Most mornings, the sidewalk outside Sunrise Community Church becomes a kind of waiting room. Before 8 a.m., a few dozen men and women, some pushing grocery carts or dragging luggage, some barefoot with dazed expressions, converge along a bull-wire fence that lines the South Austin property and take seats, inches from a busy stretch of Menchaca Road at the height of rush hour.

Around the corner, kids carrying backpacks exit their parents’ cars and dash behind a tall black fence onto the campus of the public elementary school that serves the surrounding neighborhoods of tidy mid-century ranch houses. And just a block away from Sunrise, a patchwork of tarps, mattresses, and broken office chairs forms a loose encampment under an elevated stretch of U.S. 290.

It’s hard to be indifferent to the grim contrasts if you pass through this area regularly, as I have most days for the past five years. Sometimes the visible despair takes your breath away—seeing a person whose mental or physical health is so hobbled it’s hard to imagine how they survive day to day. Sometimes it’s hard not to feel anger. Anger at a system that’s allowed people to fall so far and failed to offer lifelines. But also anger about what’s happened to my neighborhood, about the trash and blight, about the open drug use and break-ins and the person in the middle of the street taunting stopped traffic. And anger at Sunrise Community Church.

Men and women wait for breakfast at Sunrise Church. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

Men and women wait for breakfast at Sunrise Church. Photograph by Ariana Gomez  Joslin Elementary School sits across the street from Sunrise Church. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

Joslin Elementary School sits across the street from Sunrise Church. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

As the organization in a city of a million people that offers the most comprehensive slate of services to the unhoused—from meals to mail collection to mental health counseling—the church’s Homeless Navigation Center has become an essential resource in Austin. It has also become a magnet, drawing many of the city’s most desperate cases to one neighborhood. Over the past year, the fallout has spread from nearby residents to the Austin City Council and the highest levels of state government. Fairly or not, Sunrise has become a flash point in the debate about how to address the homelessness crisis. The church is either saving people or enabling them. Its pastor, 42-year-old Mark Hilbelink, is either a saint or a menace.

Just last month, that tension sharpened again. A man was arrested for allegedly stabbing another person on the Sunrise property, and in a separate incident, Joslin Elementary students found used needles on the school’s playground, across the street from Sunrise. Austin City Council member Ryan Alter, who represents District Five, which includes Sunrise, has found himself deeply embedded in the controversy since taking office, in 2023. “There’s not a day that goes by that I’m not thinking about something related to Sunrise,” he told me. “It’s the number one time taker by a pretty big margin—just a steady drumbeat that never goes away.”

This summer, Alter’s office announced that the city and Sunrise were working to relocate the Homeless Navigation Center to another site. The move is meant to address frustrations while preserving the center’s ability to serve hundreds of people a day. The announcement only intensified the swirl of questions and feelings I’ve had about Sunrise. When the collateral damage from critically important work harms a community, when is it right to complain? Where’s the line between self-interested NIMBYism and legitimate concern for the social fabric? Is it advisable to offer services for a troubled population directly across the street from an elementary school? Most important, is it possible to even ask these questions without understanding what got us to this point and what actually happens at Sunrise? To begin to work through it all, I started with Hilbelink himself.

Pastor Mark Hilbelink in his office at Sunrise Church on September 4, 2025.Photograph by Ariana Gomez

Pastor Mark Hilbelink in his office at Sunrise Church on September 4, 2025.Photograph by Ariana Gomez

The summer sun was already starting to bake the asphalt as I walked across the Sunrise parking lot to greet Hilbelink one recent morning, just as one of his deputies began addressing the waiting crowd over a loudspeaker. The pastor was unmissable from a distance, with a bushy Abe Lincoln beard, a shaggy helmet of blond hair, and a barrel chest that hinted at his past as a hockey official. He greeted me with a big smile as, just behind me, a police cruiser dropped off a man who had apparently had to be removed from somewhere else. Sunrise would figure out what to do with him.

The Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center and Sunrise Community Church share a warren of low-slung tan buildings linked by a long breezeway that might recede into urban invisibility if not for the crowds and the brightly colored sign that reads “Welcome to Sunrise.” A vending machine dispenses free Narcan, the opioid-overdose-reversal drug, and a black shipping container at the far end of the building contains four climate-controlled bathrooms. Showers are also available on weekday mornings.

Hilbelink led me inside, where staffers and volunteers bustled about, getting the shift started. Every week, dozens of people pitch in at Sunrise—many of them college students studying social work or medicine. They carry large trays of meals, organize donated clothes, or sort mail for the roughly two thousand people who list the facility as their address. A crowded small room with a window facing the yard acts as a distribution hub. “You can’t get food stamps without a mailing address,” Hilbelink pointed out. Perversely, you can’t get on a list for housing without an address either.

A volunteer speaks to a client from inside the mailroom. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

A volunteer speaks to a client from inside the mailroom. Photograph by Ariana Gomez  A vending machine distributing Narcan for free. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

A vending machine distributing Narcan for free. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

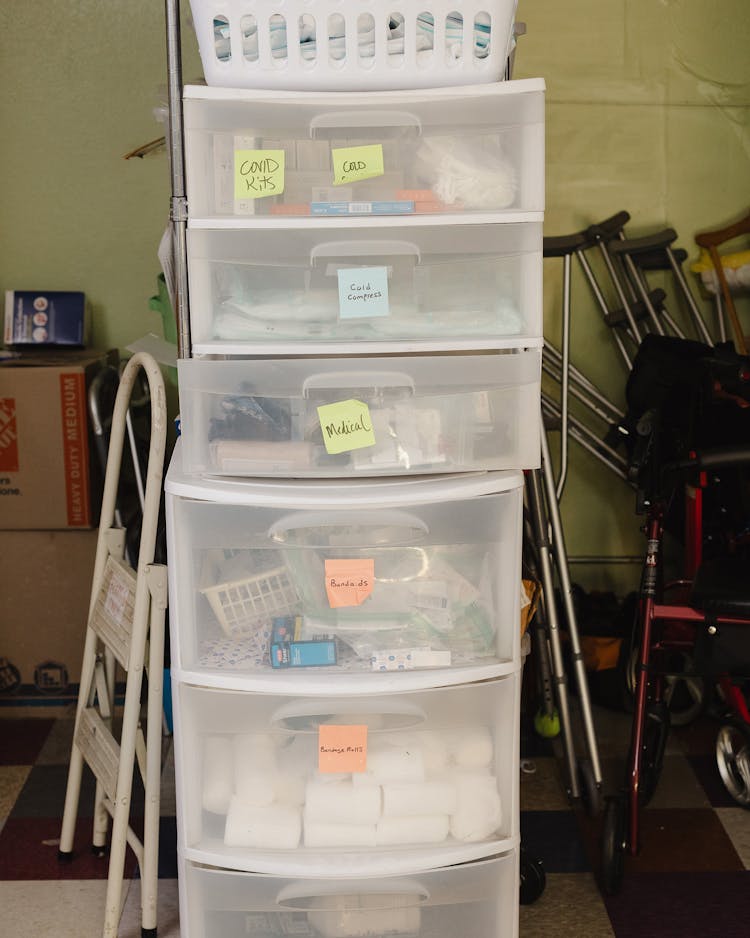

Hilbelink nodded to a wheeled cart full of medicine in the hallway—“the most innovative thing in homelessness in Travis County,” he said. “We find that something in the range of seventy percent of prescriptions that are written for people experiencing homelessness never even get picked up. So trying to help people take their meds correctly has been a big focus of ours. We’ve had people who’ve been out here for a decade, and since they’ve gotten on meds, they’ve never been back to jail, never been back to an ER.”

What looks from the street like a loose crowd in the Sunrise yard is in fact several lines leading to tables where people can access one of multiple services, such as help applying for housing assistance. The center’s clients can also get referrals to mental health providers and substance-abuse treatment, and twice a week, there’s a medical clinic on-site. “One of the major things people don’t get about homelessness is that you’ve typically got to go to ten different places to get all these different services,” Hilbelink told me. “To be able to get them all in one location skyrockets the chances of it actually working.”

Indeed, by integrating a full array of assistance in one location—come one, come all, no appointment necessary—Sunrise has become widely acknowledged as the single most effective organization in Austin at lifting people out of homelessness, and arguably in the state. It has received well over $1 million in public funding in the past year alone, from a combination of City of Austin, Travis County, and federal HUD programs, along with private donations from the likes of billionaire John Paul DeJoria, who was formerly homeless himself.

In 2024, the Navigation Center served nearly 20,000 people, served almost 100,000 meals, and helped more than 1,200 find housing. That’s 1,200 people in a city whose homeless population, according to the Ending Community Homelessness Coalition, was about 6,200 last year, the highest per capita homeless count in the state.

Texas monthly Favorites

Hilbelink tracks those numbers like a CEO watching the bottom line, and his language at times veers into entrepreneurial jargon, with talk of scalability, efficiency, and metrics-driven decisions. “Homelessness is fundamentally a math problem,” he said as he led me past a cellphone-charging station and into the church sanctuary, where a couple of clients were using a makeshift laptop computer lab and a mother led her daughter toward a courtyard playground. “If you’ve got more people flowing in than you have flowing out, you’re always going to have more people on the street. The trick is how do we get more people flowing out than flowing in.”

Clothing donations ready to be distributed to clients. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

Clothing donations ready to be distributed to clients. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

Hilbelink didn’t set out to be a social services entrepreneur. A native of Orange City, Iowa—a rural area in the northwest corner of the state where, he says, there were “more pigs than people”—he experienced poverty and lived on food stamps at an early age. “I’ve eaten some government cheese,” he told me. After attending Calvin Theological Seminary, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, he worked briefly in Detroit, at that city’s nadir, but he had had hardly any experience with large cities before he got a call, in 2009, to take over as the head pastor at Sunrise.

He was in his mid-twenties and thought he was coming to be the groovy young pastor, the guy in jeans splitting his time at the pulpit between sermonizing and strumming catchy guitar riffs. Sunrise already had a reputation as a place that was open to “folks who wouldn’t fit at normal churches—single moms, folks who were gay, things like that,” Hilbelink said. And the church had long hosted recovery groups for people struggling with substance use disorder. But in the big picture, in Hilbelink’s mind, his work at Sunrise would amount mostly to “regular church things.”

Shortly after he arrived, though, an increasingly visible homeless population in downtown Austin led police to start more regular sweeps of encampments there, which effectively pushed some of that population to other parts of the city—especially where highway underpasses, wooded areas, and proximity to major bus routes could make life a little easier. Few parts of Austin have a greater confluence of those factors than the area near Sunrise, about four miles south of downtown and flanked on one side by the woods along Williamson Creek and another side by the Barton Creek Greenbelt, one of the city’s natural gems, offering nearly one thousand acres of forested wilderness laced with trails and, at certain times of year, refreshing swimming holes and waterfalls.

For the young pastor, the moment was a major crossroads—for his life, for his church, and for his community. There were “significant voices” arguing that homelessness wasn’t Sunrise’s problem, he remembers. But on the other hand, he thought, “We have this Bible, and it tells us we’re supposed to do something and not turn a blind eye.”

The Navigation Center launched in 2015 and has steadily expanded its suite of services ever since. When the COVID-19 pandemic forced many of the city’s other providers to curb their offerings because they weren’t allowed to assist people indoors, the number of clients taking advantage of Sunrise’s mostly outdoor services surged—quadrupling in 2020. The homeless population around the church also surged. The city had legalized camping in most public spaces in 2019, and now an enormous tent city rose under the highway near Sunrise and began to spread out into surrounding blocks.

The city reversed its camping ordinance in 2021 and started a long whack-a-mole game of forcing people to dismantle their shelters only to see them pop up across the street. As Hilbelink watched all of that happen, it only strengthened his conviction that he was doing the right thing—and that Sunrise was more necessary than ever. Today the organization has almost one hundred employees and an office downtown. It runs a hotline twelve hours a day through which people can access some services remotely, a program that won a contract with the City of Austin.

Diane Holloway passes a cup of freshly made coffee to a client. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

Diane Holloway passes a cup of freshly made coffee to a client. Photograph by Ariana Gomez  Bins full of medical supplies. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

Bins full of medical supplies. Photograph by Ariana Gomez

“Mark is fascinating and inspiring and smart as a whip,” said Diane Holloway, a longtime volunteer at Sunrise, when we met for coffee one day this summer. “Inside that giant head, there’s a lot of information and inspiration.” Holloway, who lives near Sunrise, first started working with the homeless after she took a buyout and retired from her first career, journalism, back in 2009 and began working with the Trinity Center downtown, another service provider that has historically had a narrower mission than Sunrise’s. When the pandemic forced Trinity to pause its mostly indoor operations, she stopped by Sunrise to introduce herself and ask what she could do to help.

Today Holloway works in what she calls “humanitarian operations” at Sunrise—assisting clients with food and clothing and basic hygiene needs. It’s a demanding job, physically and emotionally, but the thing that frustrates her the most about it is people who wish Sunrise weren’t there. “The neighborhood is afraid of things they don’t know and people they’ve never met or talked to,” she said. “They just say, oh, their property value’s going down. Well, sorry, you bought a house here.”

When she wants to recharge, Holloway told me, she draws inspiration from the people in line at Sunrise. “It’s become that they’re my people, my tribe. So many of them are so optimistic. Somebody who’s been homeless for six years says, ‘It’s going to get better. It’ll be okay.’ I think a lot of people should spend more time thinking about what disgusts them about homeless people. They’re in your way on the sidewalk? Walk around. It’s half a block. You’ll survive.”

Among the neighbors I’ve talked to about Sunrise, Holloway is an outlier. “The people we see every day appear to be hardcore tweakers and not so much honest people down on their luck,” complained one neighbor who used to live over my back fence—a long-haired folk musician who would be tough to characterize as a heartless NIMBY. Reddit threads overflow with angry comments. “That place is terrifying.” “Completely ruining the neighborhood.”

In the past couple of years, Hilbelink has taken to holding community “de-escalation” sessions, at which he gives presentations about the center’s success metrics. He makes his case to local TV crews when they report on anything related to homelessness. Sunrise has a cheerful social media profile that celebrates its milestones and showcases volunteers. And the center sends crews out to pick up trash within a two-block radius of the church. But the public relations battle remains challenging when people feel unsafe in the area. Early this summer, I was passing under the nearby highway on a motor scooter when a man walking down the middle of the road started swinging a baseball bat—about a foot from my head as I swerved to get around him.

The outcry about Sunrise has hardly been limited to the immediate area, and last November, Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a lawsuit against Sunrise seeking to prohibit it from operating within one thousand feet of a school or playground. The filing, which cites 911 calls, police reports, and parental complaints from Joslin Elementary, reads like dystopian fiction. Using vivid—at times lurid—detail, the complaint positions Sunrise as fostering a level of disorder and danger that outweighs the good being done there.

“In South Austin, a once peaceful neighborhood has been transformed by homeless drug addicts, convicted criminals, and registered sex offenders,” it begins. “These people do drugs in sight of children, publicly fornicate next to an elementary school, menace residents with machetes, urinate and defecate on public grounds, and generally terrorize the surrounding community. . . . And everyone involved knows who is responsible: Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center.” In 43 pages, the document describes one alarming incident after another: a rape in the park; a man cutting himself and drawing on the sidewalk with his blood; and people exposing themselves to children near the school.

I recognize some of the references. Everyone in the neighborhood has seen the man with the machete, Rami Zawaideh. He lives in the woods along Williamson Creek, has been in and out of police custody multiple times, and has become a fixture in the local news coverage of homelessness. Hilbelink knows all about Zawaideh, too, but he told me the man has never come to Sunrise for any services. In any case, he said, “a significant number of people” are banned from coming back to Sunrise after previous incidents. The center has criminal trespass notices against some of them.

A school bus passes by Sunrise Community Church.Photograph by Ariana Gomez

A school bus passes by Sunrise Community Church.Photograph by Ariana Gomez

On one hand, Hilbelink distancing himself from the most problematic people in the homeless community near Sunrise makes sense. If they’re not part of the Sunrise clientele, can he really be responsible for them? On the other hand, if Sunrise is part of the reason the homeless community has grown in the area, doesn’t it bear some responsibility for the impact on public safety?

When I asked Holloway, she bristled at the suggestion. “It’s very unfair to blame a little group of people that have turned into the number one homelessness-services provider in Travis County, to blame us for all the negatives involved with homelessness,” she said. “We’re trying to solve the problem; we’re not just offering food and coffee.” She maintains that many who seek help at Sunrise arrive on city buses at the transit station two blocks from the church—and then get back on buses to return to other parts of Austin.

Sunrise’s public statement at the time of Paxton’s filing emphasized that churches are protected under the First Amendment and the U.S. Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act “to do work that is an expression of their religious practice”—such as serving the poor. The AG’s complaint and other state-level efforts to target Sunrise have focused on its proximity to a school. Two bills that were introduced in the 2025 legislative session sought to limit where “homeless services” can be offered. One prohibited them within 1.5 miles of any school, university, or playground. The other drew the line at 1,000 feet from schools, parks, and residential areas. Both bills stalled in House committees after widespread criticism from the nonprofit community pointed out that the legislation would inadvertently cripple other vital service providers.

A volunteer serves clients lunch.Photograph by Ariana Gomez

A volunteer serves clients lunch.Photograph by Ariana Gomez

In Austin, for instance, one temporary-housing operation for single mothers transitioning out of homelessness, the Jeremiah Program, is intentionally located near an elementary school so that kids can walk there and back. “Intuitively, it seems so simple,” said Councilman Alter. “Why would you want any homeless service near a school or a park? But you have to be very careful.”

Paxton, meanwhile, renewed his campaign against Sunrise after the recent stabbing and needle incidents, issuing a letter to the court demanding the Navigation Center be shut down immediately. A press release from the AG’s office denounced the “radical Austin judge” and “dangerous vagrant shelter” for what it portrayed as endangering schoolchildren. The judge, Aurora Martinez Jones of Travis County District Court, has so far declined to grant an injunction, leaving the case to proceed on a slower track. But the showdown makes clear the fight over Sunrise is far from cooling.

Clean-cut and boyish, Alter is a 35-year-old Harvard-educated lawyer and Austin native who was born just a few blocks from Sunrise, at St. David’s South Austin Medical Center. He calls Sunrise one of his district’s greatest assets and biggest headaches. “If you took Sunrise out of the equation, we would be in big-time trouble,” he said one day recently, at a small meeting table in an upstairs office at Austin City Hall. “That’s one piece of this story. The other piece, the cautionary tale, is that if you don’t plan for the kind of growth they’ve seen, you can end up with a very bad situation.”

Alter admires Hilbelink’s conviction. But as a well-trained and ambitious politician who has worked for three state senators, he is a seeker of compromises and solutions. “I think if they knew eight years ago where they were going to be today, maybe we could have gone to them and said, ‘Hey, love what you’re doing. Let’s find a spot to really set you up for success.’ Instead, now we’re trying to constantly play catch-up and just deal with the situation.”

In Alter’s view, the city should have five to ten homeless navigation centers like Sunrise’s spread throughout the region—ideally one for each of the ten council districts—and each could serve a few dozen people per day, rather than a few hundred. In April, the city’s Homeless Strategy Office released a $100 million plan that included a provision for two additional navigation centers—possibly by expanding the offerings at existing facilities such as the Trinity Center downtown and the Charlie Center, in North Austin, where Hilbelink is already on the board.

Crucially, the city’s plan also called for relocating Sunrise, and Alter stepped in to work on that. It wasn’t an easy task to find the right spot—which should be easily accessible from major bus lines but not in a residential area or close to a school or park, he explained. “There are very few places like that in the entire city.” Last week the city announced it had selected a possible location for a new navigation center and solicited public feedback before it agrees to purchase the building, a former motorcycle showroom off Interstate 35, about four miles from Sunrise and just a few doors down from a city-owned shelter.

If the plan goes through, following a city council vote in October, the city will buy the roughly $4 million building and lease it to an operating partner—not necessarily Sunrise—with a goal of having it up and running in the spring. Mayor Kirk Watson, in a statement, said the arrangement “will maintain stronger oversight and accountability than current navigation center models that operate independently and have admittedly been the target of complaints.”

When news of the potential replacement navigation center first surfaced in the local press in late June, the same social media threads that had lamented the crime and blight around Sunrise rejoiced. “As a former volunteer there, all I can say is, thank god,” a Redditor on r/Austin said. “Best news I’ve heard all year!” said another.

But even if Sunrise ends up operating the new center and moves most of its services there, certain clients might still be served at the current location—such as families with children, who make up as much as 34 percent of the homeless population, according to a 2024 study. “One in three calls to our hotline is now a family with children,” Hilbelink told me. Teachers are often the ones to identify the families, when kids come to school unbathed and fall asleep in class. Once Sunrise gets a family into the system, its members are often easier to house than other clients, he says. “People are more willing to help a parent with kids than a single adult.”

Clients line up each morning to receive services outside Sunrise Community Church.Photograph by Ariana Gomez

Clients line up each morning to receive services outside Sunrise Community Church.Photograph by Ariana Gomez

One of Hilbelink’s favorite statistics to share with visitors is that there are roughly three thousand churches in the Austin area, and that “if every church in Austin served two homeless people, you wouldn’t need day centers. Unfortunately, Christianity has adopted a kind of exceptionalism, a club mentality,” he said, “and that’s really sad.”

Hilbelink also likes to note that Austin has far more vacant housing units today—as many as 50,000, according to recent estimates—than people experiencing homelessness. The problem is that the vacancies are heavily skewed toward the luxury segment of the market, so they’ll never be available to the unhoused. As a result, there’s a waiting list for available units, and even just getting on the list is anything but simple. First, an applicant has to get assessed through the city’s “coordinated entry” system, which ranks people by need—not by who’s been waiting the longest. Required documents can include an ID, Social Security card, and proof of homelessness—things many people don’t have. Even after being matched with a housing program, people face background checks and other hurdles before a unit becomes available.

This June, Sunrise announced that for two months in a row, it had placed more than one hundred people into twelve-month leases via a program called Wayfinder, which it first piloted in 2022 and which has won partial funding from the city. In partnership with a nonprofit called Housing Connector that works with landlords, via a Zillow-based platform, to remove barriers such as strict credit checks and high deposits (in exchange for incentives such as damage coverage), Wayfinder focuses on rapid-response housing.

Wayfinder is the kind of scalable solution that has become much of Hilbelink’s focus as he has begun to leave daily operations at Sunrise to his staff. “The majority of our operation is now digital,” he told me. The hotline, which also debuted in 2022, now helps more people navigate the housing system than the physical location does. A third innovation was on display in the sanctuary at Sunrise the day I visited: a prototype of a glassed-in pod with a video screen, from which clients can talk to caseworkers remotely and privately. Hilbelink hopes to deploy pods around the city to libraries, hospitals, shelters, and jails, among other locations.

Sunrise has also found itself to be an effective venue for studying homelessness, and it has partnered with University of Texas at Austin researchers for various studies, such as one that tracked clients’ sleep with Fitbits and found that almost nobody was getting more than two hours at a time. Another study, with the pharmacy school at UT, looked at medication adherence and homelessness outcomes.

As Hilbelink talked, I thought about my preconceived notions about him, and about this place. I had come expecting to meet a kind of punk rock pastor, a guy whose defiance was as notable as his devotion to the cause. And that might be roughly accurate. But what I hadn’t expected was a start-up-style CEO, the Mark Zuckerberg of homelessness services, with a clear “move fast and break things” philosophy as well as a relentless focus on maximizing what every freshly minted MBA calls total addressable market.

Hilbelink told me early on that he thinks a church should reflect its community—and that that was what drove him to enter homelessness services in the first place. “We didn’t start Sunrise Navigation Center because it was really fun to do homeless services—we started it because homelessness was bad in that area,” he said. If the Navigation Center’s relocation simply exports the problems surrounding Sunrise to another pocket of the city, he’ll end up having to revise part of that argument.

No matter how ugly the process has been or how worked up people get about the spillover effects, homelessness around Sunrise Community Church has dropped significantly. Hilbelink deserves some of the credit for that, no doubt—as do political pressure, frequent police sweeps, and tall razor wire fences blocking prime camping spots. Now Hilbelink is leveling up and redefining his community as something much wider than a corner of South Austin. As his neighbor, I’m rooting for him. And for the relocation plan.

Read Next