Fourteen years ago, Dallas’ second-oldest public high school became an official Dallas landmark, joining the likes of the Majestic Theater, the Adolphus Hotel and Dallas City Hall — the old one on Harwood Street, mind you, not the Brutalist building on Marilla Street that a majority of the City Council now appears eager to abandon to the highest bidder whose last name probably rhymes with “Adelson.”

W.H. Adamson’s historic designation, the result of a long, ugly tussle between Dallas Independent School District officials and preservationists and a passionate alumni association, was meant to spare the 110-year-old school from demolition. But as I wrote in August, no amount of rules and regulations could save the former Oak Cliff High School from DISD.

Demolition by neglect, it’s called, the fine art of looking the other way as the windows shatter, the plywood fades and peels away, outsiders make their way inside. It was only a matter of time before the district made official what it’s done so casually for years.

On Oct. 24, DISD finally told Dallas City Hall it wants to demolish Adamson, claiming the building is an “imminent threat to public health or safety.” The “building is not structurally sound along the south façade,” says the certificate of appropriateness filed with the city in advance of the demolition permit it hopes to secure.

This is how the old Adamson campus looked on Aug. 29. DISD crews eventually replaced the fallen chain-link fence, covered the broken windows and tried to clean the spray paint off the historic marker shortly after we wrote about how the district allowed the historic landmark to become an eyesore.

Robert Wilonsky

DISD, which didn’t comment for this piece, has maintained it will cost more than $102 million to keep the building standing. The CA doubles down, insisting that “the district has been unable to keep people out of the building and costs to repair are greater than what the district can responsibly provide.”

Opinion

So down, down, down it must come — the same thing I heard Monday sitting in City Hall from staffers and several council members lamenting the woeful state of The People’s House on Marilla. Adamson, like City Hall, didn’t have to fall apart all at once. The people in charge let it happen, slowly, willfully, over decades. And now they rush to bury the evidence in the landfill.

We should be embarrassed. But in Dallas, it’s just business as usual. Tear it down. Tear it all down.

The Landmark Commission will discuss Adamson on Dec. 1, but it has already signaled to the district it won’t take kindly to requests to raze the campus that also sits on the National Register of Historic Places. Preservation Dallas, too, is joining the fight with a meeting scheduled for this week. Sarah Crain, its new executive director, told me Monday they’ve been trying to engage DISD but to no avail.

Apparently, DISD crews had a hard time removing the spray paint from the historic marker planted in front of old Adamson, a local and national landmark.

Robert Wilonsky

“What’s heartbreaking about Adamson is that everyone has watched it rot over the last years, and this demolition by neglect conversation doesn’t serve the DISD,” she said. “They could have invested in the space and shined a light on what DISD is able to do with its historic schools or partnered with someone who can. But we haven’t had great communication from DISD about what their ultimate intent is other than to tear it down.”

The city began landmarking historic structures in 1974, after it was proposed in then-Mayor J. Erik Jonsson’s 1966 Goals for Dallas program that also gave us I.M. Pei’s City Hall. And since then only five buildings have been demolished — three of which were claimed by fire, including most recently the Ambassador Hotel. I know people who won’t shop at the Kroger on Mockingbird Lane and Greenville Avenue where Dr Pepper’s national headquarters once stood, still upset about its long-contested demolition in 1997, after which Dallas tightened its rules for erasing history.

“The city used to make life difficult for property owners” who let their historic properties deteriorate, said Marcel Quimby, the preservation architect who helped the Adamson Alumni Association secure the campus’s addition to the list of Dallas’ historic landmarks. “That’s how we saved Dallas High School back when the building inspection group was doing the right thing, citing them for vagrants, for fires, for letting the façade deteriorate. Eventually the out-of-town owners sold because they got tired of fighting the city.”

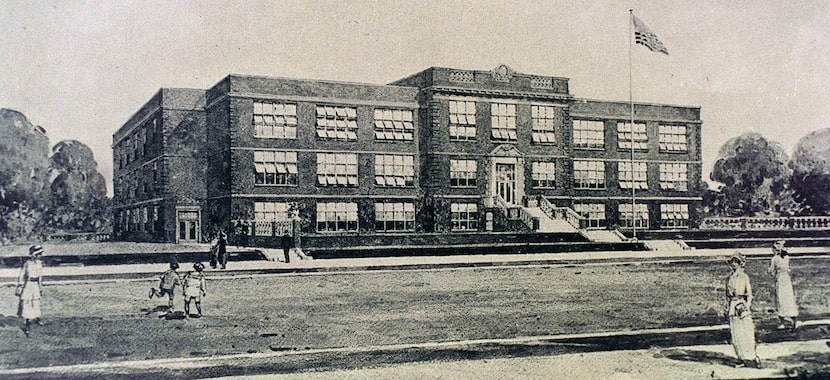

A drawing of Oak Cliff High School, which was built in 1915, opened in 1916 and eventually became A.H. Adamson High School, now a local and national landmark

Randy Eli Grothe / 99071

And eventually Dallas High School, Dallas’ first public high school, was resurrected, transformed into office space in 2018.

The 123-year-old Davy Crockett School, another city landmark the district allowed time to trash, was similarly spared the wrecking ball when DISD offloaded it to a developer who converted the historic hulk on Carroll Avenue into 52 luxury apartment units.

But the story is different at Adamson. The city never once went after the district for allowing it to rot. City Attorney Tammy Palomino told me in August that “the City Attorney’s Office has not received a referral from code enforcement.” Maybe because, according to the city’s own Historic and Cultural Preservation Strategy adopted just last year, there’s just one code compliance officer assigned to caretake historic structures and districts. As a result, said the report, “The system is … not equipped to handle any increase in the number of landmarked properties or historic districts.”

Erik Jonsson, who brought Dallas a very modern City Hall, also believed old buildings, spared and well maintained, enhanced the visual character of the city. He believed, according to Goals for Dallas, that they could and should give the relatively new city a “sense of history, identity, diversity and beauty.” Anyone who’s driven past Adamson in the past few years has seen that beauty slowly transformed into blight.

Linda Pauzé, the alumni association’s vice president who spent 18 years teaching English at her alma mater, found out over the weekend that the district had finally begun demolition proceedings with the city. She wasn’t surprised. Just sad — “sad that there’s been so much neglect that now they feel like this is the only solution.”

Underneath all that new plywood, behind all that chain link, is a campus that looked like this as recently as August 29.

Robert Wilonsky

“It’s sad,” former DISD Superintendent Michael Hinojosa told me Monday. “I drive by it every few months, and it’s just sad.”

Hinojosa began his career there, as coach and educator. His family attended Adamson. Yet during his tenure running the district, Hinojosa fought against Adamson’s designation, a bruising battle between the district and the Adamson Alumni Association and preservationists that lasted from the spring of 2008 until the fall of 2010, when he suddenly surrendered and allowed the city to add the high school to its historic inventory.

“I fought it even though I love Oak Cliff, even though my brothers and sister and I went there, even though it was personal,” he told me. “I wanted to keep it. But I was also management, responsible for running the place, and when I learned the cost and complexities of historical designation, reluctantly I agreed with the team that we needed to fight it.”

He said he relented only when he realized that “even if we won, we were gonna lose, so I said, ‘Let’s try to make this work.”

Old Adamson looks much different today than when we last visited in August. But the district’s position remains unchanged: The historic high school must be town down.

Robert Wilonsky

At the time, he hoped the district would transform the old Adamson building into a “Digital Arts and Creative Technology campus” for students who couldn’t get into Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. District officials said recently they spent $6 million on site studies and designs for such a school, but that they couldn’t find contractors willing to do the work, given Adamson’s condition.

Hinojosa said he was “disappointed that this great idea will not come to fruition on this campus.”

He also mentioned that he has a recurring dream: “I am a custodian in that building, in Adamson.” I asked why. “Because I knew that school like the back of my hand. I worked there longer than any other building.” And it hurts him to know that one day soon he might drive past Adamson, and it will no longer be there.

“I get it,” he said. “A lot of districts have to close schools, repurpose them, tear them down. But there’s also a connection to the past. It looks like Woodrow, Sunset, North Dallas. I get it. But it doesn’t take away that feeling, that pain.”