CONCERT REVIEW:

Houston Symphony

October 17, 18, and 19(m), 2025

Jones Hall

Houston, Texas – USA

Houston Symphony, Christian Reif, conductor; Hélène Grimaud, piano.

Julia PERRY: A Short Piece for Orchestra (1952)

Kurt WEILL: Symphony No. 2 (1933-1934)

George GGERSHWIN: Piano Concerto in F (1925)

Lawrence wheeler | 20 OCT 2025

Friday evening, the Houston Symphony presented three diverse works from the first half of the 20th century. Spanning 27 years, all three works are loosely connected by jazz elements. The featured soloist in Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F was Hélène Grimaud. Making his Houston Symphony debut was conductor Christian Reif, chief conductor of the Gävle Symphony Orchestra in Sweden.

Conductor Christian Reif (christianreif.com)

In 2024, Reif and his wife, soprano Julia Bullock, won a Grammy Award for their recording Walking In the Dark. Since 2022, he has served as music director of the Lakes Area Music Festival in Minnesota. I was able to view two excellent live-stream performances– Humperdinck’s opera Hansel and Gretel and Wagner: The Ring Without Words. That high level of musicianship was brought to the Jones Hall stage tonight, making this an auspicious debut for Reif.

Julia Perry (1924–1979) faced the dual challenges of being a woman and an African American in the predominantly white and male world of classical music. Perry’s career unfolded amid the Civil Rights Movement, and her compositions reflected a commitment to both her craft and advocacy for racial and gender equity during a time of social upheaval and racial challenges in the mid-20th century.

A Short Piece for Orchestra is a testament to Julia Perry’s enduring impact on American classical music. In 1965, it became the first piece by a woman of color (and the third by a woman) to be performed by the New York Philharmonic. A dynamic and skillfully written work, Perry packs an 8-minute five-part form with rhythmically and dynamically contrasting subjects. Her use of serial technique gives the work a harmonic edge. Opening with fast-driving rhythmic figures that could have come from Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story, the piece morphs into lyrical woodwind solos. The first subject returns with different counterpoint figures, then settles into a slower Copland-esque section beginning with a meditative flute solo. The first subject returns a third time before an abrupt ending.

Reif’s cuing was accurate and precise, ensuring a well-coordinated performance of this “new” piece. He skillfully maintained forward motion without the music feeling rushed. Highlighted by numerous wind solos, the symphony musicians represented Perry well, inviting an exploration of her other works.

Kurt Weill’s best-known work is The Threepenny Opera (1928), written in collaboration with Bertolt Brecht. It contains Weill’s most famous song, “Mack the Knife.” Although successful, Weill’s working association with Brecht came to an end over politics in 1930. Even though Weill associated with socialism, Brecht tried to push their work even further in a left-wing direction. According to his wife, Lotte Lenya, Weill commented that he was unable to “set the Communist Manifesto to music.” Weill fled Nazi Germany in March 1933. A prominent and popular Jewish composer, Weill was officially denounced for his left-wing political views and sympathies, and became a target of the Nazi authorities, who criticized and interfered with performances of his later stage works.

The Second Symphony is Weill’s last purely orchestral work, and his orchestral masterpiece. It was written the same year as the music for Jacques Deval’s play Marie Galante, and begun concurrently with his better-known ballet, The Seven Deadly Sins (1933). Alternately called Symphonic Fantasy or Three Night Scenes, the symphony is based on classical forms with a highly personal style and use of harmony. Full appreciation is an acquired taste. It took four decades before the symphony regained attention after a lackluster premiere, and it is now considered a major work of the 20th century. Reif and the Houston Symphony gave the Jones Hall audience as fine a representation as one could have wanted, allowing for objective evaluation and appreciation.

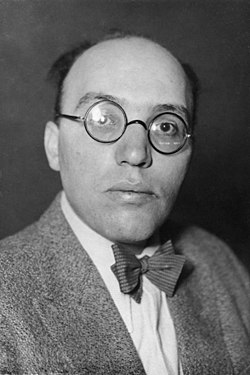

Kurt Weill in 1932. (Bundesarchiv)

After a dramatic and tense “Sostenuto” opening, we hear a trumpet solo with a dance-rhythm accompaniment evocative of cabaret music, suavely rendered by associate principal John Parker. A driven “Allegro molto” section has changing rhythmic figures under alternating wind solos. Dynamic punctuations and shifts of tempo keep the music off-balance, perhaps a reflection of Weill’s tenuous circumstances. Brilliant writing is followed by a curt ending. Reif again conducted with clear cues while indicating articulation and expression. His motions were so fluid and natural that it would be easy to forget the underlying complexities of the score.

The second movement, “Largo,” is funereal in character, complete with pulsing timpani beats. This gives way to a softer section in the same tempo. A solo cello plays a melody that, given a different harmonization, could have been written by Rachmaninoff. This was gorgeously played by principal cellist Brinton Smith. Immediately following is an operatic trombone solo, played with polished tone and legato phrasing by principal trombone Nick Platoff. The pattern of alternating lyrical melodies with dance-like accompaniments and the martial funeral music continues to the end of the movement. Reif captured the movement’s poignant mood without it becoming maudlin.

The third movement—“Allegro vivace”—begins with scurrying sixteenth notes and never looks back. It is a total romp, filled with satire, parody, sarcasm, and dark humor. Inherently theatrical, Weill makes references to Mahler, a German oompah band, and goose-stepping Nazi troops. The music speeds up by steps until it reaches a concluding tarantella. With the Houston Symphony musicians providing virtuosic playing, Reif maintained precise ensemble throughout. Such fun!

George Gershwin (1898-1937) wrote the Piano Concerto in F in 1925. He was challenged to write another piano piece that could equal his hugely successful Rhapsody in Blue, written a year earlier. In all respects, he did that and more. Like the Rhapsody, it blends classical and jazz idioms, but unlike the Rhapsody, it utilizes traditional classical form. While the former was orchestrated by Ferde Grofé, Gershwin did the Concerto himself. It is brilliant and colorful.

Hélène Grimaud has established herself not only as a virtuoso pianist but also as a committed wildlife conservationist, writer, and human rights activist. She is a member of the organization Musicians for Human Rights, a worldwide network of musicians and people working in the field of music to promote a culture of human rights and social change. This makes her appearance on the weekend of the “No Kings” demonstrations a timely coincidence.

Hélène Grimaud (helenegrimaud.com)

With 20 performances this season, Grimaud is establishing herself as a Gershwin Piano Concerto specialist. Being a world-class performer, she plays the notes exceptionally well, complete with a wide range of dynamics and articulation. Grimaud experiences synesthesia, where one physical sense adds to another—in her case, seeing music as color. The exploration of tone color may have been limited since the piano on stage tonight had a perfectly even sound through all registers and a glassy tone in the 7th octave. She remained firmly focused on Reif, with the exception of twice when she turned to smile at the audience. By following his baton, she was often just slightly ahead of the orchestra, which naturally plays slightly behind the beat. That sometimes made the music seem a bit pressed rather than “cool.” It is possible that, since Jones Hall has been renovated since her last appearance four years ago, the acoustics are different.

The Concerto begins with a four-note rhythmic motif in the timpani (which Leonardo Soto made sound melodic as well as rhythmic) and finely completed by percussion. The Charleston rhythm sets a jazzy mood, followed by a pentatonic theme in the bassoon and bass clarinet. After an extended orchestral introduction, the piano introduces an alluring melody—the second theme. The first movement weaves these components together, which Grimaud and the orchestra executed with elegance, power, and a jazzy feel.

The second movement opens with bent notes in the French horn, followed by a trio of clarinets playing a blues chord progression. A muted trumpet emerges with an even more sultry version of the first movement’s second theme. Principal trumpet Mark Hughes played the wide-ranging tune seductively. Accompanied by banjo-like strummed strings, the piano picks up the pace with a quicker second theme. Grimaud infused this with coyish charm, evolving into a confident strut. Guest concertmaster David Chan played a wonderfully idiomatic violin solo. Grimaud mused in a piano cadenza. Two flute solos were expressively played by principal flute Aralee Dorough.

The third movement is a fast-paced rondo with a toccata feel that sounds like New York. (Gershwin borrowed more than a few ideas from himself when he wrote An American In Paris a few years later.) A virtuoso showpiece for the piano, Grimaud kept on top of the beat with unrelenting kinetic energy. Reif was an excellent accompanist—always the true test of a conductor.

Grimaud’s playing of the Concerto was spectacular. She completely owns this piece, bringing technical brilliance and supercharged energy. The Houston Symphony musicians clearly enjoyed playing the familiar score, aided by stellar direction from Reif. Following a musically challenging first half, the audience was comforted by the work’s familiarity and accessibility, rewarding the performance with a standing ovation.

As an encore, Grimaud played Bagatelle No. 2 by Ukrainian composer Valentyn Silvestrov, one of a dozen she has recorded. Featuring a gentle bass riff and simple melody, the piece was a pastel watercolor painting following the multilayered oil painting texture of the Gershwin. Her exquisite timing and toning made the piece sound improvised.

Perhaps due to a selection of less familiar works—all 20th-century—the hall was not particularly full. It is essential for symphonies to search beyond the familiar warhorses when choosing programs. Concertgoers should also bravely go where they have not gone before and take a chance on the less familiar. Surprises and unexpected treasures await. ■

EXTERNAL LINKS:

About the author:

Lawrence Wheeler was a music professor for 44 years. He has served as principal viola with the Pittsburgh Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, and Houston Grand Opera Orchestra, and guest principal with the Dallas and Houston symphonies. He has given recitals in London, New York, Reykjavik, Mexico City and Houston, and performed with the Tokyo, Pro Arte and St. Lawrence string quartets and the Mirecourt Trio. His concert reviews have been published online on The Classical Review and Slipped Disc.

Read more by Lawrence Wheeler.

This entry was posted in Symphony & Opera and tagged Christian Reif, Hélène Grimaud, Houston Symphony on October 20, 2025 by Lawrence Wheeler.RECENT POSTS