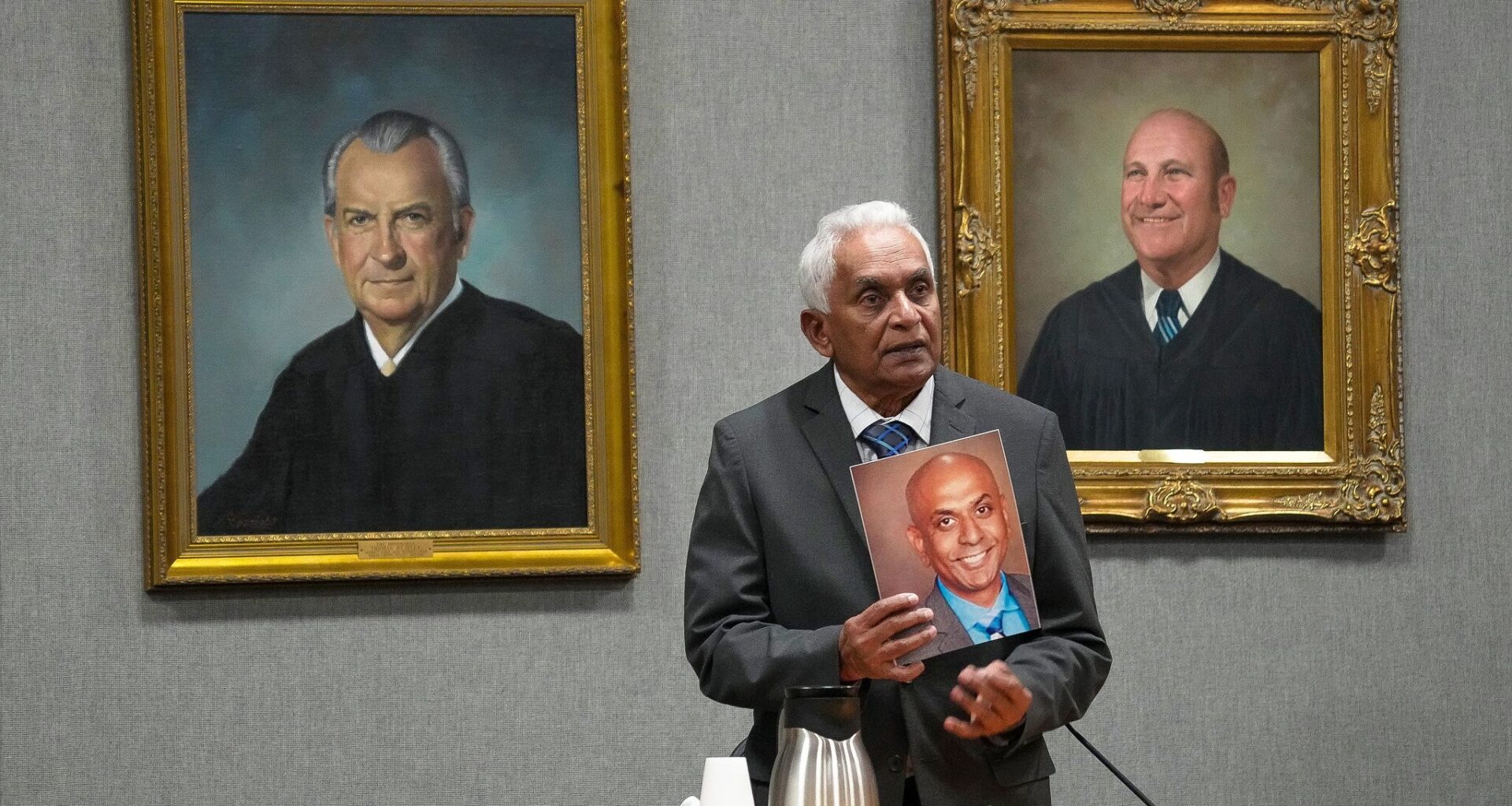

Denzil DeSilva holds a picture of his late son, Mauris DeSilva, while testifying Wednesday, the first day of the sentencing hearing for Austin police officer Christopher Taylor, about how his son’s death has affected his life. Taylor was convicted earlier this month of deadly misconduct in the 2019 shooting of Mauris DeSilva.

Ricardo B. Brazziell/American-St

In December 2024, an all-Democrat court in Austin was set to hear the appeal of an Austin police officer convicted of shooting and killing a mentally ill man when an order arrived from the Texas Supreme Court.

The three-page directive instructed the Third Court of Appeals to transfer the first 15 cases it received Dec. 4 or after to the Seventh Court of Appeals in Amarillo. The order was part of a routine process the state’s highest civil court uses to balance caseloads among the state’s 14 regional intermediate appeals courts.

Article continues below this ad

But the transfer gave what legal experts say proved to be a significant advantage to former Austin police officer Christopher Taylor: It meant his politically charged case was moving from a liberal-leaning court to far more conservative jurists in the rural Texas Panhandle.

For his legal team, it was an early Christmas gift.

“I felt like we would have a better shot,” said Richard Wetzel, Taylor’s attorney. “I was pleased.”

Austin attorney Chris Perri, who specializes in post-conviction appeals and closely followed the case, said he immediately believed the transfer to an all-Republican court 500 miles away would favor Taylor.

Article continues below this ad

“I would think that would be the best news I could get if I were a police officer defendant,” he said. “Normally a defendant would be scared — they are going to be harder on me. They are going to lock me up and throw away the key.”

Last month, a three-justice panel gave Taylor a best-case-scenario ruling. Not only did the justices overturn his conviction, they took what experts say is a highly unusual step in deeming Taylor acquitted, ruling that the Travis County jury that convicted him lacked sufficient evidence.

How it all played out

Taylor had been sentenced to two years behind bars in the death of Mauris DeSilva, who had a knife when Taylor and another officer fired at him in a downtown condo tower in 2019. The court’s ruling allowed the state licensing agency for police officers to restore his employment eligibility last week, and Police Chief Lisa Davis is now considering reinstating him.

Article continues below this ad

The Seventh Court of Appeals courtroom in Amarillo

Seventh Court of Appeals

Travis County District Attorney José Garza blasted the Dec. 30 decision, calling it “absurd” and saying “The conservative Amarillo-based 7th Court of Appeals judges think they know better than the Travis County jurors who heard the case and convicted Taylor.”

It’s unclear why Garza did not attempt to block the transfer, even though state rules allow prosecutors to file a motion explaining why a case should remain in its home court.

Related: José Garza promised police reform. His solution to an Austin fatal shooting ‘strains credulity’

Article continues below this ad

Garza’s office said it “will refrain” from responding to an inquiry from the American-Statesman about whether the lack of a challenge was intentional.

The Austin-to-Amarillo transfer was conducted through a century-old process administrators call “docket equalization,” used to prevent some courts from being overburdened while others carry a lighter workload. About 5% of appeals filed with the courts in the past two years were transferred, according to the Texas Office of Court Administration.

The system has been widely debated over decades. Some attorneys say that it prevents excessive wait times for rulings from busy courts, but others say it plucks cases from judges elected by voters in the state’s 14 appellate districts, making the courts less democratic.

Dallas attorney Wade Glover, who wrote a 2008 paper on the topic for the Texas Tech Law Review, said the process also creates unpredictability about where and by whom cases will be heard and can turn justice “into a crapshoot.”

Article continues below this ad

A century-old system

Austin police officer Christopher Taylor leaves the courtroom during his deadly conduct trial in Judge Dayna Blazey’s 167th District Court at the Blackwell-Thurman Criminal Justice Center Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. Taylor is charged with deadly conduct for his role in the death of Mauris DeSilva in 2019.

Mikala Compton/American-Statesma/Austin American-Statesman

The transfer of Taylor’s case was part of a process that dates back more than a century.

Texas created its appeals courts at a time when the Legislature did not allow individual courts to add justices as workloads grew. Instead, lawmakers created new courts as population centers expanded. That history explains why Houston has two intermediate appeals courts: the First Court of Appeals, established in 1892, and the Fourteenth Court of Appeals, created in 1967.

Article continues below this ad

A constitutional amendment approved in the late 1970s eventually allowed courts to add justices. But by then, the state had already adopted docket equalization as a way to manage uneven workloads, said Austin-based attorney Jason LaFond, an appellate specialist and former assistant state solicitor general.

“That machinery takes the pressure off the Legislature to create new judgeships and regional courts,” LaFond said. “They probably don’t feel a strong need.”

Over the years, the Legislature and the state Supreme Court have revised laws and rules governing transfers to address complaints from attorneys and litigants.

Lawmakers, for example, authorized appellate courts in 1999 to hold hearings by teleconference to reduce travel burdens.

Article continues below this ad

The Supreme Court’s current rules, adopted in 2006, say the high court may transfer both civil and criminal cases based on the number of filings in each court compared with the statewide average per justice, adjusted for historical trends.

Texas Office of Court Administration spokeswoman Megan LaVoie said agency staff members help the Supreme Court with data collection and calculation of transfers when they are needed. Orders are typically issued at the start of each fiscal quarter, in September, December, March and June.

Taylor’s timing proved especially favorable.

To avoid immediate incarceration, Taylor filed his notice of appeal on Dec. 3, the same day a judge handed down a two-year sentence. Three days later, the Travis County District Clerk notified the Third Court of Appeals of the filing, and the court acknowledged receipt that day.

Article continues below this ad

About three weeks later, the Supreme Court issued an order transferring the first 15 Austin cases received on or after Dec. 4 to Amarillo. The next 18 were sent to El Paso. The same order reassigned dozens of cases statewide, including appeals from Fort Worth, San Antonio and Waco.

Did the transfer matter?

Council approaches the bench during Austin police officer Christopher Taylor’s deadly conduct trial in Judge Dayna Blazey’s 167th District Court at the Blackwell-Thurman Criminal Justice Center Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2024. Taylor is charged with deadly conduct for his role in the death of Mauris DeSilva in 2019.

Mikala Compton/American-Statesma/Austin American-Statesman

Wetzel, Taylor’s appellate attorney, said he does not believe conservative ideology drove the Amarillo court’s decision.

Article continues below this ad

“I think any conscientious appellate judge among any of the 14 courts of appeals would have reached the same result,” he said.

Perri strongly disagreed. Judges, he said, routinely interpret the law through the values of the communities where they live and are elected.

“Christopher Taylor starts further up the playing field than most criminal defendants,” he said. “They are going to be suspicious of the liberal prosecution and liberal jury who convicted him.”

Perri said the Amarillo court acted as a “13th juror,” selectively interpreting the evidence to justify an acquittal. He said the opinion appeared to ignore key facts, including that DeSilva had no history of violence toward others, and that another officer at the scene deployed a Taser.

Article continues below this ad

“[Y]ou are just seeing the bias drip off the page when you read that opinion,” he said. “It is just evidence of a very biased judiciary.”

‘The best of a difficult situation’

Even so, legal observers say the case may ultimately be decided by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, whose all-Republican judges would likely have reviewed the outcome regardless of which intermediate court handled the appeal.

State leaders have periodically floated proposals to overhaul Texas’ appellate system, including shrinking the number of courts, adding justices or redrawing judicial districts based on population. None have gained traction at the Capitol.

Article continues below this ad

To Glover, the Dallas attorney, the need for a case redistribution process is proof the system is flawed.

“[T]he locations and jurisdictions of the appellate courts are antiquated, having been substantially in place before the Great Depression,” Glover wrote. “If the Texas appellate courts were better organized and located to meet the needs of Texas citizens of the 21st century, dockets, for the most part, would not need to be equalized.”

Absent significant efforts to review and possibly overhaul the current court structure, LaFond said, the transfer system remains the state’s most practical option.

Article continues below this ad

“It is making the best of a difficult situation,” he said.