Ricardo and Laura Rodriguez have lived in their Westside home for 36 years. Like many houses in the city’s historic Westside neighborhood, the couple’s home lacks central air conditioning, relying on individual units to fight off San Antonio heat.

“It’s hard to have all of them on at one time, because those bills [add up],” Ricardo, who is disabled, said. “With one check a month, it’s hard.”

In their living room, a small white sensor sucks in air and measures temperature and air quality. Another hangs above their porch outside. When the sensors shine red, indicating poor air quality, the couple opens their windows and turns fans on.

West Side resident Ricardo Rodriguez says relying on individual air conditioning units on warmer days is costly for him and his family. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

West Side resident Ricardo Rodriguez says relying on individual air conditioning units on warmer days is costly for him and his family. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

The sensors came courtesy of University of Texas at San Antonio researchers studying extreme heat throughout the city. Their research so far has been focused on the West Side, a historically underserved community and urban heat island, where temperatures can soar and turn poorly built homes into furnaces due to an overabundance of concrete and lack of green space.

The researchers are using the sensors, artificial intelligence and “digital twin” technology to map out how heat and poor air quality is felt in the neighborhood, and how to best mitigate the impacts with limited resources.

Esteban López Ochoa, an associate professor of urban and regional planning at UT San Antonio and lead researcher on the project, said that indoor temperatures in some homes can rise above 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer.

Ricardo Rodriguez and his family used to live in this house situated in an urban heat island area on the West side of San Antonio before moving to his current home across the street in the ’90s. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Ricardo Rodriguez and his family used to live in this house situated in an urban heat island area on the West side of San Antonio before moving to his current home across the street in the ’90s. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

“We did surveys on the residents, asking them how you’re feeling, what kind of chronic conditions do they have?” Ochoa said. “Many of them have reported that year over year, they are having heat strokes, and they’re just waiting for the next one to happen.”

Heat equity

Ochoa, who grew up in Chile and earned his doctorate in Illinois, said that he had never experienced extreme heat like this until he moved to San Antonio in 2012. He was astonished to learn that some communities in the city lived through the sweltering heat with precarious to non-existent air conditioning in their homes.

Heat maps created using the researchers’ data have shown that the inner neighborhoods of San Antonio just outside downtown tend to fare worse when it comes to the urban heat island effect.

The elevated temperatures are felt disproportionately in disadvantaged communities where poor housing conditions offer little relief from the Texas heat.

For many residents, running AC constantly can come with “an avalanche of problems,” said Luissana Santibanez, an organizer with the Coalition for Dignified Housing, “because then they have really high electricity bills, over $400 a month sometimes.”

The first phase of Ochoa’s research involved taking stock of housing conditions on the West Side, and developing a rating system that could predict which homes were more likely to be demolished. The houses in the poorest conditions — with less insulation, poor foundations, cracking windows and an array of other issues — would at times get hotter inside than the outside temperature, Ochoa said.

When the sun went down and the asphalt stopped radiating heat, residents’ homes would stay hot into the night. “They couldn’t get a break from the heat,” Ochoa said.

The researchers then started placing small, $300 sensors inside and outside of residents’ homes measuring air quality and temperature, alerting residents when the air quality or temperature reach certain levels.

West Side resident Ricardo Rodriguez talks about the PurpleAir sensor that monitors air quality and temperatures installed on his porch at his home on Sept. 29, 2025. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

West Side resident Ricardo Rodriguez talks about the PurpleAir sensor that monitors air quality and temperatures installed on his porch at his home on Sept. 29, 2025. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

The sensors also offer researchers better, more specific ground-level data. Instead of relying on satellite data, the researchers’ heat maps and city-wide temperature calculations incorporate specific measurements taken at the neighborhood level.

“Just like the physician takes your temperature, we’re going to put thermometers basically across the city,” Ochoa said. “I really wanted to see what are the interior conditions versus the exterior conditions, and that’s why we wanted these sensors to really help us work on that.”

Digital twins

Digital twin technology was first developed by NASA in the 1960s to model spacecraft for the Apollo missions. By creating a digital replica of physical spaces or objects, researchers can run simulations and test how different interventions might produce different results.

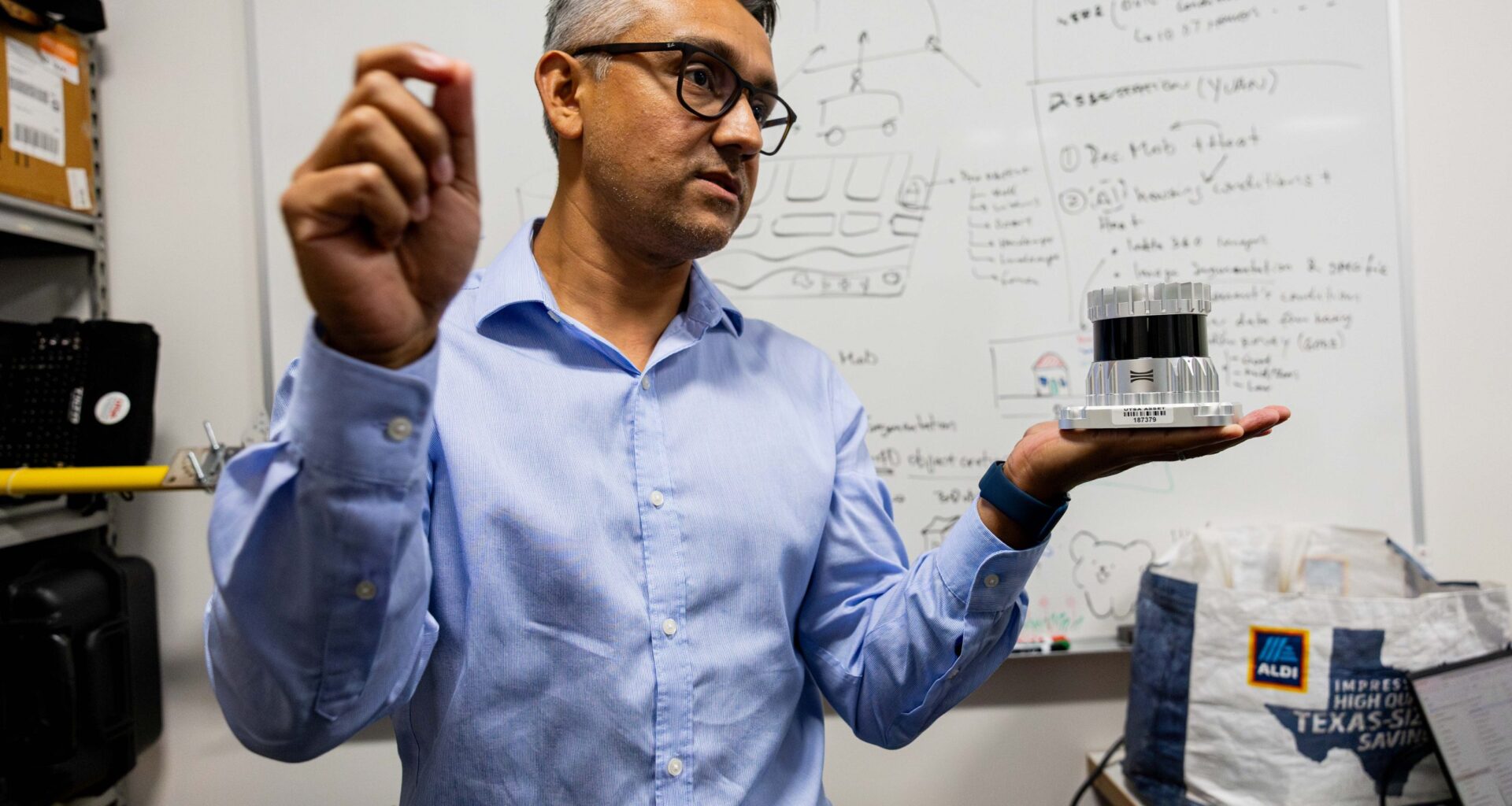

Using sonar-like technology known as light infrared radiant detection, the UT San Antonio researchers analyzed 600 Westside houses, creating digital replicas of the inside and outside of residents’ homes. Then, by running AI-powered simulations in the three-dimensional digital copies of the homes, researchers can pinpoint solutions, like extra insulation in specific parts of the home, for example.

Esteban López Ochoa, a UT-San Antonio associate professor of urban and regional planning, demonstrates an AI program used to map a “digital twin” of resident homes for their research. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Esteban López Ochoa, a UT-San Antonio associate professor of urban and regional planning, demonstrates an AI program used to map a “digital twin” of resident homes for their research. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

That’s important, Ochoa explained, because over-weatherization can cause problems for residents in the winter. If a contractor adds too much insulation, summers might become more bearable, but the homes will also become ice boxes in the colder months, unable to permeate heat. And, it’s helpful for residents with lower incomes to know which changes might give them the best bang for their buck in cooling down their homes.

The research has been ongoing since 2024. Ochoa says that they’re now expanding the program to other heat islands and underserved communities in the South Side and East Side. As more data comes in, Ochoa hopes to see the research used as the basis for new city policies and efforts geared toward mitigating extreme heat.

“It’s not going to get cooler,” Ochoa said. “If we don’t do anything now, 10 years from now, we’re going to really be seeing the consequences. I don’t want to sound alarmist or extremist, but this may be a less inhabitable city than it is right now. Having a large portion of the city living in extreme heat without appropriate ways to cope, it’s just not something that we should be known for.”