not even in the courtyard), instead shelving it in a voluminous warehouse, never to be seen by anyone outside of a handful of emerging scholars collecting data for monographs on third-century marble sarcophagi or the museum’s own dedicated staff.

“Boy with Dogs,” second century CE. Note: the two dogs as well as the little boy’s arms were restored in the 19th century. Photo: Daniel Orr

“Boy with Dogs,” second century CE. Note: the two dogs as well as the little boy’s arms were restored in the 19th century. Photo: Daniel Orr

As with so much in Myth and Marble, we can be thankful that the many hands who built up this sculptural population did not share that instinct. A fragmented sarcophagus offered an opportunity to hone skills and to try to bridge the gap between antiquity and the present. Were it not for the signage in front of the sarcophagus, I would not have been able to tell which half was restored and which dated from the third century CE. And were it not for the ethic of imitative restoration, I would not be gaping at this showstopper in the first place. In the same vein, the intimate sculpture Boy with Dogs, was more a creation of the 19th century than antiquity. When the chunky torso of the little boy was excavated on the Torlonia estates, he was a headless trunk with no puppy in his arms, no arms, and no dog on the side. Far-fetched a restoration this might be (a chunky baby boy could just as well be the cherubic Cupid or just a chunky baby boy sans canines), Boy with Dogs is a compelling, all the more so considering that the Museo Torlonia didn’t know that most of the sculpture was restored until it began organizing the show.

“Attic Votive Relief,” late fifth century BCE. Photo: Daniel Orr

“Attic Votive Relief,” late fifth century BCE. Photo: Daniel Orr

Hanging on the wall next to Boy with Dogs is the oldest object in Myth and Marble, that is at the same time the least restored object in the show and the most altered. Sculpted in Athens around 400 BCE, this Attic Votive Relief presumably stood somewhere in the city of its origin until it was carved out of its native surrounding and transported to the outskirts of Rome, possibly 600 years later, where it then remained until the 19th century when excavations on the Torlonia’s estates unearthed it. With its top broken off, the relief presents a cipher: it’s only called a “votive relief” because it shares many of the features of other reliefs from the same time and place, but it’s impossible to know what it was for: no writing indicates whether it commemorates the young-looking man at the center of the frieze or whether it offers thanks to the gods for a happy change of fortune. And we can’t even tell what gods are seated above the faceless young man; only their enthroned legs are visible. We can’t even know for sure whether the relief was mostly intact or mostly fragmented when some Roman installed it centuries later by the tomb of Caecilia Metella. Despite its inscrutability, something about the tenderness with which the young man walks his horse and the faithful dog trails behind them spoke to the Roman viewer like it did to me in the Kimbell’s warm glow.

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, “Goethe in the Roman Campagna,” 1787. Städel Museum, Frankfurt. Note: The tomb of Caecilia Metella is the tower at the center of the background. Image courtesy of the Städel Museum

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, “Goethe in the Roman Campagna,” 1787. Städel Museum, Frankfurt. Note: The tomb of Caecilia Metella is the tower at the center of the background. Image courtesy of the Städel Museum

The Attic Votive Relief was excavated near the tomb of Caecilia Metella, which for most of Roman history was one of the most prominent buildings in the city’s outskirts. Two years after Marino Tourlonias died and one year after Goethe came to Rome, Goethe’s fellow German expat, Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein (1751-1829), painted the poet-philosopher pensively lounging in the Roman countryside. We are catching Goethe on the precipice of inspiration, thinking his way to an insight that will lead to Faust or an epiphany on the nature of light or an aphorism about Rome’s population of statues. In the center of the background, on a vertical line with Goethe’s bent knee, rises the medieval-looking tomb of Caecilia Metella, where decades after Goethe’s lifechanging sojourn in the Eternal City, the Torlonia family would buy property, finance excavations, and recover an ancient Greek frieze that was hiding in plain sight and that would go on to become a fragmentary oddity in the Museo Torlonia. It’s a long journey from ancient Athens to imperial Rome, and an even longer one to 21st-century Fort Worth. Texans are lucky they can come get a look.

Myth and Marble: Ancient Roman Sculpture from the Torlonia Collection is on view through January 25, 2026, at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth.