Rhea Leen Linder says she’s not a fighter. But for the last several years, the 90-year-old has been locked in a legal battle to rectify what she deems an unfulfilled wish from the past: allowing her infamous aunt Bonnie Parker to rest alongside her lover Clyde Barrow.

The outlaw couple, who met in West Dallas, traversed the Depression-era Southwest in hijacked cars, robbing gas stations and stores, before dying in 1934 in a shootout with law enforcement.

Linder can recite with ease a poem in which Bonnie foreshadowed her fate: “Some day they’ll go down together,” she wrote. “And they’ll bury them side by side.”

Except they didn’t.

News Roundups

Today, Bonnie rests about 10 miles north of Clyde because her mother, Emma Parker, blamed him for her daughter’s death. “Look what he did to her,” Emma told a newspaper. “Now she’s mine. Nobody else has a right to her.”

Instead of interring Bonnie in the grave reserved next to Clyde’s, Emma buried her in a family plot.

Linder was raised by Emma, her grandmother, for a few years. She can understand how the specter of Bonnie’s death loomed over Emma during the two-year crime spree. Still, Bonnie’s poem stuck with Linder.

“If she was willing to give up her life for the man she loves,” Linder said, “she darn sure needs to be buried next to him.”

DeWayne Hughes, whose family owns and operates the cemetery where Bonnie is buried, disagrees.

And that’s why they’ve been in court.

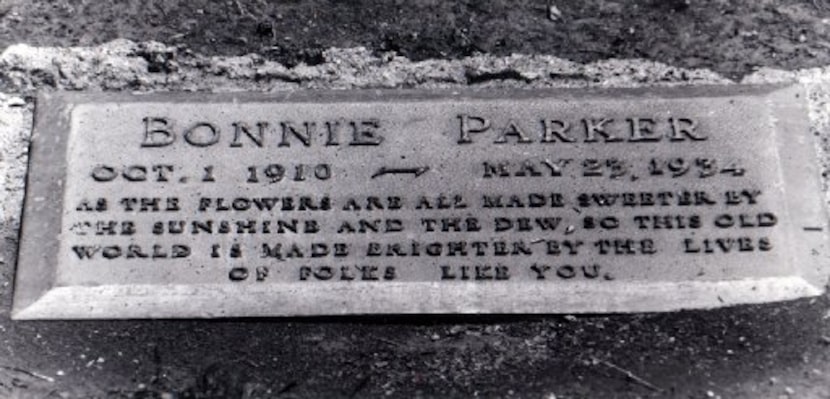

A photograph of Bonnie Parker’s grave marker was taken April 29, 1992, in Crown Hill Cemetery in northwest Dallas.

The Dallas Morning News

Public enemies, private lovers

Despite having been labeled as public enemies, Bonnie and Clyde captivated American society. Popular culture has romanticized their lives, even though they are believed to have killed at least 13 people. Hollywood fueled the intrigue with a 1967 movie in which Faye Dunaway portrays Bonnie as a chic, hedonistic femme fatale, while Warren Beatty’s Clyde is a handsome anti-hero, reticent but not unwilling to kill.

Rhea Leen Linder poses for a photograph during an It Came From Texas Film Festival screening of “Bonnie and Clyde” at the Plaza Theatre in Garland, Texas, on Sept. 12, 2025. Linder was invited to speak before the showing about her familial tie to Bonnie Parker.

Jason Janik / Special Contributor

Linder was born in October 1934, five months after Bonnie and Clyde were gunned down. The couple was seldom discussed among family as Linder grew up. She didn’t comprehend who Bonnie was, but her aunt made her a social pariah. “Kids would tell me they couldn’t play with me,” she said.

As a young adult, she’d catch wind of unbelievable tales around the couple’s misdeeds. But it wasn’t until after she retired in the 1990s that she delved into their story.

Around that time, she became close with Clyde’s sister Marie, who brought her into the world of historians, reenactors and fans devoted to the outlaw duo. Marie had wanted to see Bonnie’s remains moved into the plot next to Clyde’s, Linder said, but never took action.

Marie died in 1999 with her hope unrealized. After considering the idea further, Linder and a nephew of Clyde felt compelled to provide closure to the couple’s story.

Related

A protracted legal battle ensues

A protracted legal battle ensues

In 2018, Linder sought to provide that closure. She and her then-lawyer called Hughes, who oversees Crown Hill Memorial Park, the cemetery where Bonnie rests. When they asked him about removing a relative’s remains, Hughes seemed receptive, Linder said. But when Bonnie’s name was mentioned, there was silence. “You could have heard a pin drop,” she said.

When reached for comment on the call, Hughes said: “I’m not going to reply to anything that she said or might have said.”

Emails found in physical court records obtained by The Dallas Morning News show Linder’s lawyer, Bret Myers, asking Hughes for his cooperation in securing a disinterment permit for Bonnie over several months of 2018. Texas health code states such removal needs the written consent of the cemetery, the plot owner and the decedent’s relatives or next of kin.

Hughes and Myers were at odds over whether Linder met the statute’s requirements. According to Myers, Linder was Bonnie’s next of kin and the sole surviving heir of Billie Jean Parker, Bonnie’s sister, who originally purchased the grave. Thus, Myers wrote in several emails, Linder had inherited ownership of the plot.

Hughes, though, argued that the rights to Bonnie’s remains had been passed to the heirs of Billie Jean’s husband after his wife’s death. Billie Jean and her husband had no children, though he did have kids from a former relationship. No member of that family has emerged to oppose Linder’s request.

The legal parties had reached a stalemate. “I am asking one more time, will the cemetery agree to the disinterment permit?” Myers wrote in an email.

The cemetery did not. By December 2020, a new attorney for Linder had filed a dispute in a Dallas County justice of the peace court seeking the permit. The dispute was dismissed in February 2021 by a judge who ruled it did not fall under the jurisdiction of that court.

In 2022, Linder’s legal team made a new bid to remove Bonnie’s remains, this time filing a petition in a Dallas County civil court.

The case went to trial in June 2024. A judge then sided with Linder and ordered Crown Hill to remove Bonnie’s remains within 10 days.

The cemetery filed for a notice to appeal the ruling and an emergency motion to block the removal in July 2024. In August 2025, the Texas 5th Court of Appeals stayed enforcement of the lower court ruling in favor of Linder so that Crown Hill could appeal.

In a recent call, Hughes said his opposition to Linder’s request “has nothing to do with what I want or anybody else wanted,” adding, “It had to do with the determination of law.”

In a court document, Hughes offered another reason for his refusal. “Disturbing a final resting place for personal gain is profoundly disrespectful to the memory and dignity of the deceased,” he wrote in an affidavit from 2024. He did not specify what personal gain there would be.

‘This just needs to be done’

Linder turns 91 this month. She spends her days sipping coffee in her backyard with her rescue dogs, Sky and Bella, and cooking Southern cuisine — fried chicken, pork chops, baked beans — for her adult children, who live with her. She’d prefer to continue this quiet, “boring” life instead of having to worry about the court case.

While she doesn’t view herself as a fighter, she concedes, “I am hard-headed. This just needs to be done.”

But she knows in pursuing this, she’s going against the wishes of her grandmother Emma. “If she’s unhappy with me,” Linder says, “we’ll probably have a come-to-Jesus talk when we meet again.”

Infamous gangsters Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow pose for a photo in San Antonio.

Courtesy of Buddy Barrow