Tom Goynes still remembers the first time he dipped an oar in the San Marcos River. He’d grown up paddling in the bayous of Houston, where the water was murky and black and anything that fell in disappeared in an instant. On the San Marcos, the spring-fed water was clear as a windowpane and a consistent 72 degrees. “I put my paddle in, and I could see it,” he says.

It was 1967, and he was sixteen years old. His mother had paid the entrance fee for him to join his brother and another teen in the Texas Water Safari, billed as the “world’s toughest canoe race,” an annual multiday, 260-mile slog from San Marcos to the Gulf Coast. (Started in 1963, the annual event continues today.) The boys dropped out by the time they got to Luling, about forty miles in, with a fist-size hole in their boat that let in more water than Tom could send out with a bilge pump. He was hooked.

Tom started a canoe-rental outfitter with a friend in Houston after graduating high school, but the rivers of Central Texas kept calling to him. When he was 21, he sold his share of the business, packed up his girlfriend’s Ford Econoline van, and drove the two of them to Pecan Park, a campground he knew alongside the San Marcos, in a wide clearing just above a bend in the river that separates a long stretch of placid water from a series of rocky rapids.

“Right over there,” says Tom today, gesturing to one of the campsites scattered around the clearing. “We like this place.” Paula Goynes, now his wife, was 23 and starting to climb the career ladder as a data processor at Dow Chemical when she and Tom fell in love. The man who owned the campground back then let them live rent-free to manage it and run a canoe outfitter on the property, because it helped keep the campers coming back.

The couple bought another campground downstream, Shady Grove, and Tom established himself as a legend among river rats, racing the Water Safari dozens of times and winning it a total of nine. In 1990, the Goyneses seized an opportunity to buy the campground where they’d originally become enamored with the river. They named the property the San Marcos River Retreat, where they now have a home and host Boy and Girl Scout troops and church groups on the campgrounds. “Many times we’ll just marvel at it, like, ‘Wow, what happened?’ ” Paula says. “I can’t believe we’re here.”

It’s a late-summer Saturday morning as the Goyneses tell their story. Just beyond a row of trees, the river rounds the bend with a quiet burble. Sporting a yellow-gray beard, a thatch of shaggy hair, and a bandanna around his neck, Tom looks every bit the aging endurance athlete—until you notice his bone-thin legs, weakened by Kennedy’s disease, a rare degenerative neuromuscular disorder. The condition has also affected his speech and mostly confined him to a wheelchair. He often lets Paula finish his sentences. It’s on mornings like this that they come down the hill from their house and sit by the water, to take in the place that has defined their lives. Fly-fishers wade by first. Then comes the occasional couple in a canoe, or a solo kayaker slipping by almost silently.

Tom notices a lot in those reverent moments. A great blue heron’s wing tips skimming the water. A cottonmouth sunning itself on a rock. One year he spotted fountain darters, endangered fish so small that most people mistake them for minnows or don’t see them at all. About an inch long, with speckled backs and delicate fins, they darted in and out of the Texas wild rice leaves waving in the current. When he mentioned his sighting to a state biologist, the man was skeptical—fountain darters were thought to be confined to the Comal River. Still, Tom insisted. He’d seen them, more than once, and he even dragged himself into the shallow water with his arms to get a closer look. A few years later, researchers confirmed what he had been saying all along.

By late morning, the river begins to shift. A faint chorus drifts in first—tinny music from a Bluetooth speaker somewhere upstream—followed by the sweet, thick scent of sunscreen on the breeze. A candy-colored flotilla of inflatable tubes appears, and with it, the last of the morning’s subtlety slips away. The Goyneses know what’s coming.

Every summer, the San Marcos River swells with tubers.Photograph by Jeff Wilson

Every summer, the San Marcos River swells with tubers.Photograph by Jeff Wilson

In the early afternoon, about a two-mile drive west of the Goyneses’ property, a decommissioned yellow school bus sends a cloud of white dust rushing across a vast dirt field as it rumbles to a stop. The parking lot at Texas State Tubes, one of the two dominant tubing outfitters on this stretch of river, is a riot of color under a blazing sky. A couple thousand tubes in Day-Glo hues of pink, green, yellow, and blue form a mountain of vinyl bubbles—some of them displaying ads for a local beer brand or energy drinks—on one side of the dusty lot. Cars line up down Old Bastrop Road, waiting to get in.

Near the motorized air pump station, a group of women pile out of a red SUV with “Just Divorced!” painted across the back window and a Cash App handle scrawled underneath, alongside the words “Buy her a shot.” A couple of white pop-up tents serve as the Texas State Tubes check-in station, where bikini-clad women and shirtless men line up to sign liability waivers holding the company harmless from any incident.

Down a small hill to the riverbank, some tubers pass signs prohibiting glass and Styrofoam before they arrive at a bottleneck at the water’s edge, where they shove a cooler into the middle of a square float and tie their tubes together around it like the petals on a flower. Directly across the river, another crowd of tubers streams down the bank from Don’s Fish Camp, the other major outfitter. From here, the float will take two and a half to three and a half hours, a slow drift through cool water, after which one of the more than twenty buses in the Texas State Tubes fleet will pick everyone up and ferry them back to their cars. (Don’s works in reverse, shuttling tubers to the launch and offering parking at the takeout.)

The companies together send around five thousand revelers a day down the river during the tubing season, according to Ryan Abbott, the general manager of Texas State Tubes. Thirty-two, fit, mustached, and tanned to the point of leather, Abbott is dressed in a pale sun hoodie and flip-flops, the official waterman’s uniform. Taking refuge from the sun under one of the canopies, he explains he’s worked here for a decade, starting as a “tube boy” while studying at Texas State University, in in San Marcos, and watching the company’s daily clientele grow from a couple dozen people to as many as two thousand.

His boss, Texas State Tubes owner Richard Lawrence, started the company in 2012 along with a partner, after a lifetime spent on this stretch of water. “I was born in San Marcos—been swimming there my whole life,” Lawrence says. “My grandfather took me fishing, and I caught my first fish in the San Marcos River.” As a middle schooler, he worked for his uncle, who lived a few doors down from Don’s, which began operations in 2006. “We would always go for a dip after lunch on a long, hot day.” In college, he brought his buddies to float from a bridge on Old Bastrop all the way to his uncle’s place, and he knew instinctively that there was room for another outfitter in the market.

Back then, tubing was more of a free-for-all than it is today. Beer bongs, broken glass in the water, bass booming from speakers. “You’d have multiple fights per week,” Abbott remembers. Lawrence set up shop intending to create a slightly more buttoned-up option—better service, smaller lines—but what he did in the process was help blow up the size of the weekly party.

The demand was there. In roughly the same span of time Texas State Tubes has existed, the combined population of the San Antonio and Austin metro areas ballooned by nearly 1.5 million, a whopping 38 percent increase. The borders of Hays, Guadalupe, and Caldwell Counties—Caldwell and Hays are among the fastest-growing counties in the country—converge right where the tubing companies operate. Meanwhile, Texas State University continued its meteoric growth, approaching 45,000 students in 2025, a 75 percent increase from when it changed names from Southwest Texas State, back in 2003. What’s more, when severe heat and drought reduce the Lower Guadalupe River enough to make tubing nearly impossible there—which happened most recently in 2023—the San Marcos keeps rolling, fed by the Edwards Aquifer via the second-largest spring system in Texas.

Lawrence still floats with his old friends once a year and brings his kids to swim every month. Abbott, too, spends his summers on the water. “There’s only so much you can do when it’s a hundred and ten degrees outside,” he says. “It’s fun to go hiking, but it’s a lot better when you’re just sitting in seventy-degree water.”

The tubing operators share the Goyneses’ river culture, but from the opposite pole. The Water Safari that shaped Tom’s life is a kind of Texas ritual—born of reverence for the river’s power. Tubing is another Texas ritual, just as iconic in its own way, but it treats the river more as a playground. And it’s on the 1,800 feet of San Marcos riverfront that bounds the couple’s property, about a quarter of the way into the tubing route, that these rituals collide.

A truck full of cans and trash left behind on the river near the San Marcos River Retreat. Courtesy of Tom Goynes

A truck full of cans and trash left behind on the river near the San Marcos River Retreat. Courtesy of Tom Goynes  Trash from tubers on the Goyneses’ property. Courtesy of Tom Goynes

Trash from tubers on the Goyneses’ property. Courtesy of Tom Goynes

Beer cans everywhere,” Paula says as she calls up cellphone photos of hundreds of cans on the riverbank after a big tubing day. Underwater videos of cans lining the riverbed. Videos of people shotgunning beers on the gravel beach along her property. For the past dozen years, the thousands of tubers who float by all summer have become the scourge of the Goyneses’ lives.

For decades, Tom has been as much an advocate as a paddler. “He is Texas rivers,” says Mike McClabb, a former river guide, canoeing competitor, and frequent collaborator. “Tom has done more for the San Marcos River than anyone.” Tom helped establish the Texas Rivers Protection Association, a scrappy nonprofit, in the late eighties and served as its president for more than thirty years, weighing in on some of the most consequential water fights in the state. The TRPA pressed towns including Kerrville and San Marcos to adopt higher standards for their sewage-treatment plants, challenged water rights permits on the Guadalupe and Brazos, and raised more than $100,000 to secure paddlers’ access at Hidalgo Falls. The association also joined local campaigns to block a rock crusher on the Upper Guadalupe and preserve minimum stream flows on the Brazos and Guadalupe.

But over time, the focus of the Goyneses’ attention shifted to their own backyard. As the crowds grew over the years, the messes they left behind them grew accordingly. So did the tension between the two poles of river culture. First, the Boy Scout groups staying at the couple’s campground started having trouble with their canoe outings, either because they couldn’t make their way through the mass of tubes or because tubers were trying to give them beer, Tom says. Then it got worse. Tom says a male tuber raped a female tuber just past the tree line on their property in 2014, an incident he spoke about at an annual Texas Parks and Wildlife hearing two years later.

Around the same time, a parallel fight was playing out twenty miles down the road in New Braunfels. The city passed a “can ban” in 2011 that outlawed disposable containers and capped cooler sizes on the Comal and Guadalupe Rivers inside city limits. Trash volumes dropped, but the backlash was ferocious: a lawsuit from local beer distributors and tubing businesses, a “Can the Ban” rallying cry, and even dueling protest signs in the streets. In 2014 a judge struck down the ordinance as unconstitutional, only for an appeals court to reinstate it three years later; the Texas Supreme Court ultimately let it stand in 2018, making the can ban a permanent fact of life in New Braunfels.

In 2016, Tom and Paula, along with the TRPA, filed a nuisance lawsuit against Texas State Tubes and Don’s Fish Camp, arguing that the tubing operations had turned their stretch of river into a trash-strewn party zone. “We didn’t even want to ask for money,” Paula says. “We just wanted some rules like no glass, no Styrofoam, no beer bongs where you pour six beers in.” The case was resolved with a five-year agreement that required the companies to prohibit those items, as well as place a mesh trash bag on each tube, hire constables to patrol the route, and clean the river daily.

And it worked, to a point. David Karl Zambrano, the education and outreach coordinator for the nonprofit Eyes of the San Marcos River, which runs periodic cleanup efforts, says the difference is noticeable but incomplete. Volunteers working with his group haul out dozens of mesh bags each trip, mostly containing cans and plastic Jell-O shot cups. “But there’s a lot that doesn’t get recovered, because the current is constantly moving things downstream, and we’re only getting what hasn’t been pushed into the river bottom, where it’s not visible,” Zambrano says. “There’s a lot of spots where we only know to look because we put our feet down and realize that we’re stepping on cans.”

Tom and Paula Goynes host Scouts and church groups at their San Marcos River Retreat.Photograph by Jeff Wilson

Tom and Paula Goynes host Scouts and church groups at their San Marcos River Retreat.Photograph by Jeff Wilson

Part of the challenge, Zambrano and others point out, is jurisdictional. The most heavily trafficked stretch of the San Marcos drifts through an area that isn’t subject to any city ordinances. The river also crosses Hays, Caldwell, and Guadalupe Counties, further fracturing oversight. The town of Martindale, just downriver, passed its own disposable-container ban in 2018—led by McClabb, at Tom’s direction—and San Marcos followed suit with a citywide single-use-container ban in 2024. But between jurisdictions, cans are just fine, and enforcement of anything else is uneven at best.

That leaves the tubing companies to self-police, especially since their agreement with the Goyneses expired in 2021. “I don’t think we’ve had one fight on property all season,” says Texas State Tubes’ Abbott, referring to customers who sometimes get rowdy. At the end of every big tubing day, each of the companies sends kayakers down the river to look for stragglers and trash. Texas State Tubes also employs a monitor who sets up in a camp chair at the Goyneses’ gravel bar on weekends to make sure that particular spot remains comparatively orderly.

Meanwhile, a different kind of cleanup economy has also taken hold on the river: treasure hunting. Around midnight after a big tubing day, the river will light up as divers slowly make their way down the current, scanning the riverbed for iPhones, GoPro cameras, sunglasses, and so on. People will drop “easily a hundred iPhones per day on a weekend,” Paula says, and many of them can be salvaged for good money. Zambrano says the night divers call themselves “pirates.”

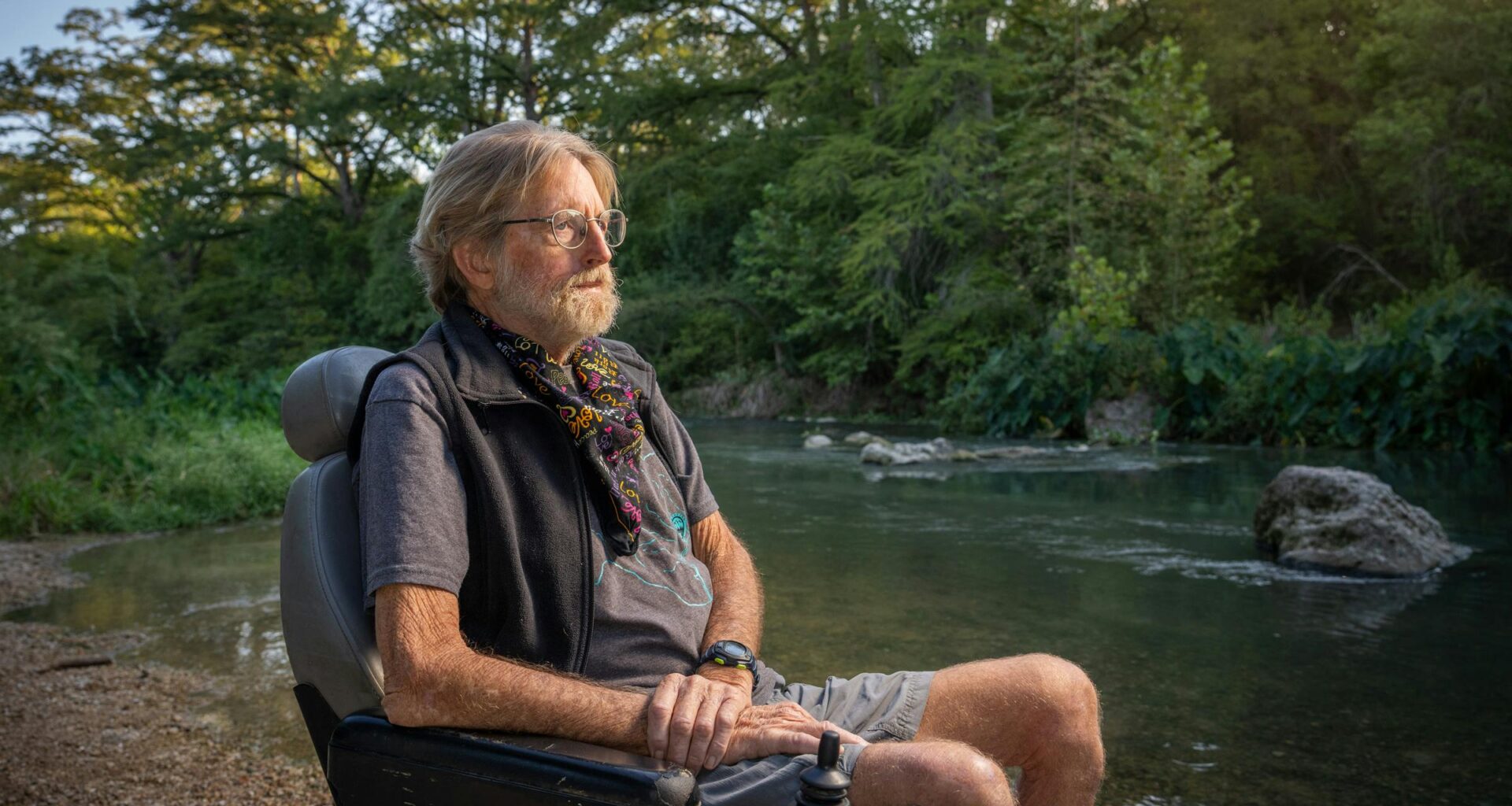

When the San Marcos is free of tubers, Tom Goynes is able to notice—and enjoy—the subtleties of nature.Photograph by Jeff Wilson

When the San Marcos is free of tubers, Tom Goynes is able to notice—and enjoy—the subtleties of nature.Photograph by Jeff Wilson

In June 2020, the State of Texas shut down the tubing operations ahead of the Fourth of July holiday because of COVID restrictions; the shuttle buses were deemed unsafe. Instead of drunken college kids washing up on the gravel bar, river otters began hanging out there. Deer showed up. Turkeys. One day, Tom says, he swears he saw a red wolf.

The Goyneses’ daughter, Sandy Yonley, who lives in Katy, stayed with the couple during that time. Having grown up on the property from the age of nine, she has San Marcos River water in her blood from all the days she spent swimming and splashing around. She paddled the Water Safari five times, the first when she was fourteen years old. That year, 1996, the Goyneses entered the race as a family in a 24-foot canoe, with Paula and Sandy up front and Tom in the back. They finished in 76 hours, but not before giving one another the nicknames Stumbles, Mumbles, and Grumbles: Stumbles for Tom, whose disease was already starting to affect his balance on portages; Mumbles and Grumbles for Paula and Sandy (they argued about who was which).

Sandy’s connection to the river eventually faded as career and family and adulthood took over. “She had given up on this river—didn’t want anything to do with it,” Tom says. But in the lull of 2020, after just a week there, “she fell in love with it again.” She watched her three kids experience the place with the kind of fresh wonder she’d had as a girl. Suddenly the one-story barndominium next to Tom and Paula’s house looked like prime real estate to her, and a routine roof-replacement project morphed into a complete reimagining of the structure as a three-story second home.

Signage at a river access point for the San Marcos River Retreat.Photograph by Jeff Wilson

Signage at a river access point for the San Marcos River Retreat.Photograph by Jeff Wilson

Then came 2021, and the party was on again. Although everyone agrees the tubing outfitters have stayed more or less true to the terms of the expired legal agreement, Tom turned his advocacy to an idea he’d first floated even before the lawsuit: reclassifying a chunk of the river as a kind of linear state park. From San Marcos to tiny Staples, about sixteen miles east, the river itself would fall under the jurisdiction of Texas Parks and Wildlife. Since the state already owns the surface water and the riverbed, as it does for every navigable stream in the state, Tom argues, establishing the park wouldn’t even require buying any land. Though there’s no other example of such a park in Texas, it’s not an entirely unprecedented idea. The Harpeth River in Tennessee, for instance, operates under a similar setup.

In Tom’s plan, the state wouldn’t have to add access points or campgrounds if it didn’t want to spend money. What it would have to do is enforce some Parks and Wildlife rules—especially the one that broadly prohibits alcohol in all Texas state parks. “All other state-owned land is G-rated,” he says. “You can’t play your boom box at full throttle and shotgun beer on the Capitol grounds. And that is as it should be.” The linear park might even be a moneymaker, he muses, as fines from violators and concession fees from outfitters would flow back to Parks and Wildlife to offset the cost of enforcement.

The idea has never gained traction, despite occasional flashes of hope. Back in 2014, Tom and Paula laid out the plan directly to the Parks and Wildlife commission at a public hearing. The following year, they made the pitch again and floated the idea of creating a task force, this time with a crowd of other concerned landowners and businesspeople from the area testifying in support of the idea. Six months later, Parks and Wildlife created the 38-member San Marcos River Task Force to study possible fixes and made Tom a member. At the first meeting, he brought up his linear-park idea again, and again it went nowhere.

Tom and Paula have long suspected that money, not logistics, has kept this proposal from catching on over the years. Tourism and recreation drive a lot of business in the area, and—for better or worse—a lot of that business comes in the form of alcohol sales. When New Braunfels instituted its can ban, the primary opposition came from a mix of local businesses—river outfitters, a hotel operator, and beer distributors—concerned about the effect on tourism and the local tax base.

Still, Tom says, there have been times when the park almost seemed possible. One neighboring landowner just across the river, the late “Babs” Baugh, once told him she would back the idea, “whatever it takes.” She was frustrated that she couldn’t enjoy the river anymore with her family. As a major philanthropist and the heir to a famous Texas fortune (her father was John Baugh, founder of the Sysco corporation), she might have had the kind of sway that could make something happen. She might have even donated the land for the park, Tom believes. Alas, she died in 2020; the Baugh ranch is now being developed as a residential community.

Kayaks for campers at the retreat. Photograph by Jeff Wilson

Kayaks for campers at the retreat. Photograph by Jeff Wilson  The retreat’s Cowboy Chapel. Photograph by Jeff Wilson

The retreat’s Cowboy Chapel. Photograph by Jeff Wilson

On Sunday mornings, Tom rolls his wheelchair down the ramp from his and Paula’s wooden home on stilts, past Sandy’s three-story barndominium, across a patch of gravel and grass, and into a converted shedlike structure with a wall of windows and reclaimed wood paneling inlaid with a cross. This is the San Marcos River Retreat’s Cowboy Chapel, where shorts and sandals are the official church clothes and where Tom delivers sermons to a smattering of friends and followers who make their way here weekly or watch videos he posts online.

Though he was raised Catholic, Tom felt a calling to evangelical Christianity as a young man. In 1988, when he and Paula sold their Shady Grove campground, he enrolled at Dallas Theological Seminary—and quickly found himself a fish out of water. Dallas was no place for a guy who barely wore shoes, and he didn’t even own a suit and tie, the required attire at school. He lasted one semester, and shortly after the Goyneses returned to their beloved San Marcos River, they were able to buy the campground they’d originally settled on, as if it were fated.

“I think this is my cause,” he says today, the thump of Turtlebox speakers on the river continuing its gradual ascent as the afternoon kicks into high gear. Behind him, the river is a rainbow mosaic of tubes, swimsuits, cowboy hats, and coolers. Morgan Wallen songs from one cluster of coeds bleed into Kendrick Lamar from the next. “I often ask God, ‘Why here?’ ” Tom says. Why would the most abused part of the river happen to be right in front of the property belonging to him, of all people? Why did God lead him away from the Shady Grove campground, where there is no tubing, and back to this place? “As a believer, that’s the confusing part,” he says. “God put us here. About that, to me, there is no question.”

He knows that his lawsuit against the two tubing companies was more effective to tame the crowds and improve the river than any task force or public testimony. He gestures toward the music: “I mean, this is nothing like it was.” At the same time, he knows he’ll likely never see his linear park and actually put the issue to rest. Tubing, after all, is as sacred a Texas tradition as barbecue or high school football. Floating with a frosty beverage isn’t going away, no matter how much the Goyneses might wish it would. But could it be that their role is not to win, but to serve as a counterweight? By remaining a persistent voice for environmental stewardship and a watchful eye over the party, they help sustain a fragile balance. Tom nods. “Salt of the earth,” he says. “We’re not supposed to make the meat less rotten, just kind of neutralize it.”

Of course, he won’t be here to play that role forever, as the indignity of his physical condition reminds him daily. “Life is so freaking short,” he says. And as the metastatic sprawl of new homes, strip malls, and data centers risks depleting the aquifer, the relatively steady flow of the San Marcos could one day run low enough to radically alter the balance of this place, whether the Goyneses are here or not. The river’s flow rate today is often less than half of what it was just a decade ago.

The Goyneses have been contacted by real estate speculators and know they could sell their property for millions. “We are not selling to a developer,” Paula says, her voice betraying a grit that Mike McClabb calls “frontier woman, tougher than nails.” But they needn’t worry about that. Sandy’s kids have fallen in love with the river and the campground, and the youngest, now eleven, roams the property like she owns it. “She keeps telling me, ‘Don’t worry, Grandma. I’m going to take care of it for you,’ ” Paula says.

The sun by mid-afternoon is relentless as it blasts the slurry of beer, pee, sunscreen, and sediment that flows by. If you dipped an oar in this water, it would be as invisible as in the blackwater bayous Tom grew up around. He pilots his wheelchair up the path, back toward the house. Despite the knobby tires he’s installed, the chair stops as he tries to barrel over a large rock in the way. For a precarious moment, it looks like he’s going to tip over backward, but Paula is there, a step away. She reaches out a calm hand to steady him, and he’s off again.

Read Next