Thomas Jefferson Elementary School, nestled in the Timbergrove neighborhood of Houston, just north of downtown, enrolls some 340 students — 96% of whom are low-income and roughly a third of whom are just learning to speak English.

Since the pandemic, student achievement has been hard to come by, hitting rock bottom during the 2020-21 school year, when 77% of students were below grade level in reading and 86% in math. And while scores rebounded some over the years, they were low enough during the 2023-24 school year to earn the campus a “D” rating on the state’s accountability system.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

That same year, the state took over operations of the Houston Independent School District, appointing a new hard-charging and controversial superintendent, Mike Miles, who, among many other things, has overseen the replacement of dozens of principals and put a premium on educators who deliver results.

“We work really hard to make sure that we hire the correct people for the job,” said Jefferson Elementary Principal Claudia Florez, who Miles hired for that role the same year. “Teaching is not for everyone.”

“We make sure that people truly understand what it is that they’re getting themselves into,” she added. “When I meet with my teachers, I’m very clear with the expectations I have for them.”

Houston Trumpets ‘Historic’ Gains from Schools Takeover, But Doubters Remain

In return, Florez promises to support her educators with the resources, planning time and professional development required to meet the needs of every child that walks through the front door. That’s why she wasn’t surprised when the Texas Education Agency released district and school ratings in August for the 2024-25 school year and saw that Jefferson had turned its “D” rating into an “A.”

As it turned out, Jefferson was just one of 20 schools in Houston that made that leap, signaling something even bigger may be afoot. In fact, Houston ISD went from having 121 “D” and “F” rated schools in 2022-23 to having 18 “D” schools last year and none rated as failing — meaning three-quarters of the district’s schools are now rated “A” or “B.” Fifty schools earned a “C” rating.

The results whisper of a new trajectory for achievement. Houston ISD — the 176,000-student school district where 90% are students of color, 78% are low-income and nearly 40% are learning English — earned a “B” in the state’s much anticipated accountability rating system, up from a “C” last year.

Yet as is often the case, the back-slapping and glad-handing that typically follows a sudden catapult in academic achievement, especially on the heels of a state takeover, has been undercut in equal measure by critics who say the improvements are too good to be true. They say the changes come at a steep price to the community and question their staying power.

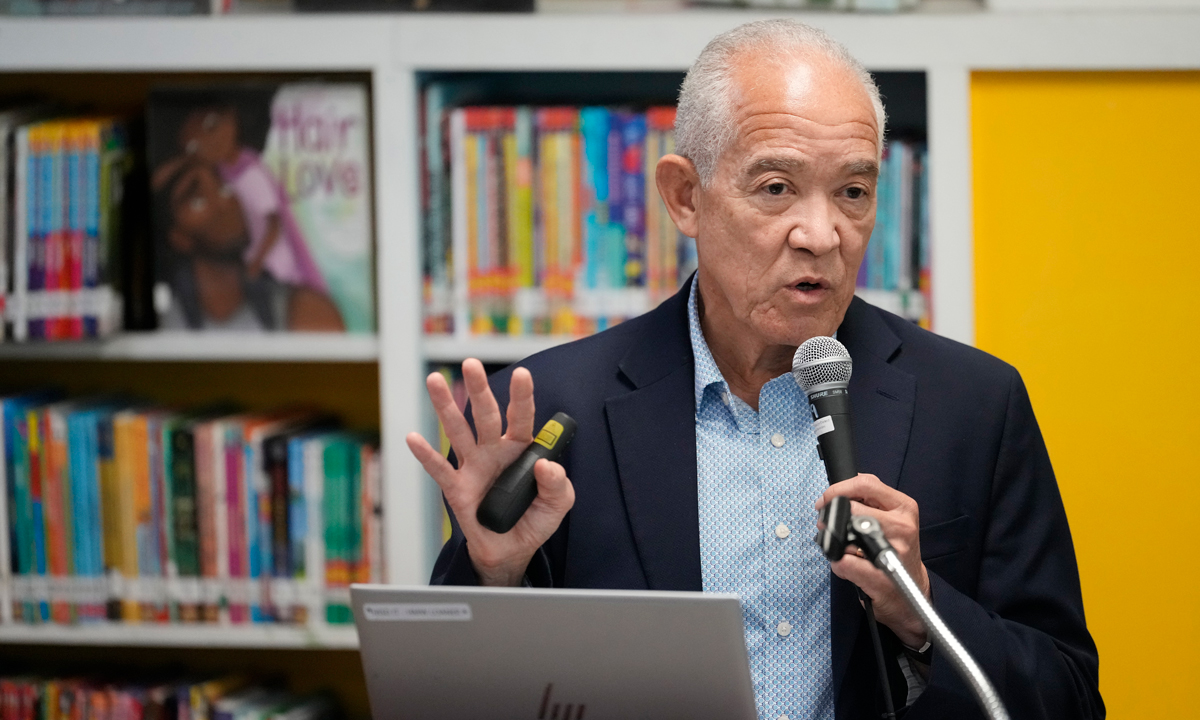

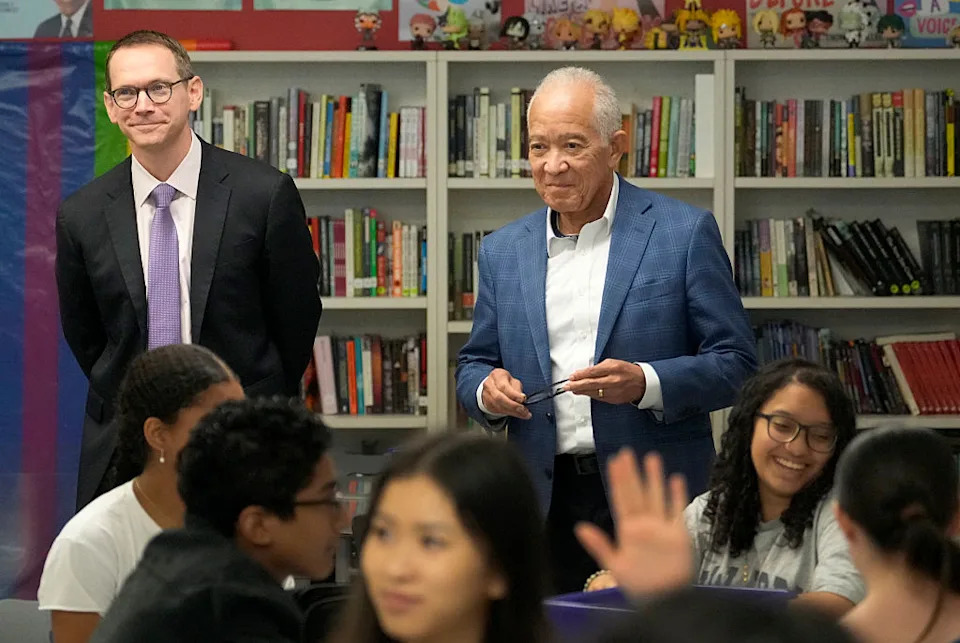

Texas Education Agency Commissioner Mike Morath (l) and Houston Superintendant Mike Miles. Morath hired Miles to lead a state takeover of the district. (Melissa Phillip/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images)

After the release of the ratings, Texas Education Agency Commissioner Mike Morath and Houston ISD Superintendent Mike Miles touted the findings as evidence that the state takeover is working. And what better place to announce such progress than Jefferson Elementary itself.

“These historic outcomes are the result of wholesale systemic reform,” said Miles. “Two years ago, it was hard to believe that this could happen.”

Ending a Years-Long Standoff, State Officials Announce Houston Schools Takeover

“It doesn’t happen normally,” he added. “It would be hard for someone who isn’t steeped in data … to understand or believe that the transformation is getting these results.”

To be sure, state takeovers are inherently controversial no matter where in the country they occur — often garnering criticism from parents, teachers and local community members concerned that state-appointed district and school leaders are quick to implement drastic policy changes at the expense of local families. Many residents feel these top-down reforms aimed at improvement happen to them rather than alongside them.

In Houston, the reception was no different. But the takeover of Texas’ largest district — and one of the largest in the U.S. — has garnered outsized attention due to its scale. The Texas Education Agency announced last week the takeover of Fort Worth ISD, the second-largest takeover in Texas history, as just 34 percent of students across all grades and subjects are performing at grade-level on state exams and 20 campuses have been labeled “academically unacceptable” multiple years in a row.

As part of the Houston takeover, Miles targeted roughly one-third of its schools for wholesale reform rather than incremental changes sometimes seen in other state takeovers. In doing so, he prioritized funding to boost the quality of instruction and school building leadership, including having the most effective teachers instruct the lowest-performing kids; boosting teacher professional development; elevating the role of principals to coach teachers; hiring instructional executive directors to train principals; and attempting to institute performance pay.

But at the Houston City Council’s economic development committee meeting in September, Miles was booed by parents in the crowd and grilled by council members about teacher turnover, principal displacement and a drop in enrollment. Fanning the flames of discontent, Miles had recently secured a $173,660 bonus — news that came on the heels of an $82,000 annual raise included in a new five-year contract that increases his annual base salary to $462,000.

Study Finds Wide Range of Outcomes from State Takeovers

Miles pushed back on the accusations, calling them “conspiracy theories,” and asking naysayers to examine the data.

“We do a disservice to teachers and kids when you hear the nonsense. It’s a disservice when there is a lack of professionalism and poo-pooing the results of teachers who work really hard.”

But the data that Miles is asking his critics to focus on also raises some questions, said Rachel White, professor of education leadership and policy at the University of Texas, Austin, and founder of The Superintendent Lab, a hub for data and research on school district leadership.

Among them, between 2022-23 and 2024-25 the district experienced a 17% increase in the number of students identified as having a disability, but the number of state alternative assessments taken by Houston ISD students increased by 39% — more than double. Meaning, essentially, that there was a greater increase in students taking the alternative assessment than students who would qualify for that assessment. White noted that “these may be appropriate educational decisions — particularly since one reason for Houston ISD’s takeover was special education program-related failures. Nonetheless, it is important to keep an eye on shifts in who is taking assessments, and which assessments.”

Moreover, the number of beginning teachers increased from 7% to 12% over the last three years — an unusually large shift for such a short time span, and a trend opposite that of the state, which saw a decline in beginner teachers from 10% to 7% — while the proportion of veteran teachers also sank.

Contacted by The 74, district officials in Houston declined to comment on questions surrounding the data.

“This is not unique to Texas,” White said. “Accountability systems tell us some things, but they don’t tell us everything. And, while this absolutely may not be the case here, we’ve seen in prior research, accountability systems can be gamed. There are ways to shift things in order to get exactly what the accountability system wants.”

Indeed, perhaps just as controversial as that state takeover is the state’s accountability rating system itself, which has been delayed twice by lawsuits filed by dozens of districts accusing the state education agency of using retroactive and shifting standards, overemphasizing standardized testing, treating districts with high poverty rates unfairly, and lacking transparency in its scoring methods.

Jackie Andersen, president of the Houston Federation of Teachers, calls the new achievement data “bogus,” an accusation Superintendent Mike Miles dismisses as “nonsense” and “conspiracy theories.” (Yi-Chin Lee/Houston Chronicle/Getty Images)

“We don’t trust the validity of the scoring,” said Jackie Andersen, president of the Houston Federation of Teachers. “We’re comparing apples to oranges in terms of the tests that were administered and are being compared to one another. It’s data manipulation, plain and simple. He’s saying, ‘Everything is good, the scores are up!’ But we’re not looking at the same students, we’re not looking at the same tests, we’re not even looking at the same criteria for passing year to year.” Her criticism was echoed by the editorial board of the Houston Chronicle.

“The whole thing is bogus,” she added. “In any other administration, if a school had gone from an F rating to an A rating, they would have been investigated. And probably the principal and everybody in the school would have been terminated because that’s impossible. Come on now. Something is not right.”

In the case of Jefferson Elementary, for example, it received an “A” rating overall despite receiving a “C” on student achievement, or a 77 out of 100 based on whether students are meeting expectations on the state assessment. In fact, just 59% of students at Jefferson are at grade-level in reading and 51% in math. That’s hardly an “A,” but the overall rating is reflective of the progress made. And during the 2023-24 school year, Jefferson earned an “F” in student achievement.

One item that could mitigate the case against the doubters is that Houston has shown gains on other tests, including the National Assessment of Educational Progress and NWEA MAP Growth. The district can also point to the fact that chronic absenteeism dropped seven percentage points from the previous academic year, to 20%. And perhaps most importantly, improvements are especially concentrated in historically underserved areas that enroll primarily Black and Hispanic students from low-income families.

“We want Houston to be successful, because every one of these kids deserves a great education and one that’s going to prepare them for life,” White said. “…But we also have to be thinking about the broader system, and not just this short-term potential increase in accountability ratings. What does this look like in the long-term for the district in terms of stability of its principals and its teachers, as well as students’ love for learning and desire to continue to learn after they don’t have to do it just to get a good grade on a test?”

Looking ahead, the terms of the takeover are set to continue at least two more years, the Texas Education Agency announced over the summer. Miles said that it’s a necessary move to ensure the longevity of improvements made and reduce the risk of the district reverting to past practices after the state hands over leadership to an elected board.

Next up on the docket for Miles: Cementing a policy priority even more controversial than school ratings, he wants to link teacher compensation to effectiveness, launching the “largest pay-for-performance plan in the nation.”