The quickest way to learn firsthand about the history of a place — a city or region — is through its cemeteries. Walk among the gravesites, and you’ll see a story of a community etched in stone.

The pioneers who built it with their hands and fortunes and their sons and daughters, many of whom became the soldiers who defended it. Those families whose names now belong to streets and schools.

The faces, many of them unknown except to their family and friends, who gave the place character.

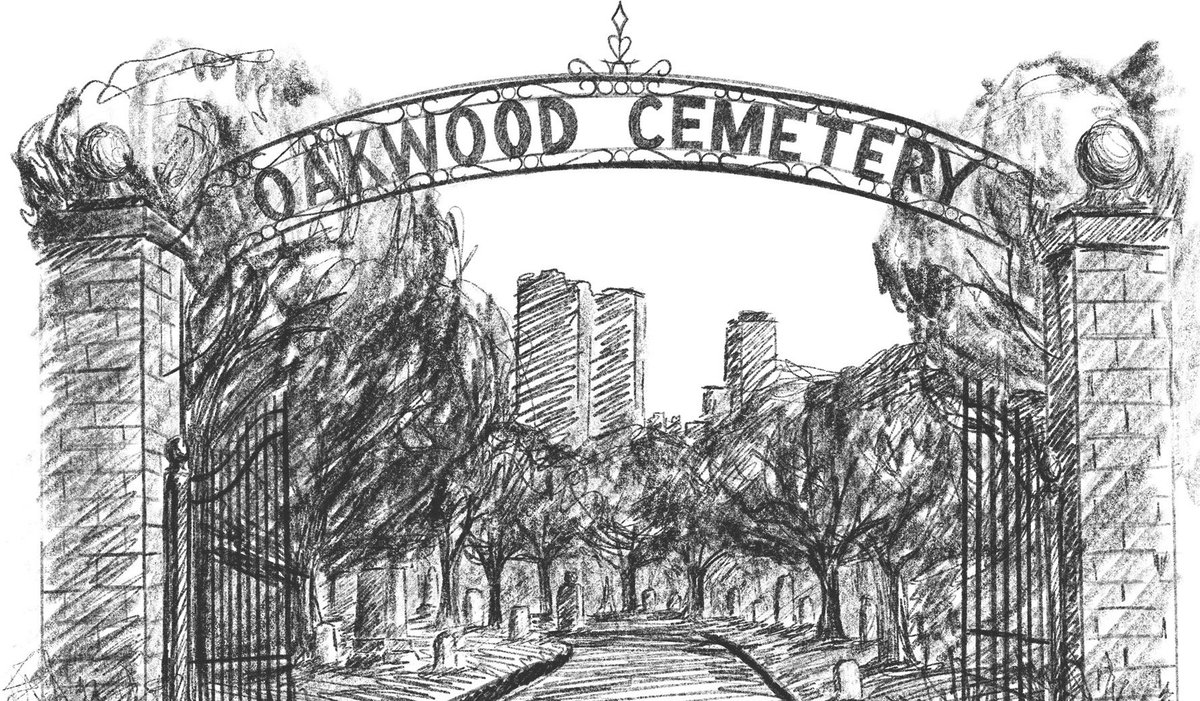

Oakwood Cemetery on the city’s North Side has always been a place of reprieve. Here is the final resting place for some of Fort Worth’s most notable, including Burk Burnett, K.M. Van Zandt, Luke Short and nemesis Jim Courtright, and Major Horace Carswell. R.L. Paschal is here, as are some Monnigs. Euday Louis Bowman, the hard-luck composer of the famed “Twelfth Street Rag,” has a nice place at Oakwood.

And whenever I visit, like this visit, I make my way to the “Henry” plot. It’s the final resting place for my great-grandparents, two of their daughters — my great-aunts, both unmarried — and a grandson, one of those infants lost before life began.

I’m standing at the gravesite, located just inside the arch that welcomes visitors like myself to this section of the cemetery. It carries the inscription “Calvary.” A cardinal sits atop it. The top two markers carry the inscriptions for the patriarch and matriarch with dates of death of 1920 and 1947.

Down and to the left lies the grandson. To his right should be the two markers of my great aunts, but both are covered with overgrown grass. I begin to kick at the grass until gray granite begins to appear.

“I really wish someone would come out here and clean that up,” I hear a voice say from the direction to my left. It startles me more than a little, my having been caught up in my own world.

“What was that?” I say as I turn to look toward the voice.

“I really wish someone would come out here and clean that up,” says a man I clearly recognize from a picture I have in the house.

That’s my great-grandfather!

“Do you work here?” he asks me.

“N-n-n-n-n-no,” I stammer. “Hey … uh, pardon me … what is your name?”

“I’m Alex Henry.”

I take a deep breath, trying to gather my wits. What in the hell is going on here? I blink hard, half-expecting the image to vanish, but he’s still there, as real as the headstone at my feet.

This is either the strangest day of my life or the beginning of a very long conversation with the dead.

I flinch at the sight of a coyote about 100 yards in front of me. That’s not something else you see every day.

“That’s just Wiley,” Alex says. “He roams the property for squirrels at lunchtime.”

“Wiley?” I say. “Like Wile E.? Wile E. Coyote?”

“What?” He looks at me, blank. No flicker of recognition. No smirk of shared Saturday mornings watching cartoons on a television that, to him, would be something out of science fiction.

“Well, I’m John Henry. Like you. I’m one of yours. I’m your great-grandson.”

“The hell you say! I’ll be damned. Who’s your daddy?”

He also probably wouldn’t recognize the humor in that phrase. He didn’t know my dad either, but I tell him. He knows my grandfather — his son — of course.

“Holy cow. This is deep. You come here often?”

He thinks this is deep, I say to myself. Generally, once a year, I tell him.

“I’ll be honest with you,” I continue. “Wiley isn’t the one who is scaring the bejesus out of me. How is it that you’re here right now?”

Alex tells me that when a person dies, the soul lifts free from the body but can hover. It can feel the gravity of the flesh pulling at it. That pull never fully releases. Even a century later — centuries later, he says — the spirit may return, drawn to the remnants of the body.

It’s never allowed to rejoin.

“So why do you appear in almost perfect form?” I say. “You don’t look like a ghost.”

The spirit retains a perfect memory of its physical self, he says. What I see is not the body returned, but the soul projecting how it remembers itself — face, posture, even clothing from the moment it last felt most alive.

“To the living, this appears as a ‘full body form,’” he says, “though in truth, it’s a luminous imitation, not flesh.

“I can come and go as I please,” he says. “I love my afterlife home, but it can get kind of boring.

“It’s never boring down here.”

And with that we begin to walk. He’s leading the way. I follow along, my fear having subsided, and my curiosity turned up to full blast.

We’re walking among droves of grave markers, almost all of them first laid more than a century ago. Those stones are reminders, Alex tells me, that a real person left their own mark on the world.

“All of them have a story to tell,” he says. “All of those stories are worth listening to. Keep it down. Don’t rustle up that son of a bitch.”

He points in a direction to our right.

“There’s a fellow buried over there who was as notorious as they come. Jim Miller was his name, though most folks called him ‘Deacon Jim’ in his day. Don’t let that church-going nickname fool you,” he says before continuing.

By the time an angry mob strung him up in Ada, Oklahoma, in 1909, he had the blood of dozens of men on his hands. Some say it all started right back here in Texas, near Gatesville, when he was accused of killing his brother-in-law. That was the first time he was accused, but it sure wouldn’t be the last.

Jim eventually became a hitman, all the while carrying himself as a gentleman preacher. He didn’t drink or cuss, and went to church regularly, and he always wore fine clothes too, including a diamond ring on his finger, stick pin on his coat, and that long black frock coat even in the blazing Texas heat.

“It was hot here then, too,” Alex says.

Fort Worth was where he lived, but his work took him across the Southwest.

Jim killed upwards of 50 people, they say, and got away with every one of them — mostly because witnesses wound up dead — until Ada, where he killed a rancher and former U.S. marshal.

Jim was arrested, but the townsfolk weren’t waiting on due process. A mob of about 200 stormed the jail and dragged Jim and three other men to a stable.

Alex continues: “As the noose was going over his head, Jim asked for two things — that his diamond ring be sent to his wife and that he be allowed to wear his black hat, which, as gentlemen, they permitted. Then he straightened himself up, looked out at the mob, and said, ‘Let ‘er rip.’”

That was that. Jim Miller was returned to Fort Worth for proper burial.

To our left as we walk up the road is a section for soldiers of the Confederacy. A memorial pays homage to their service. Edgy, I think.

Another voice suddenly breaks in.

“Folks think Texas marched in lockstep to secession, but here in Tarrant County the difference was just 28 ballots out of more than 700,” the man says to me. “It was neighbor against neighbor, and the tally could have tipped the other way with a handful of men changing their minds.”

It’s John Peter Friggin Smith, I say out loud to no one in particular.

“Call me Peter,” he says.

The “Father of Fort Worth,” Peter Smith served three terms as mayor and oversaw the organization of the city’s public schools, remaining one of their strongest advocates.

He went to Franklin College in Indiana and then entered Bethany College in West Virginia. The same year he graduated with honors, he moved to Fort Worth. The move to Texas was transformational for both.

“Fort Worth was little more than an abandoned fort at that time when I got here in the early 1850s,” he says to me. Peter says he taught in the town’s first school, established in an old hospital.

That school was the foundation for AddRan Christian University. Addison Clark got his first classroom experience there under Peter.

“I wonder whatever happened to AddRan,” Peter asks to no one in particular.

“It’s TCU! It’s in Fort Worth,” I answer.

Alex appears not to hear me. He was alive when TCU moved to Fort Worth in 1910. Peter simply ignored me. He died in 1901 in St. Louis on a trip to bring commerce to Fort Worth. By then he was the largest landowner in Fort Worth. Some of that he donated for this very cemetery, Peter says before getting back to the topic: secession.

“I did my damnedest to stop it. I was with Sam Houston and Throckmorton and, here, Middleton Tate Johnson in opposing raising a new flag.”

Tarrant County was pretty equally divided, likely because of Peter Smith’s opposition to leaving. Once it was decided, however, Peter went off to fight for the Confederacy.

After the war, Peter returned home to practice law and deal in real estate, quickly rising in Fort Worth society as one of its largest landowners. He was a leading advocate for moving the county seat from Birdville.

“Was it true, the story about Fort Worth stealing a barrel of whiskey out of Birdville and giving it out to voters as incentive to get to the polls,” I ask.

“Just a legend,” he says. Or was it?

Peter, who turned down a number of overtures to run for governor, backed key projects like the Fort Worth Street Railway and the Texas & Pacific Railroad. By the 1880s and into the 1890s, his influence extended to building the city’s first stockyard and supporting countless cattlemen and business ventures that shaped Fort Worth’s growth.

“I was there that afternoon when the great concourse followed his body to its final resting place,” Alex says. “It was the largest gathering anybody can remember ever seeing to honor the dead in Fort Worth. I stood among his countless admirers, all of us mourning the loss of Fort Worth’s best friend and one of Texas’ greatest citizens.”

I follow Peter, who began to walk. I turned to find Alex, but he was suddenly nowhere to be seen.

“Another anti-secessionist was David Culberson in East Texas,” says Peter, before being interrupted. A very dapper man stood before me.

“He voted against it in the Texas Legislature,” says this new man, who takes over the story. “But, defeated, he served his state in the Confederacy. Good afternoon, I’m Charles Culberson. David Culberson was my father. He’s out in East Texas.”

Charles Culberson — who arrived in Oakwood in 1925 — has always intrigued me. He is in the Harrison plot, very near the mausoleums of Burk Burnett and John Slaughter, as well as K.M. Van Zandt.

Though his father went on to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives, the son grew up to become a darling of Texas politics — attorney general, governor, and a member of the U.S. Senate, where he served for almost 25 years.

Culberson’s mark as governor was a special session in 1895 to ban boxing. He had a Prohibitionist’s zeal against the sport.

“I summoned that special session not for spectacle, but for duty — to place upon our statute-books a law making prize-fighting a felony,” Charles says to me. “Such exhibitions, as practiced in many places, are incompatible with the morals and safety of our citizens. Texas must refuse to sanction cruelty under the guise of sport and must draw a firm line: If men wish to strike blows for gain, then law must interpose and forbid.”

That effort to stop the fight in Dallas between James Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons eventually turned to spectacle. In the end, Roy Bean held a fight between Fitzsimmons and Peter Maher on a sandbar in the Rio Grande, on the Mexico side, spitting in the face of the law and Charles Culberson.

“That exhibition upon the Mexican bank of the Rio Grande was not a triumph of sport but a mockery of law,” Culberson says, now seemingly preaching to me. “It was a deliberate attempt to evade the sovereignty of Texas and to flout the authority of this office. Let no man mistake it — when individuals stage such spectacles within sight of our soil, thumbing their noses at statute and order, they do violence not only to the letter of our law but to the dignity of the state itself.”

Culberson made his mark, however, in the Senate as a friend of President Woodrow Wilson. In 1912, he introduced Texas to Wilson, the rising political star, at the Texas State Fair in Dallas. It would lead to Texas going Wilson at the Baltimore convention and, ultimately, presidential triumph.

Once Wilson reached the White House, Culberson, and even more so his political rainmaker, Col. Edward House, became one of the president’s closest friends and most reliable allies in Congress. When the reform-minded Wilson needed a steady hand in the Senate, it was Culberson he turned to.

“I voted for him twice,” says Alex, having suddenly reappeared, of Wilson. Alex dabbled in politics. In fact, he was an alternate delegate to the state Democratic convention in San Antonio in 1916.

“That was an all-Wilson conclave,” he says. “The ‘Harmony Doctrine.’”

Culberson, looking a little annoyed at Alex’s interruption, supported Wilson’s efforts for a permanent peace through the Treaty of Versailles.

“Though my own fortunes waned, I left Washington certain that history would judge our failure to ratify the treaty as a lost opportunity for America to lead wisely in the world,” he says.

No one in Texas saw Culberson for his reelection bid in 1916, the first direct election in Texas of that august body. He was too sick to come back to campaign. Rumors of his attachment to the bottle swept across the lips of muckrakers.

“I heard the whispers, and I will not pretend I am without frailty,” Culberson says to me with the flair of a lawyer making a closing argument. “But I would remind those who judge that a man is not measured by his failings alone, but by his service to his state and country. If my hand has ever trembled from private weakness, it has never trembled in the discharge of my duty.”

He turns and walks away, never to return.

I’m suddenly on my own, the senator having beat a path to somewhere, and dear, ol’ great-granddad taking a break — I guess.

I’d always heard that Fort Worth’s greatest ballplayer was here somewhere, though I’d never found his gravesite.

Joe Pate was born in Alice, Texas, in Jim Wells County.

“Do you know who Jim Wells was,” says this young man in a Fort Worth Cats baseball uniform.

“I don’t,” I say to a guy — I’m getting used to talking to the dead — I’m guessing is Joe Pate.

“Me either,” Joe says. “I wasn’t there but a few years before we moved to Fort Worth.”

At Central High School — today we call it Paschal — Joe was a standout quarterback before turning to baseball. He went on to become a star pitcher for the Fort Worth Cats, where he spent eight seasons (1918–25) under legendary manager Jake Atz.

Pate won 30 games in both 1921 and 1924 — making him the only two-time 30-game winner in Texas League history — and added four more 20-win seasons during his tenure.

The Cats won five Dixie Series championships in six years with Pate as their ace, and in 1924 Amon Carter even took him to Washington, D.C., to meet President Calvin Coolidge after one of their victories.

“I’d pitched a lot of tough innings, but walking into the White House to shake hands with the President was something else entirely,” Joe says to me. “Mr. Coolidge wasn’t a man of many words — in fact, not surprisingly, he said very little. Baseball had carried a Fort Worth boy farther than I ever dreamed.”

In 1926, at age 34, Pate joined the Philadelphia Athletics under Connie Mack. He went 9-0 with a 2.71 ERA and six saves as a rookie, tying a major league record for most consecutive relief wins to start a career.

During his two years with the Athletics, Pate shared the clubhouse with future Hall of Famers including Ty Cobb, Al Simmons, Mickey Cochrane, Jimmie Foxx, Eddie Collins, and Lefty Grove.

“Ty Cobb was fierce, sharp as barbed wire, and he played every inning like it was the last out of the World Series,” he says. “Just to wear the same uniform was something I never forgot.”

After returning to Fort Worth in 1928, he played eight more years of minor-league ball before retiring. Later, he operated a newsstand and domino parlor.

“I thought running a newsstand and dealing dominoes would keep me busy, but truth be told, nothing ever filled the hole baseball left. Baseball wasn’t just what I did, it was who I was.”

Joe turns to the side as if something big were approaching.

There was something big approaching: a beautiful woman. Holy mackerel, I think to myself, as this glamorous young beauty walks toward us. She is wearing a long, form-fitting gown, its shimmering sequins shining brightly in this Texas sun. Her heels are, let’s just say, high.

“That’s Adrienne Ames,” Joe says to me.

“I am Adrienne Ames … once upon a time Ruth McClure of Fort Worth, Texas, but the world came to know me beneath the brightest lights.”

In the six years before her death, she was the voice of Hollywood and Broadway on WHN radio, broadcasting twice daily and interviewing leading celebrities.

“You reside here, I presume?” I asked.

“Yes,” she says.

The elegant Ms. Ames was often referred to as “the orchidaceous Miss Ames” and frequently listed among America’s best-dressed women.

After marrying New York broker Stephen Ames, she was introduced to Manhattan society. She continued her education, studying literature at Columbia University and art at the Metropolitan Museum. A vacation to Honolulu with her husband led to a detour in California, where striking photographs of her beauty caught the attention of Paramount executives. They offered her a contract without even a screen test.

“It still astonishes me,” she says. “A handful of photographs changed the course of my life.”

Ames went on to star in numerous films throughout the 1930s, including “Twenty-Four Hours,” “The Road to Reno,” “Two Kinds of Women,” “From Hell to Heaven,” and “George White’s Scandals.”

She also had a Hollywood track record in matrimony, marrying three times, the first to Texas oilman Derward Truax.

“She died in 1947 at 39,” Joe says. “I died the next year.”

The tallest obelisk in Oakwood Cemetery sits on the plot that houses the remains of Fort Worth businessman William Madison McDonald, a pioneer in every sense of the word, a leader of the Texas Republican Party for more than 10 years as the founder of its “Black and Tan” faction that sprung to life in the late 1890s.

That the obelisk faces the former Ellis Pecan Co., a former Ku Klux Klan hall, is no accident, at least according to lore. It was intentional, the placement of the monument, which he built some years before his death in 1950 at age 84.

“I’m not saying that’s true,” says McDonald, who has appeared in front of his memorial in the Trinity section of the cemetery. “I’m not saying it’s not true.”

McDonald rose to prominence as both a businessman and political leader, becoming, it is believed, the first Black millionaire in Texas.

“That’s true,” he says.

After the death of Norris Wright Cuney in 1897, McDonald assumed leadership of the Texas Republican Party. He forged a strong political alliance with Edward Howland Robinson Green, and together they led the “Black and Tans.” Though their control was challenged and briefly lost to the “Lily Whites” in 1900, McDonald and his allies regained influence in 1912 during the “Bull Moose” upheaval.

Alongside his political career, McDonald built a powerful business legacy in Fort Worth. With the backing of Black fraternal lodges, he founded the Fraternal Bank and Trust Company, which became the principal financial institution for Black Masonic lodges across Texas. This achievement cemented his reputation as both a savvy financier and a civic leader.

“I am most proud of the bank,” he says. “It was more than a business. With the support of our lodges, we created an institution that gave our community a measure of control over their own destiny. For years, it proved that Black enterprise could not only survive but thrive in Texas.”

McDonald had the obelisk erected as a memorial to his son, who died in 1918 while away at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

“The day I lost my boy was the hardest of my life. He was only 20, just beginning, full of promise, with a mind set on helping his community. I had dreamed of handing him the burden and the blessing of leadership, but God saw fit to call him home before his time.”

W. T. Waggoner was the kind of man who seemed larger than life. His fortune stretched across oilfields and cattle ranges, but his heart beat to the rhythm of hooves.

“A horse will tell you more about yourself than any banker ever will,” says Tom Waggoner, who is standing just outside his grand mausoleum.

I immediately look for a way to remember what he just told me.

Tom Waggoner was one of Texas’ most remarkable sons. He was raised on the unforgiving frontier and carved out distinction as one of Texas’ most celebrated cattle barons — who with his father built one of the largest cattle operations in Texas — and landowners.

On that land, he eventually found a lot of oil, becoming one of the richest men west of the Mississippi. His Wichita County lands sat atop one of the great oil pools of the Southwest, and while derricks eventually sprouted where cattle once grazed, he never lost his identity as a cowman.

He turned down offers in the tens of millions for his holdings, measuring success in the quality of herds, not in barrels of oil.

To Waggoner, cattle meant more than profit; they represented a way of life.

He still says to me on this day that it was water he was digging for, not oil, when crude appeared.

“I wanted water, and they got me oil,” he says of the memory. “I was mad, mad clean through. I said, ‘Damn the oil. I want water.’ Oil may fatten a man’s purse, but cattle feed a man’s soul. I’ll take the herd over the derrick any day.”

He poured his fortune into causes that mattered to him: strengthening Fort Worth and supporting education and, perhaps most famously, realizing his dream of building Arlington Downs — one of the finest horse racing tracks in the nation. There, his passion for good horses found a stage equal to his ambition.

Despite his immense fortune, Waggoner never traded simplicity for extravagance, as I witness on this day. He’s plainspoken, generous, and as old-fashioned as an old shoe.

He was a civic leader, pouring money and energy into his adopted city, Fort Worth. He funded dormitories and fine arts buildings at Texas Woman’s College, and he erected two of downtown’s landmark office towers — the Dan Waggoner and W. T. Waggoner buildings.

“Because in the end,” Tom says, “we will be judged in how we treated each other.”