Bobby Pulido isn’t great at politics. At least, not yet. He understands issues well enough—he can speak passionately, knowledgeably, and extemporaneously about immigration, healthcare, and guns—but his speech lacks the smooth patter of an experienced campaigner. When he answers questions from a potential voter, he has a Biden-esque tendency to gear up like he’s about to blow the mind of the town hall attendee who asked it, sometimes starting a response with a condescending “Guess what?” He comes off like someone used to being the political buff in rooms full of musicians; that’s less likely to be the case when he’s taking a question from someone who has turned up at a town hall fourteen months before an election.

What Pulido does have right now is a famous name, especially in Texas’s Fifteenth Congressional District, which the musician-turned-Democratic-politician seeks to represent. Once a reliable Democratic stronghold in the Rio Grande Valley, the district elected Republican Congresswoman Monica De La Cruz, the first GOP official to hold the seat, in 2022, then went for Trump in 2024. The district extends from the border in South Texas all the way up to Gonzales, some four hours north.

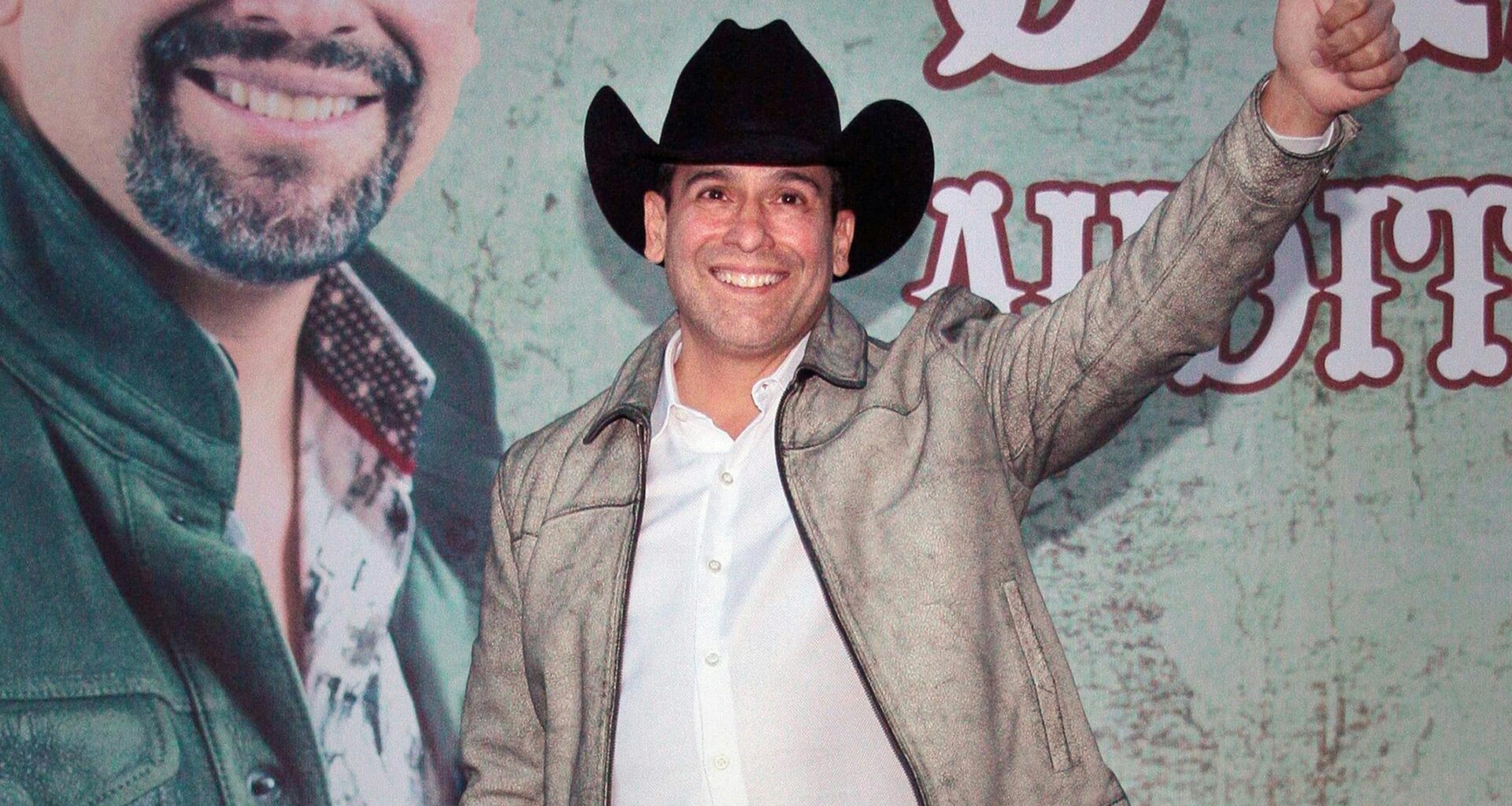

Pulido, the son of Tejano legend Roberto Pulido, grew up in Edinburg and began his own musical career in the nineties as a teen idol. He’s still winding down the final dates of a farewell tour that’s taken him to cities all over both sides of the border. He has a Latin Grammy and a stack of Tejano Music Awards; for his August farewell show in Mexico City, he headlined the iconic, 10,000-capacity Auditorio Nacional. But he was also a political science major during his stint at St. Mary’s University, and his interest in politics was sincere, especially as he found himself disagreeing with national Democrats on issues like immigration.

“I believe I know what it takes to win, and it’s not what they’ve been doing,” Pulido said over a smoothie at CoffeeZone Bistro in Edinburg. For years, he considered a career shift, but it didn’t become real for him until 2022. That November, he was invited to spend election day with Congressman Vicente Gonzalez, who’d represented the Fifteenth since 2017 and had just jumped districts to the Thirty-Fourth, after the first redistricting of the decade tilted it to favor De La Cruz, whom Gonzalez narrowly defeated in 2020. “I was like a kid in a candy store asking him a bunch of questions about different politicians and policies. I was very curious about the whole thing, and his wife, Lorena, asked me, ‘Have you ever considered running?’” That, Pulido said, was his dream—but he had a good life as a musician. Still, he went home and relayed the conversation to his wife, Mariana.

“She said, ‘You’d be great at that, but would you really want to?’ And I said, ‘I’ve always wanted to, but I never was arrogant enough to feel like I was the guy for that,’” Pulido recalled. “And she said, ‘Well, I haven’t seen you write a song in a while.’”

Pulido announced his candidacy on September 17 with a bare-bones team. His campaign manager, Abel Prado, previously worked for South Texas Democrats including Congressman Henry Cuellar and state Senator Eddie Lucio Jr. but is running his first campaign. When Pulido held its first official event at the Cielito Lindo dance hall in Mathis, he forgot to pass out yard signs until attendees noticed them stacked in the corner of the room.

That Pulido launched his campaign in a small town two hours north of the Valley helped signal what type of campaign he would be running. Mathis isn’t a part of the district that suddenly flipped from blue to red; it’s been reliably conservative since 2011. Voters in San Patricio County cast ballots for Donald Trump by a roughly two-to-one margin in the last three Presidential elections, and Mitt Romney and John McCain won the majority before that. Prado told me it was a natural place for the race to start, because for Pulido to win, he’ll need to not only pull big numbers in his home community in the Valley but also convince some GOP voters in the beet-red northern part of the district that he’s their kind of guy. Luckily for the candidate, Latino voters who cast ballots for Republicans listen to Tejano music, too.

“The name Pulido is very well known,” Patricia Avila, executive director of the Texas Conjunto Music Hall of Fame & Museum in San Benito, explained. “A lot of people grew up listening to Bobby Pulido’s music and especially his dad’s music. His family has been in the music business for over sixty years.”

Pulido doesn’t think the familiarity many voters have with him because of his music career will automatically win them over, but he believes it might persuade them to give him a shot. It’s a model that’s been successful for Republicans in Democratic strongholds—Sonny Bono, Clint Eastwood, and Arnold Schwarzenegger all won elections in California—but hasn’t been tested much by Democrats in red states. “It opens the door, but you don’t get in the house,” he explained. “What’s happened a lot of times to people in my party when they run, they don’t even get the door open. But it’s still not a guarantee.” Pulido cites Trump’s ability to connect with voters as an unlikely inspiration. “I give Trump credit—he has star power, but the guy’s a hard worker, man. If he had just gone ‘Vote for me, I’m famous,’ I don’t think he [would have won].”

Pulido believes his experience performing lends itself to campaigning. “In music, you look for a connection. You’re reading people. You don’t get to know them, but you know them. You look in the crowd and you can kind of get an idea of that person,” he says. “It’s definitely very similar to campaigning.” It’s also different, though—in campaigning, the goal is persuasion, while in performing, the goal is delivering to a crowd that has already bought in. It’s not clear yet if Pulido can pivot from the former to the latter.

When it comes to policy, Pulido’s a Democrat in the Blue Dog tradition. “They’ve painted a narrative of what a Democrat is. It’s not who I am,” he says. “‘No, I am not an atheist. I love God. I’m a Catholic. I’m not pushing to turn their kids trans.” He likes talking about his collection of guns, his love of hunting, and the importance of the oil and gas industry to the district. When asked about abortion at the town hall in Mathis, he described Texas’s ban on the procedure as “draconian;” but he also described himself as pro-life and stressed personal responsibility, explaining that if his own teenage son got someone pregnant, he’d urge him to “man up” and take care of the baby.

On immigration, in particular, Pulido is seeking to distinguish himself from previous Democratic campaigns. He praises the immigration deal, proposed by Republican U.S. Senator James Lankford, that would have restricted the entry of asylum seekers but also increased the number of green cards issued each year; he laments that Trump pushed conservatives to kill it. He’d like to see the U.S. establish vetting locations in Central America to make the asylum process more efficient and careful. He believes that the border is the primary issue that cost Democrats the Valley.

“I think there was this assumption in the Biden administration that if you were tough on immigration, Latinos would go against you, which is a bunch of bulls—t. That’s insulting to Latinos,” he says. His frustration with the Biden administration’s immigration policy—and specifically, that it took the former president two years to visit the border—is palpable. “I think that they did it out of an abundance of caution, not to piss off Latinos. But they didn’t realize that that was actually pissing off Latinos.”

Pulido isn’t the only Democrat to enter the race. Ada Cuellar, a doctor who is currently finishing a law degree (no relation to Henry), has also announced, running on a similar platform. As a doctor, she leads her pitch with health care and reversing recent GOP cuts to Medicaid and Obamacare. She knew Pulido was contemplating a bid—the rumor had been circulating for more than a year, and a barbecue joint north of the Valley had a sign reading “Run, Bobby, Run” out front well before he announced his candidacy—but with a push from 3.14 Action, a political action committee that recruits candidates from STEM fields, she decided to make a bid anyway. “I don’t know that his crowds are necessarily going to translate into votes,” she told me, “because even if you look at his [social media] pages, a lot of the people who comment are outside of the district or from Mexico. He’s a lot bigger in Mexico, really, than in South Texas at this point.””

Cuellar isn’t wrong that Pulido’s celebrity status might muddy the waters when it comes to what’s actually drawing people to his events. After about an hour of speaking to the crowd in Mathis, which included folks who’d traveled in from Bexar County, well outside the district, he wrapped the town hall and invited the musical guest who opened the show, fellow Valley Tejano star Lucky Joe Eguia, back out onto the floor. Pulido told the crowd he had a song he wanted to sing for them. Eighty people rushed the stage like it was what they had been waiting for the whole time.

Read Next