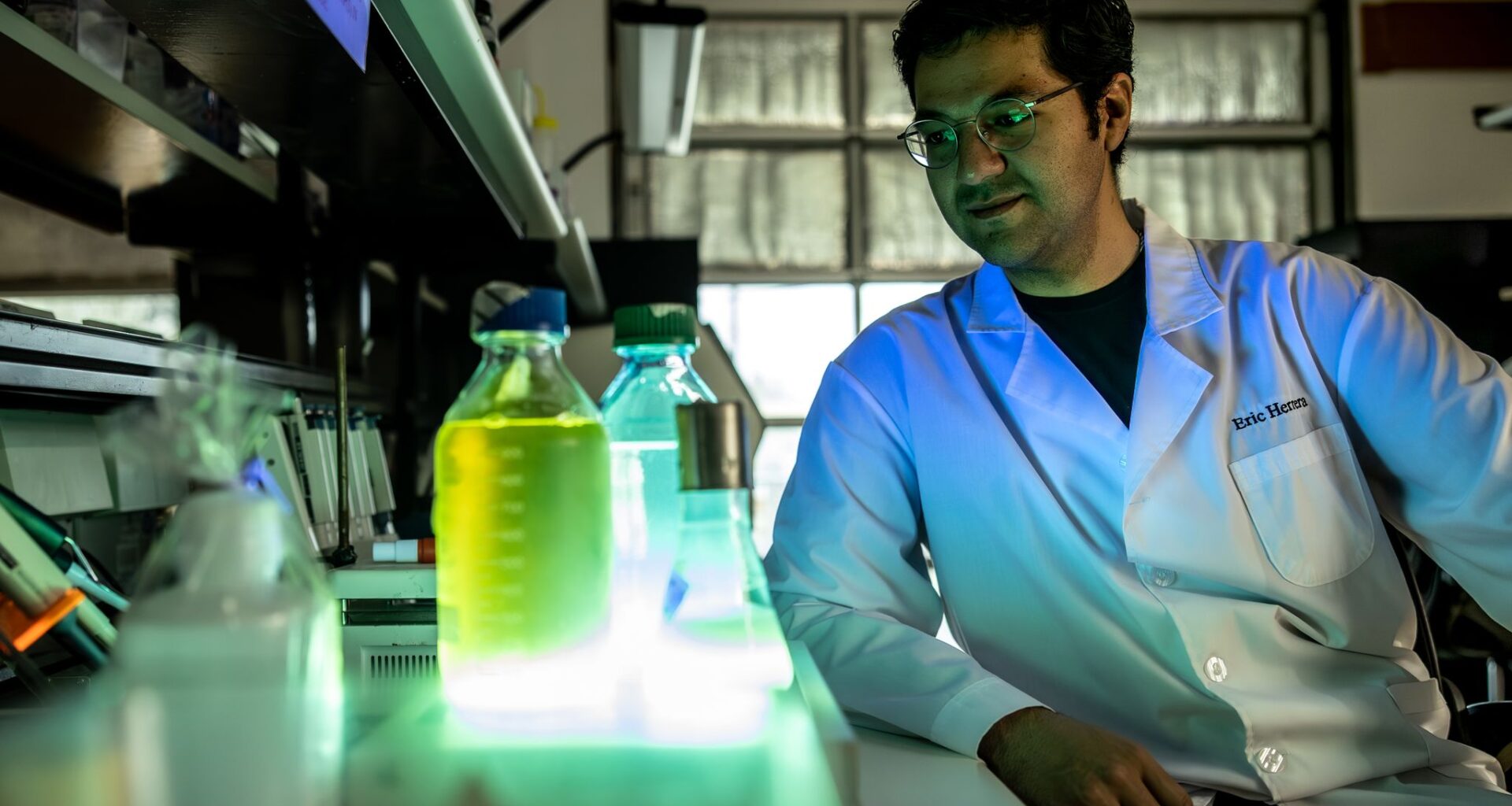

Eric Herrera discovered and, with MavericX co-founder Jesse Evans, optimized a bacteria from the Arctic that he’s using to cultivate faster, safer and more sustainable extraction of critical metals. Herrera is pictured in the lab at Maverick X in San Antonio. It’s moving this year to Austin.

James Lewis/Contributor

There was no guarantee that Eric Herrera would discover anything notable while scouring the Arctic sampling water, rocks and anything else he could swab or draw up in a syringe while on an Explorers Club expedition in 2022.

“I got lucky,” he said.

Article continues below this ad

Eric Herrera was recently listed on the Forbes 30 Under 30 List. Herrera discovered and optimized a bacteria from the arctic that he’s using to cultivate faster, safer and more sustainable extraction of critical metals from oil and gas. Herrera is pictured in the lab at Maverick X in San Antonio

James Lewis/Contributor

Eric Herrera was recently listed on the Forbes 30 Under 30 List. Herrera discovered and optimized a bacteria from the arctic that he’s using to cultivate faster, safer and more sustainable extraction of critical metals from oil and gas. Herrera is pictured in the lab at Maverick X in San Antonio

James Lewis/Contributor

Eric Herrera was recently listed on the Forbes 30 Under 30 List. Herrera discovered and optimized a bacteria from the arctic that he’s using to cultivate faster, safer and more sustainable extraction of critical metals from oil and gas. Herrera is pictured in the lab at Maverick X in San Antonio

James Lewis/Contributor

A test tube of an ambiguous substance collected at the magnetic North Pole contained a bacterium that’s since become the catalyst for MaverickX, the company he co-founded with Jesse Evans. Using the specimen, the San Antonio duo has found a faster, safer and more sustainable method for mining critical metals and extracting oil and gas.

READ NEXT: Texas A&M researchers develop first known metallic gel

The bacterium has a peptide that dissolves rock and allows it to get the iron needed for respiration. But MaverickX discovered a commercial use for the natural and nontoxic green substance.

Article continues below this ad

“It doesn’t matter what the rock contains, whether it’s precious metals, rare filaments, or oil and gas,” Herrera said. “It breaks the rock and it comes out.”

The business uses retrofitted brewery equipment to produce bacteria rather than beer. In a glass jar, Herrera shows the yellow chemical that emits a fluorescent glow when exposed to ultraviolet light.

Now, the company has optimized the bacterium and produces it at scale — an accomplishment that recently earned Herrera and Evans a place on the Forbes 30 Under 30 Green Energy & Technology list.

Article continues below this ad

But they’re not done looking for more breakthroughs.

Eric Herrera went to Antarctica last month for another expedition to gather more samples to analyze at the company’s lab in San Antonio.

Maverick X

In early December, Herrera embarked on an expedition to Antarctica. Similar to his trip to the Arctic, he was set to swab and syringe anything that looked promising, secure the findings in test tubes and collect as much information as possible — salinity, pressure, temperature — about where samples were found.

“We bring them back to the lab and actually extract the DNA here in San Antonio,” Herrera said.

Article continues below this ad

But San Antonio won’t be the operation’s headquarters for much longer. The MaverickX team of 20 will double this year as the company expands to a new site in Austin. Herrera plans to bring in new people from every side — scientists, business advisers and sales experts.

S.A. to Austin

The potential for new science, innovative technology and startups is not scarce in San Antonio, Herrera said, but support from the city seems to be. During the first phase of testing in 2024, San Antonio was awarding grants for businesses that brought in federal funding. The city said it would match grants, endowing up to $50,000.

RELATED: In a giant UTSA lab, professors delight in breaking things for science

Article continues below this ad

The U.S. Department of Energy awarded MaverickX its maximum grant: $300,000. He said he went to the city of San Antonio for the promised matching capital.

“The city told us that there wasn’t funds available,” he said.

When the business was awarded another grant, this time for $2.6 million for its Phase 2 testing, MaverickX decided to pivot to Austin. Herrera said he didn’t want to spend money in a city that wasn’t supporting the company.

MaverickX co-founder and Chief Operating Officer Jesse Evans, left, and co-founder and CEO Eric Herrera in their lab in San Antonio. Soon, it’s moving operations to Austin.

Maverick X

There are business opportunities in cutting-edge science coming out of the University of Texas, Herrera said, and a strong work ethic in San Antonio. But lack of financial backing hinders success anywhere.

Article continues below this ad

“There is that capability here, there is that capacity there, there is the people here,” Herrera said of San Antonio and Austin. “There just isn’t so far that support framework that there is in Austin.”

Financial support is key to MaverickX as it works to scale up. It currently has 14 mining partners that mostly focus on extracting copper and gold in every continent except Antarctica and Europe. The business is working with 30 oil and gas companies.

Now, he’s selling the product to two different industries: oil and gas and mining and metals. Critical minerals excavated through mining are the “building blocks of modern technology,” the World Resources Institute said, supplying necessary resources for electronics and clean energy technologies.

READ MORE:City of San Antonio cracks down on metal and automotive recyclers

Article continues below this ad

Shortening the timeline

It takes a global average of 17.9 years to transition from the discovery of copper into production, according to a S&P Global Report. In the United States, that expands to almost a 29-year timeline, due to the permitting process and study phases.

MaverickX eliminates the need to dig the traditional mine pit. Instead, it deploys its faster and more environmentally friendly extraction method in situ recovery.

Eric Herrera is seen this month in the lab at MaverickX in San Antonio.

James Lewis/Contributor

Using a small pole, they frack the ore body. Their chemical concoction containing the bacterium is then pumped in, liquefying the rock underground. It then pumps the mineral-rich solution to the surface for processing, without the need for physical excavation, Herrera said.

Article continues below this ad

For businesses, Herrera said, the product saves about 25% of capital expenditure. Insurance premiums additionally go down because it’s a safer work environment, he said.

One mine MaverickX works with does heap leaching, a process of metal extraction that pours acid over stacked rocks, allowing the metal to leach out. The mounds are 200 yards by 300 yards, spreading 2 kilometers.

“If we want to be big players, we need to reach that level of size,” Herrera said.

RELATED: Oil, LNG exports fuel record-setting first half at Corpus Christi port

Article continues below this ad

MaverickX’s roots

The foundations for the business were laid after Herrera graduated from Washington and Lee University in 2020 with a bachelor’s degree in neuroscience. It was a “weird time,” he said, with limited job prospects at the start of the pandemic. He was considering starting graduate studies at Harvard University when he got a call from the U.S. Department of Defense.

Eric Herrera was recently listed on the Forbes 30 Under 30 List. Herrera discovered and optimized a bacteria from the arctic that he’s using to cultivate faster, safer and more sustainable extraction of critical metals from oil and gas. Herrera is pictured in the lab at MaverickX in San Antonio

James Lewis/Contributor

He began developing and testing antidotes for chemical weapons, eventually working as part of the lab that did the analysis to prove that Alexei Navalny was poisoned with the nerve agent Novichok. On a molecular level, Herrera said, it’s not too different from what he’s doing now.

Article continues below this ad

“All the chemistry I’ve done is pretty similar — whether it’s breaking down plastic or weapons of mass destruction or rocks,” he said.

While mining for critical minerals is necessary for technological advances like iPhones, electric vehicle batteries and renewable energy generation, it is paradoxically a practice that typically requires environmental harm.

READ MORE: Texas Republicans won’t say it, but climate change is on the special session agenda

Though critical metals are mined around the globe, most are refined in China, which globally dominates copper refinement. China is not naturally endowed with a higher concentration of metals but has refining capabilities that lead the country to import and refine metals, harnessing global power over them.

Article continues below this ad

“They were able to think 30 years ahead and actually have that refining capability to turn that rock into that ingots,” Herrera said. “We’re behind.”

In part, though, he said China has been able to develop such efficient metal-refining capabilities because of lax environmental regulations. For Herrera, who grew up on a ranch in Eagle Pass, respect for the environment must be integral to any business he runs.

Strategizing how to utilize the byproducts of MaverickX’s method is a part of that. When dissolving rock, after the wanted metals and minerals are taken out, there are waste streams of magnesium and calcium Herrera said have no value.

He said the company could deploy carbon capture by pumping carbon dioxide, removing the metals they want, and mixing what remains — calcium, carbon and oxygen — to make the calcium carbonate limestone.

Article continues below this ad

RELATED:From landfill to bus: Energy partnership turns biogas into fuel used by VIA

Everything in the MaverickX process is liquefied, he said, which is safer and easier to control. When pumping water out of oil wells, the producer cleans the water. While it is not cleaned enough for human consumption, he sees potential in using that wastewater for data centers that would otherwise draw down community sources of drinking water.

“There’s no way to get around harming nature,” Herrera said. “I think we need to do everything possible to sort of advance as much as possible in our metal extraction … but we have to do it responsibly.”

Article continues below this ad