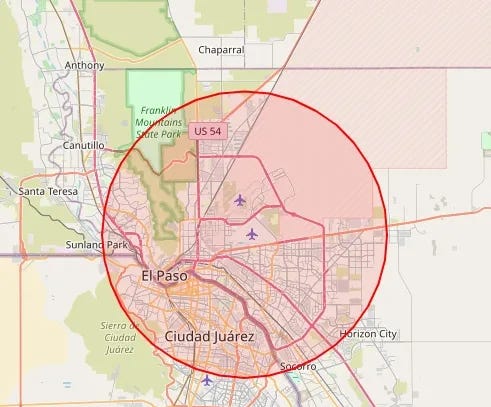

The area the FAA hastily declared as a ten-day “no fly” zone over El Paso this week, in response to what appears to have been a party balloon floating across the border from Mexico. The episode posed no immediate risk to people in El Paso or elsewhere but revealed profoundly dangerous attitudes.

The area the FAA hastily declared as a ten-day “no fly” zone over El Paso this week, in response to what appears to have been a party balloon floating across the border from Mexico. The episode posed no immediate risk to people in El Paso or elsewhere but revealed profoundly dangerous attitudes.

This post is a Q-and-A about the sudden closure of the El Paso airport two days ago.

Based on evidence available so far, it appears that a combination of arrogance, ignorance, and sheer incompetence lay behind a potentially major disruption in air travel, and potentially bigger problems in the future.

Here’s my sense of what we know now.

Two days ago, late on Tuesday evening, the FAA issued an emergency NOTAM, or Notice to Airmen, prohibiting all commercial and general-aviation flights to or from the El Paso airport, in far west Texas. The shutdown was originally announced to last ten days, until February 21. During that time no passenger, cargo, medical, or other flights would be allowed operate in or out of this city of nearly 700,000 people.

As detailed below, this was more drastic than most other emergency flight restrictions in most other cities, which have generally allowed airline and emergency aircraft to operate under close supervision from Air Traffic Control (ATC).

The reliable VASAviation site, using audio from LiveATC.net, captures the moment when a Southwest crew has just landed on Tuesday night, and learns that it won’t be able to leave the next day. The exchange occurs in the first minute of the clip below:

The El Paso tower controller asks the crew, which is taxiing toward the gate, if they’re planning to take off again quickly. The crew says No, on the contrary, they’re headed to the hotel for the night. The controller says, “just be advised” that quite soon the airport will be completely shut down—and will remain closed for the next ten days:

Pilot: “So the airport’s totally closed?” [A question he has never had to ask before.]

Tower: “Apparent-ly! We just got informed 30 minutes or an hour ago.” [Affable, with a “we’re all in this together” tone.]

Pilot: “So — for ten days, you guys are not open?” [Tone of: Let me be sure I’m hearing this right.]

Tower: “Well, we’ll be here [ATC controllers], but no air traffic!” [Jokingly].

Pilot: Laughs, at the absurdity of it all. Then “OK! Thanks for that heads up.”

The controllers in El Paso were taken by surprise. The Southwest crew was taken by surprise. The controller guessed that Southwest Airlines as a whole might also be taken by surprise, and she asks the pilot to pass word on to his company.

Sure. If you look at an aviation chart of the US, you’ll first be impressed by the sheer beauty of the topographic display. Here’s the big picture, from an FAA flight-planning map you would see in most flight schools around the country:

FAA flight-planning map. Most flight schools and FBOs (small-airport offices) have one of these on the wall, which pilots can use in planning and imagining flights. (FAA chart.)

FAA flight-planning map. Most flight schools and FBOs (small-airport offices) have one of these on the wall, which pilots can use in planning and imagining flights. (FAA chart.)

Then the closer you look, the more you’ll see the intricate patchwork of airspace designations, each with its own regulations, flight rules, restrictions, or cautions. For instance, here is a close-up of the area around Palm Beach. The red circles are “Temporary Flight Restrictions,” or TFRs, which accompany a president wherever he goes. One of these shown is centered on Mar-a-Lago, for the times Donald Trump is there. The other is centered on the Palm Beach airport, for when he is getting on or off a plane. And, again, notice the density of info shown on these charts, all of which pilots must understand.

Some of the airspace regulations involve the orderly flow of traffic into big airports. Some of them are warnings about military-training areas, with info on finding out whether they are currently “hot,” with artillery or aircraft fire. Some of them are strict no-go instructions, either permanent or temporary.

For instance, there is a permanent “prohibited” airspace zone over most of downtown Washington, from the Lincoln Memorial to the Capitol and Supreme Court. Not even airliners taking off or landing at DCA are allowed to fly in that space. There are similar permanent prohibitions over nuclear submarine bases, the homes of former presidents, and a few other places. The prohibited zone over Camp David gets bigger or smaller, depending on whether a sitting president is visiting there. For nearly 25 years, since the 9/11 attacks, much of greater DC has been under a very large “Special Flight Rules Area,” with strict limits on ingress, egress, and routing.

Then there are TFRs—Temporary Flight Restrictions. These can pop up for a variety of reasons. During wildfires or after hurricanes, TFRs can limit normal traffic, to clear the way for emergency crews. During big outdoor sporting events, from MLB games to the Super Bowl, TFRs keep aircraft from flying over crowds. During political campaigns, you can tell where the nominees and the president are headed, by following the rings of red TFR circles forecast for their campaign stops.

For people working toward a pilot certificate, knowledge about airspace is right up there with knowledge about weather, and learning how to take off and land. If you take everything a student driver needs to learn about road signs before getting a driver’s license, and multiply it by 1,000, that approximates what every pilot needs to learn about reading an airspace chart.

Here is a screen shot of the original NOTAM, or Notice to Airmen, which the FAA issued announcing the 10-day El Paso lockdown. This was different from anything I had seen before. It stood out in three ways.

Its suddenness. Safe flight involves planning—weather, airspace, fueling, maintenance, and so on. You want to think through the journey in your mind and on your charts, long before you take off.

Thus everything about the FAA is organized with planning in mind. Most “special” airspace has been there for a long time. (For instance, the specific altitudes and routes private planes can take around major hub airports.) When TFRs pop up, the authorities give you as much advance word as possible, usually several days ahead.

That was the first oddity about this measure. It was issued at “0332 Universal Time” (“Greenwich time”) on February 11. That means 8:32pm in El Paso on Tuesday night. And it was slated to go into effect just three hours later, at 11:30pm local time. Why did this short notice matter? Imagine an airliner or private plane on a four-hour flight to El Paso. It might have taken off with no sign of trouble, only to learn en route that it would not be allowed to land.

The only remotely comparable episode I can think of was the 9/11 mass grounding of planes, leading to aircraft and passengers stuck in place for a number of days. (As depicted in Come from Away.)

Its vagueness. TFRs are usually accompanied by an explanation of the reason. E.g. “the Super Bowl.” Or “VIP movement,” of a president or others. This one simply said “Special Security Reasons.” That is boilerplate language for some TFRs, but this one was unusual in the fast-changing public explanations of the reason behind it.

Its severity and duration. TFRs usually last for a few hours (for a sporting event or VIP arrival) or at most a few days (natural disasters, etc). This one was scheduled for ten days. Again, the only comparison would be after 9/11—and that, of course, was after a historic mass-casualty attack, rather than an undefined issue on the southern border.

The initial order also said that greater El Paso was “national defense airspace,” and that the military would use “deadly force” against offending aircraft if need be. All of this was unusual.

Not directly, or immediately. Planes inbound to El Paso would proceed safely and normally—unless they were scheduled to arrive after 11:30pm, in which case they would be routed elsewhere. Planes leaving from El Paso would take off before the deadline—or similarly miss the deadline, and have to stay on the ground.

The indirect safety hazards are a different story. At face value, the NOTAM would have forbidden all Medevac or other emergency flights. Would this have cost lives? Not just passenger flights but also cargo shipments and UPS/FedEx deliveries would be stalled. It’s easy to imagine the ripple effects of medicines, medical equipment, manufacturing supplies, perishable goods, and other items being delayed for more than a week. To say nothing of people planning trips for vacations, weddings, funerals, family visits, or other time-sensitive events.

This is why officials in El Paso were quick and passionate in their objections, and were relieved when the “ten-day” restriction was shortened to one day.

I care—as a long-time aviation practitioner, and as an even longer-time American—because the Administration’s handling of this event appears to have displayed its contempt for the two cardinal rules of aviation safety.