Bexar County is putting new guardrails on how much time county employees can spend responding to open records inquiries from a single requester before labor costs are billed.

County officials say the move is a response to overwhelmingly large requests from a small number of individuals who’ve slowed response times for everyone else.

But the new policy comes as a group of government accountability activists has been calling attention to Bexar County’s spotty compliance with open records laws — and now oppose a solution they say punishes requesters to try to solve the problem.

The Texas Public Information Act allows members of the public access to most government records by requesting them from their respective governing bodies.

In the digital era, however, the number and complexity of requests governmental agencies receive has gone up significantly, said Larry Roberson, chief of the civil division of the Bexar County District Attorney’s office, and the county hasn’t been responding to all of them within the legally required deadlines.

“[The new] policy really is about fairness, transparency and the efficient use of county resources,” Roberson said. ” … [It] protects the county from compliance failures and legal exposure, [by ensuring] consistency, timely responses and resource protection.”

As it stands, the county says it’s been treating all inquiries on a case-by-case basis, offering many records for free and charging for requests that require a lot of labor or printing, Roberson said.

“There is no requirement under the law to provide free access to records,” Roberson said. “[But] we try to be reasonable.”

Going forward, he said, the county is turning to a provision in state law that allows governmental bodies to rein in the amount of time they spend on people who submit frequent or repetitive requests.

Under the new administrative directive Commissioners Court adopted on Tuesday, journalists, scholars and researchers will continue to have the ability to file unlimited records requests.

But people who submit more than 15 public information requests in a month, or more than 36 requests in a calendar year, will be designated as a “zealous requester” and subject to different rules.

The term was used by other government entities, which Bexar County modeled its policy after, Roberson said.

Staff can work on inquiries from such requesters for up to 36 hours in a calendar year for free, with no more than 15 hours coming in a single month, as is outlined in state statute. After that, the county can start charging labor costs, and would need to provide the requester a cost estimate before continuing on with the request.

Roberson said the hourly cost will depend on the type of work, but is regulated by the state. Employees will be responsible for tracking their time.

“It brings structure to a process that’s really been overwhelmed,” Roberson said. “We don’t want the system to be overwhelmed by a few people, we want it to be available to everyone.”

Smoke-filled room?

So far the policy has irked a new group called the Citizen Veteran Journalists of Bexar County, which rejects the county’s exceptions for only traditional media, and believe more people should use the open records process to hold government accountable.

“Restricting ‘media’ status to credentialed outlets in this environment is not neutrality — it is institutional protectionism,” the group wrote in an Oct. 12 email to county leaders.

They refer to themselves online as “a grassroots watchdog organization” dedicated to “exposing waste, abuse, and obstruction in Bexar County government,” and even designed an AI-based public information request writing tool to make it easier for others to submit requests.

In recent weeks, the group has been promoting its use of the Texas Public Information Act to track down emails discussing a meeting of county leaders and San Antonio Spurs executives at Finck Cigars Midtown on Dec. 18 — an event it’s characterized as “backroom deal” strategizing on Project Marvel, but that one attendee contended was a holiday party.

“The timing [of the county’s new open records policy] is unmistakable: it comes immediately after disclosures embarrassing to county leadership,” the group wrote.

Among those in attendance was the county’s then-executive director of economic development, David Marquez, who retired in July.

“I can assure you it was not anything about Marvel,” Marquez said Tuesday. “We have had that holiday cigar meetup for a few years. Purely social gathering of people who enjoy a nice cigar.”

Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai discusses a document with a court official during a county budget work session Tuesday, Aug. 26, 2025. Credit: Diego Medel / San Antonio Report

Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai discusses a document with a court official during a county budget work session Tuesday, Aug. 26, 2025. Credit: Diego Medel / San Antonio Report

Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai, who was invited to the gathering, said through a spokesman that neither he nor any of the judge’s office staff attended.

Sakai told the Report that the new public records policy was part of his greater county modernization and transparency efforts — not an attempt to tamp down on anyone in particular.

“I’m still trying to get county government to comply with the law,” said Sakai, a longtime district court judge who has also been focused on keeping the frequently-sued Elections Department out of court.

“As a result of the records requests that are ongoing, there was no consistent compliance. That’s what we were trying to accomplish [with the new policy],” he said. “This has nothing to do with whoever is filing whatever request.”

An uptick in requests

Officials at the city of San Antonio have also contended with a rising influx of public information requests — more than 86,000 in the 2025 fiscal year alone — including people seeking to review officials’ text messages over months-long windows of time, and YouTube content creators seeking police video footage to dub over with their commentary.

“I’ve been working with open records [for the city] for 13 years,” San Antonio’s Open Government Manager Moraima Montenegro Mcgraw said in an interview Thursday. “When I started, we had 4,000 records that first year.”

Mcgraw now has a 12-member staff — up from two just five years ago — and leans on other city departments’ employees to help.

Both the San Antonio Police Department and the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office now handle their own requests separately from the regular city and county intake process.

But at Bexar County, most other open records requests are filed through a single staff member, Public Information Officer Monica Ramos, who is also the county’s spokeswoman, communication strategist and social media manager.

According to county staff, Bexar County’s open records requests have doubled since 2019, from 2,600 per year to 5,200, with a heavy emphasis on septic system permits and certificates of occupancy. Many of them come from developers, insurance agents and people purchasing property in the county’s unincorporated parts.

There are currently 430 pending requests in the system, county leaders told the Commissioners Court on Tuesday. Each one is supposed to — but currently does not — receive a response within 10 days either providing the records or explaining how long it will take.

“The PIO office over here really just consists of myself and three other assistant public information officers, one graphic designer, and that’s it,” said Ramos, the county’s designated open records manager, who has been in her role since 2013.

“It’s been manageable, but I think now that we’re growing [as a county], it’s probably a good time to start taking a look at [expanding that team],” she said.

A venue for complaints

Unlike the county, San Antonio also has a formal structure to review concerns like the ones the Citizen Veteran Journalists of Bexar County group are trying to bring forward about county officials.

Open records fueled numerous ethics complaints against council members, candidates and city staff members during the 2025 municipal election — some of which turned out to be correct, while others were investigated and dismissed.

The city’s Ethics Review Board vets such complaints with an independent attorney, reviews evidence, determines whether leaders broke the rules, and if so, how they should be punished.

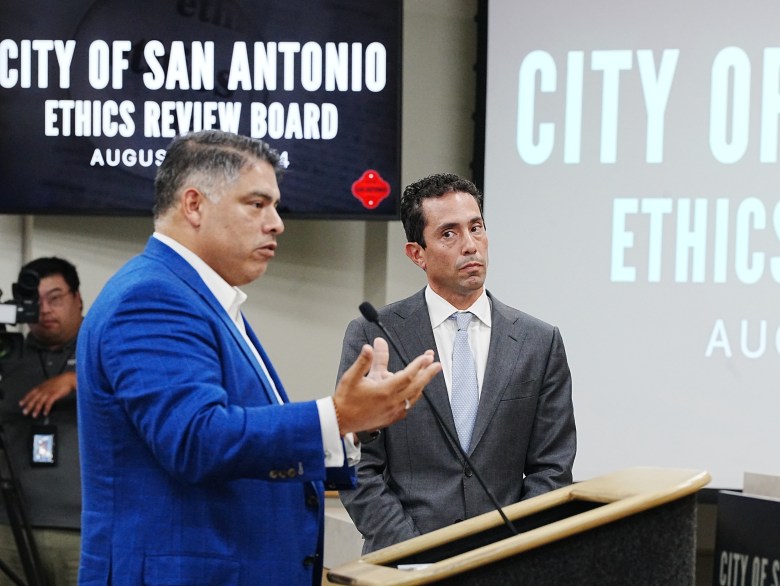

Councilman Marc Whyte (D10) listens to his witness Councilman Manny Pelaez (D8) at the Ethics Review Board hearing to further investigate a 2024 complaint made against him by San Antonio attorney Martin Phipps. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

Councilman Marc Whyte (D10) listens to his witness Councilman Manny Pelaez (D8) at the Ethics Review Board hearing to further investigate a 2024 complaint made against him by San Antonio attorney Martin Phipps. Credit: Brenda Bazán / San Antonio Report

Without anything comparable, those bringing complaints against the county are in a different position.

The citizen journalist group has asked the Texas Rangers to investigate whether the Dec. 18 gathering violated the state’s Open Meetings Act, which requires government entities to do their business in public. Its members have also implored local media to help take up their cause.

The Report contacted the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office to confirm the status of the case. A spokesperson said last week that the department is consulting with the Texas Rangers and the Bexar County District Attorney’s office to determine next steps.

Diego Medel contributed to this report.