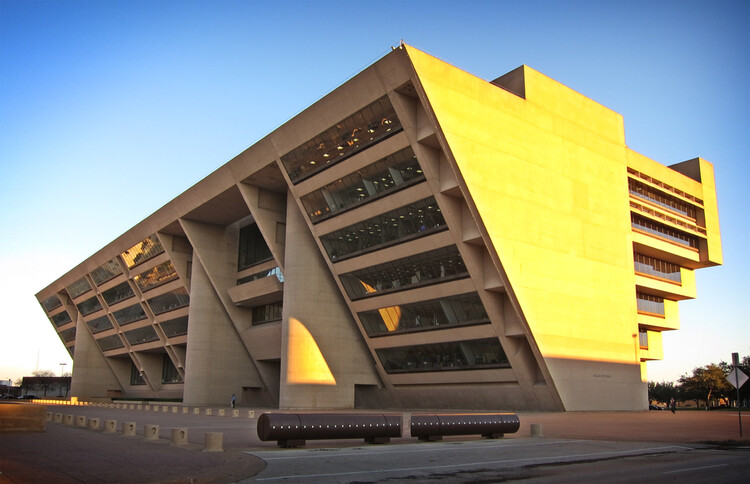

I.M. Pei & Partners Dallas City Hall. Image © Neff Conner via Flikr, under license CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

I.M. Pei & Partners Dallas City Hall. Image © Neff Conner via Flikr, under license CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1036025/dallas-evaluates-repair-and-demolition-options-for-im-peis-modernist-city-hall

Since August 2025, debate has intensified in Dallas, United States, over the future of one of its modern landmarks: I.M. Pei & Partners’ Dallas City Hall. This month, the Dallas City Council will continue weighing whether to repair, sell, or demolish the 47-year-old building, following growing concerns over long-deferred maintenance and the need for major investment. In late October, council members began public listening sessions and committee meetings to gather resident input. Preservationists and some council members urged a full study of repair options and historic landmarking, while others emphasized fiscal and operational concerns.

Supporters of preservation stress the building’s civic and architectural significance, while those advocating for demolition point to high maintenance costs and the redevelopment potential of the centrally located site. A petition to “Save Dallas City Hall,” calling on council members to halt demolition plans and commission a transparent renovation study, remains open for signatures. Meanwhile, the mayor has said he wants to review all the facts before taking a position on whether the city should relocate or invest in repairs. The case adds to the growing list of modernist icons worldwide facing uncertain futures, sparking broader cultural debates about civic heritage and public infrastructure.

The Dallas City Hall building is widely recognized as a distinctive example of Brutalist architecture in the United States. Designed by I.M. Pei & Partners and built between 1972 and 1978 on an 11.8-acre site near downtown, the structure encompasses nearly one million square feet, including more than 374,000 square feet of office space, two levels of underground parking for 1,426 cars, and public facilities such as the Council Chamber, Flag Room, and Great Court. Its signature inverted pyramid profile features six stories that widen as they rise, with the cast-in-place concrete façade sloping outward at 34 degrees. Each floor is approximately nine feet (about nine meters) wider than the one below. The architects described the project as an “inseparable combination of building and park,” deliberately diverging from the typical high-rise corporate model to provide significant open public space.

Related Article Dialogue with the Code: Calibrating Standards for Adaptive Reuse to Thrive

Beyond its architectural features, the building holds social significance as an emblem of Dallas civic identity. It replaced the Old Municipal Building that served as both City Hall and Police Headquarters, and where John F. Kennedy’s alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, was shot by Jack Ruby on November 24, 1963. Pei’s City Hall played no role in that event, though the two buildings are often conflated in public memory. Since its opening, the City Hall plaza, integral to Pei’s design, has hosted protests, parades, and public gatherings, becoming one of the first large-scale open civic spaces in the city. Over nearly half a century, the building has become a recognizable symbol of Dallas, appearing in films such as RoboCop (1987) and Solange’s When I Get Home (2019).

However, despite its historical and architectural significance, reports indicate that the building shows clear signs of deteriorating infrastructure, ranging from water leaks to failing electrical systems. City staff and journalists have for years noted underfunding for municipal facilities, with estimates for necessary upgrades ranging widely, from about $60 million to $345 million. Faced with this reality, efforts to secure historic protection began earlier this year. In February 2025, members of the Landmark Commission voted to initiate local historic-landmark designation for City Hall, and in March the Commission voted unanimously to move the designation process forward.

In August 2025, the mayor directed the City Council Finance Committee to evaluate City Hall and identify the most “fiscally responsible” options for its future, which formally launched the current review. This opened a new public debate balancing cultural significance against escalating maintenance costs. In October, city staff presented updated assessments showing higher repair estimates than previously contemplated, with some projections suggesting that repair and ten-year operational costs could reach several hundred million dollars, depending on the scenario. These numbers intensified discussions about repairing or demolishing the building, relocating municipal government, and potentially selling the downtown property.

Some city leaders argue that selling the land, located next to a new convention center scheduled to open in 2029, could unlock valuable redevelopment opportunities. Among the possibilities under discussion is a new arena for the Dallas Mavericks and Dallas Stars, both of which are exploring locations for a future venue as their leases at the American Airlines Center expire in 2031. The mayor has stated that he wants both teams to remain in Dallas. “Doing away with a historic building to create an arena is an extremely Dallas way of doing business,” historic preservationist Ron Siebler told The Dallas Morning News. Petitions and social-media campaigns advocating preservation counter these arguments, emphasizing the building’s cultural importance and noting that, even if renovation costs are high, they would likely remain lower than the combined costs of demolition and new construction.

In early November 2025, a series of city meetings accelerated the debate. On November 3 and 7, a Special Called Joint Meeting of council committees reviewed the “State of Dallas City Hall” briefing, with staff providing follow-up memoranda detailing repair costs and potential scenarios. On November 4, the Council’s Finance Committee recommended that the full Council formally evaluate alternatives to the existing building, including repair, relocation, sale, or other real-estate and operational options. This process culminated on November 12, when the City Council voted 12–3 to direct staff to pursue those evaluations, a decision widely interpreted as placing the Pei-designed landmark in jeopardy and triggering a surge in public response. In reaction, preservation petitions, op-eds, expert commentary, and social-media campaigns intensified, while organizations such as DOCOMOMO-US publicly listed the building as threatened.

Side view of Dallas City Hall. Image © Daquella manera via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

Side view of Dallas City Hall. Image © Daquella manera via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0

The Landmark Commission’s pending historic designation, combined with the Council’s exploration of alternatives, has created a legal and political tug-of-war between preservation and fiscal priorities. A final decision by the City Council is expected by year’s end. This situation mirrors other recent cases in which the costs of maintaining modernist buildings are weighed against their cultural and architectural importance. Earlier this year, a citizen-led campaign in Japan proposed new uses for Kenzo Tange’s Kagawa Prefectural Gymnasium, which has faced demolition since February 2023. In June, Melbourne residents successfully secured an extension of Tadao Ando’s MPavilion until 2030, despite its original designation as a temporary structure. A comparable example in the United States is Boston City Hall, designed by Kallmann, McKinnell, and Knowles and completed in 1968. Once widely criticized as inhospitable and inefficient, and repeatedly proposed for demolition, Boston ultimately chose to renovate and revitalize the structure, demonstrating how contested Brutalist landmarks can be adapted for a sustainable future.

A view of Dallas City Hall from the GeO-Deck of Reunion Tower in Dallas, Texas (United States). Image © Wikimedia user Michael Barera licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

A view of Dallas City Hall from the GeO-Deck of Reunion Tower in Dallas, Texas (United States). Image © Wikimedia user Michael Barera licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 View of Downwtown Dallas from Dallas City Hall. Image © Kent Wang via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0

View of Downwtown Dallas from Dallas City Hall. Image © Kent Wang via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0 Dallas City Hall, front (north) exterior. November 30, 2010. Image © David R. Tribble via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Dallas City Hall, front (north) exterior. November 30, 2010. Image © David R. Tribble via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0