This story was updated to add new information.

As the Inner Harbor desalination debate drifts from the forefront into the background of the region’s water wars, a new battle has been born: who controls the aquifer and the millions of gallons of groundwater that resides beneath the soil.

A dispute has been unfolding in recent months between Nueces County property owners and city of Corpus Christi officials — each pursuing separate regulatory jurisdictions that would hold authority over two city-owned well fields located outside city limits in the county.

Property owners backing creation of a proposed Nueces Groundwater Conservation District have been raising questions on the potential that the municipally owned and operated wells may interfere with privately owned wells that, in some cases, are the exclusive source for daily living needs for residents and for livelihoods of farmers.

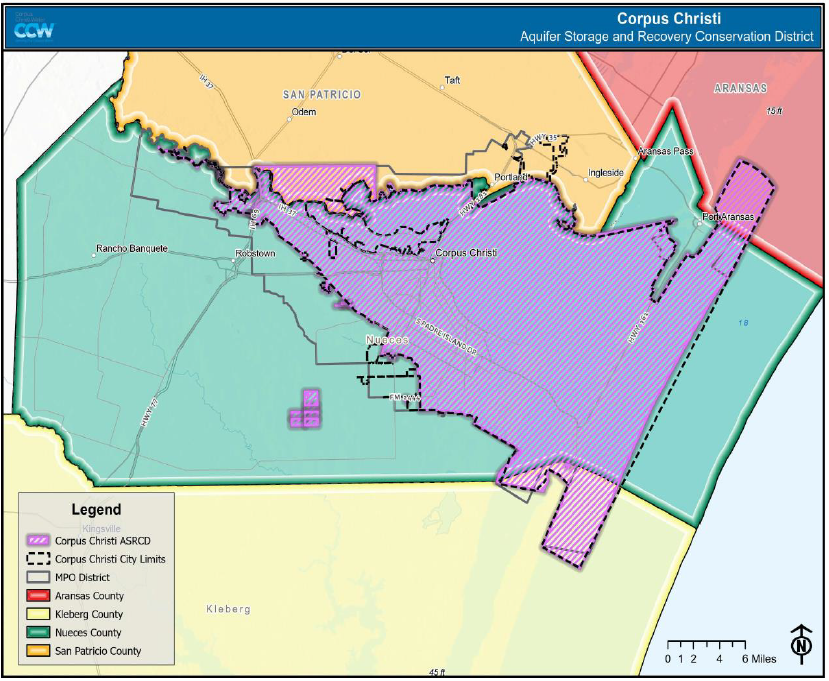

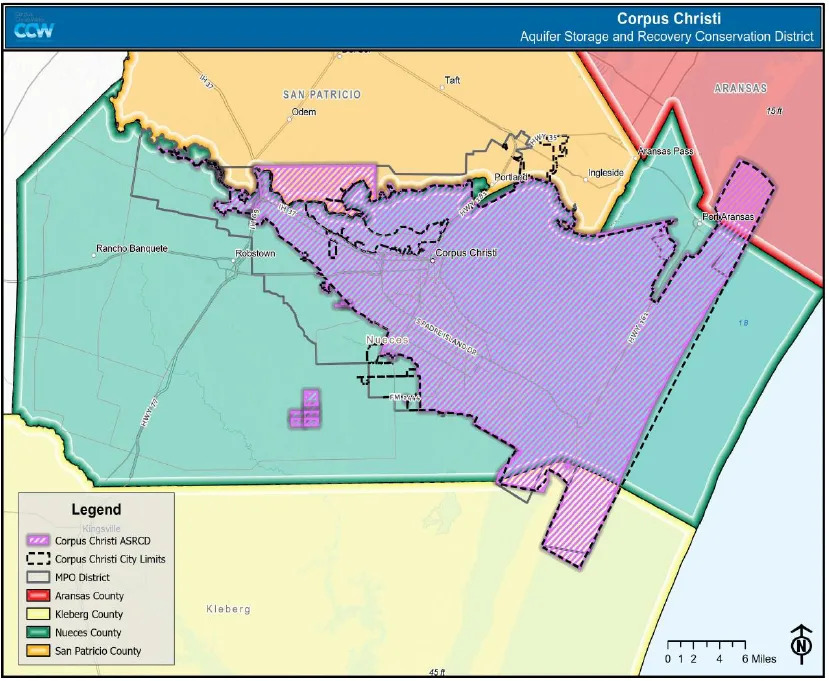

This map shows the boundaries of the existing Corpus Christi Aquifer Storage and Recovery Groundwater Conservation District.

City officials, meanwhile, have asserted that it is not currently expected the municipally owned wells — pumping groundwater from below roughly 260 acres of city-owned properties — will impact privately owned wells.

Months into petitioners’ pursuit of a Nueces GCD, the well fields were officially absorbed into an existing district — the Corpus Christi Aquifer Storage and Recovery Conservation District — by a unanimous board Nov. 4, after nearly one dozen people spoke in public comment opposing the move.

The push to join the Corpus Christi ASRCD stemmed, in part, from a desire to be regulated, staff told the City Council in an Oct. 21 meeting. Making the properties a part of the Corpus Christi district would more swiftly enable regulation and protection of the natural resources, compared with the timeframe that a Nueces GCD could be formed.

That route may also allow the city to more firmly control the water supply, which could be hindered if under the purview of the proposed Nueces GCD.

The boundaries of the existing Corpus Christi ASRCD, with few exceptions, have been confined to the corporate city limits.

Among concerns relayed by Nueces County property owners are the possibilities of subsidence, as well as drawdown of private wells.

The move to include the properties in the Corpus Christi ASRCD amounts to a power play by the city, some critics have said.

Property owner Tommie Sue Arnold described the city’s well field efforts as having “the sole purpose of taking from us,” asserting that municipal operations have the potential to dry up private wells, deteriorate water quality and “destroy our rural livelihood with big-city greed.”

“Don’t tread on our rural water resources,” she told the board. “Stay in your city limits lane.”

The idea, according to a presentation made before the board by Brett Van Hazel, water supply projects director for Corpus Christi Water, is to manage the city’s groundwater with “consistency and predictability.”

Groundwater is integral to fulfilling basic needs of rural property owners, but it also holds a high-stakes place in helping to close the gap on available water for the region as yearslong drought continues to bear down.

City officials hope that once the project is fully developed, as much as 28 million gallons of groundwater per day could be integrated into the overall water supply.

The city is expected to return to the board with specific requests for permitting — a process expected to “address any concerns that folks have over the construction and operation of those wells,” said Jeff Edmonds, a board member and the city of Corpus Christi’s engineering director.

There may be a perception that “the city does not care about their issues and concerns, and from my perspective that does not map onto reality,” he said, adding that the city has made efforts to minimize any impacts to off-site wells.

CCW is responsible for about 500,000 customers, extending beyond those in the city of Corpus Christi.

“It’s people within the region that rely on us to supply their water,” he said. “Who should control this district and who should set regulations about the use of this groundwater — is it the (ASRCD) or would it be a district comprised of rural interests who are only interested in limiting the amount of pumping of groundwater?”

Tapping into groundwater

Groundwater has been untapped for decades by the city of Corpus Christi, which has historically relied on surface water sources, primarily Lake Corpus Christi and the Choke Canyon Reservoir.

That changed last year, as the combined capacities of the water bodies continued their descent past the 20% mark. They now measure at about 11%, according to city data.

Late last year, city staff unveiled what was a temporary strategy: revisiting groundwater wells along the Nueces River, a method that had similarly been used in the 1950s and as recently as the 1990s, to supplement supply.

City officials have described it as a short-term solution, patching the forecast water supply deficit pending longer-term projects coming online.

One that had been expected, but has since been indefinitely paused, was the controversial state-backed desalination plant on the ship channel that had been proposed to treat as much as 30 million gallons of water per day.

What is known as the Eastern Wellfield — about 16 acres along the Nueces River near County Road 73 — currently comprises eight wells producing as much as 10 million gallons of water per day, Van Hazel told the board on Nov. 4.

As many as 12 wells are planned for the Western Wellfield, he said.

The roughly 250-acre property is a jog away from the Eastern Wellfield, the site near County Road 666 and Northwest Boulevard.

Currently, there are three wells developed on the Western property, Van Hazel said. Combined with the installation of as many as nine wells, the well field may produce as much as 17 million gallons per day.

The well field volumes are sustainable, city officials have said. At least $21.5 million had been spent on the projects as of early October, according to a city memo.

Although there are state permits restricting the volume of water that may be conveyed into the Nueces River, groundwater is currently pumped under what is known as a “rule of capture,” said Esteban Ramos, CCW water resources manager and general manager of the ASRCD.

The rule of capture is something of a default when a property is not within the bounds of a district.

Laid out in Texas law, it essentially means that property owners own not only their land but also the water underneath it.

Under a GCD, board members can regulate groundwater use, city officials have said, endowing the ability to approve production and drilling permits, well spacing, and assessment of export and transport fees.

A GCD may have the power to shut down wells entirely, City Attorney Miles Risley told the City Council last month.

A proposed groundwater district

Rural property owners have been watching the city’s steps as officials have debated and decided water supply projects.

The Inner Harbor situation caught attention, said Trey Cranford, a representative of the movement for a Nueces GCD, in October.

“We felt that (there) was a need to look at protecting groundwater because that was going to be the low-hanging fruit,” he said. “So we started researching on how to create a water conservation district.”

The pushback gained profile with an early September announcement to the City Council of the hand-delivery of a petition to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to create a Nueces GCD.

Filing the formal paperwork represents the kickstart of a lengthy, complex administrative and legal process.

The petition is currently under TCEQ review, Cranford said on Nov. 4.

“They should only be taking their fair share,” he told the Caller-Times in October. “As it is, they’re coming out into the county, taking residents of the county’s water — which, again, is not being a good neighbor.”

The ASRCD board

The city’s endeavor to become part of the ASRCD, some critics have said, is an attempt to quickstep ahead of a potential Nueces GCD.

The ASRCD’s role has been questioned by skeptics.

It follows the same rules as GCDs and is technically a separate entity from the city but is managed under an interlocal agreement between the city and district, officials have said.

The board nominates its members, who are then submitted to the City Council for approval, according to staff. Serving in four-year terms, the members are required to live within the ASRCD boundaries.

All its current members are employed at the city of Corpus Christi.

The composition of the board is problematic and poses a conflict of interest, Cranford said in October — in essence, creating a situation that lacks transparency and in which the city would be regulating itself.

Several council members, responding to criticism, endorsed last month placing non-city staff members to serve on the board. The first opportunity to do so will be at the end of December, according to city records.

Edmonds, one of the five board members, has had no “communication from management or City Council about how or what we should be doing as part of this (ASRCD) district board,” he said.

The intent is “to be good neighbors … good citizens, good custodians of the resource,” he said, adding that board members are “interested in striking an appropriate balance.”

“There are individuals out there that are concerned over our use of groundwater and that may not be interested in striking the appropriate balance,” Edmonds said. “They might be interested in not striking a balance at all. They might be interested in only limiting or minimizing our use of the groundwater resource.”

Other ASRCD board members are Bill Mahaffey, director of gas operations; Nick Winkelmann, CCW interim chief operating officer; Dan McGinn, interim assistant city manager; and Ryan Skrobarczyk, director of intergovernmental relations.

Mahaffey, reached the afternoon of Nov. 6, said he had not been directed on how to vote, instead making his own decision on what he believes is right.

McGinn, Skrobarczyk and Winkelmann could not immediately be reached.

Private well concerns

While it’s not currently expected that the municipal wells would impact those existing in private use, data is continuing to be collected and the quality and quantity of the well water is being monitored, said City Manager Peter Zanoni on Oct. 27.

“Should there be changes of substance in the volume of water, we’ll adjust our program accordingly,” he said — meaning, for example, pumping a lower volume of water or revising the timespans of pumping.

If city operations were to compromise private wells, it is planned that mitigation would be offered, according to officials — for example, relocating wells or drilling them to a lower depth.

A well assistance program hasn’t yet been established, but “being good neighbors and a smart operation, we have to contemplate that we would need something like that if there was an issue that came up,” Zanoni said.

Cranford has dismissed the idea that the city’s wells won’t impact private wells.

The outcome of the Corpus Christi ASRCD meeting was expected, he said Nov. 4, but the situation isn’t resolved with the decision made by the board.

“Every action has a consequence that goes along with it,” he said. “So moving forward, there will be other actions that we have to take.”

This article originally appeared on Corpus Christi Caller Times: A battle has been born over Nueces County’s groundwater. Here’s why.