No doubt, there are more pressing issues than a long-vacant South Dallas landmark adjacent to an even-longer-abandoned cemetery where the oldest graves date to the late 1800s. Like, say, the car wash and convenience store down the street on Second Avenue, a five-minute drive from Fair Park, which the city attorney’s office alleged in an August lawsuit is “overrun by individuals looking to hang out, play loud music, grill, drink alcohol, use and sell drugs, make a quick buck detailing cars, or even reside on the property.”

That seems important. But also pretty … familiar, let’s say. Especially the part where the car wash and convenience store owner, Elgin Allen III, disputes the city’s allegations, insisting in newly filed court documents that “he cannot control third-party criminal acts beyond his authority.” Allen’s asking for the city’s help. The city’s asking for a temporary injunction. If I had a nickel.

Meanwhile, a block south sits what’s left of the Lee G. Bilal Building, a national landmark that locals long ago boarded up and let fall apart and fade away. It’s on its fourth owner in a decade — the latest, apparently, “a very secretive billionaire [who] makes so much money he just takes the cash and buys real estate instead of putting money in banks.” That’s according to the very secretive billionaire’s tax attorney.

Behind the building, off Second and Carpenter Avenue, sits one of this city’s oldest and most neglected burial grounds, the unmarked Lagow Cemetery surrounded by chain link and usually buried beneath fallen tree limbs and high grass.

Opinion

Tuesday morning I visited the dead and righted a few overturned headstones, including one belonging to a girl who lived for only seven months more than 120 years ago. A woman who moved onto Carpenter in August 2024 told me she’s only seen crews cleaning the cemetery once in the last year. She said, too, that kids often cut through the overgrown “orphan cemetery” and jump over the fence to break into the Bilal Building.

All of this land — the Bilal building and the burial ground — once belonged to Richard Lagow, for whom the South Dallas street is named. In fact, the building was originally constructed in 1912 as Richard Lagow Elementary School before it was converted into the McGaugh Hosiery Mills in 1931.

A 1946 rendering from The Dallas Morning News archives of the building still standing at 4408 Second Ave.

The Dallas Morning News

The stockings plant expanded in 1946, and in 1950, there was a lawsuit alleging that building was interfering with cemetery operations, which was eventually settled by Judge Sarah T. Hughes, 12 years before she swore in Lyndon Johnson on the Love Field tarmac. By 1953, the building had become home to Cotton Belt Gin and Mill Supply.

There’s an old saying: Every house tells a story. In South Dallas, it often seems like every block writes a novel.

Thrice in recent weeks I’ve driven by that litigated convenience store and car wash — which is always empty, just my luck — and landed in the Bilal parking lot, across the street from the J.J. Rhodes Learning Center. The for-sale sign planted in 2018 is still there, promising “historic redevelopment” on this expansive property. But not so much the building’s decorative top, which seems to have fallen off in chunks since my last visit in, well, 2018. Its windows have been boarded up for so long the plywood’s faded to gray. A graffiti-violation notice from April is taped to one of its doors.

This newspaper used to write about the tumbledown building all the time, named for its one-time owner — a Booker T. Washington High School graduate and World War II veteran born Lee Gilbert Brotherton, who, in 1947, became one of the first Black cops in Dallas since the early 1900s. Brotherton, who converted to Islam in the 1970s and rejected his family name because of its slaveholding heritage, owned this building and many more when, in 2006, the 87-year-old died of a heart attack at the Dallas Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

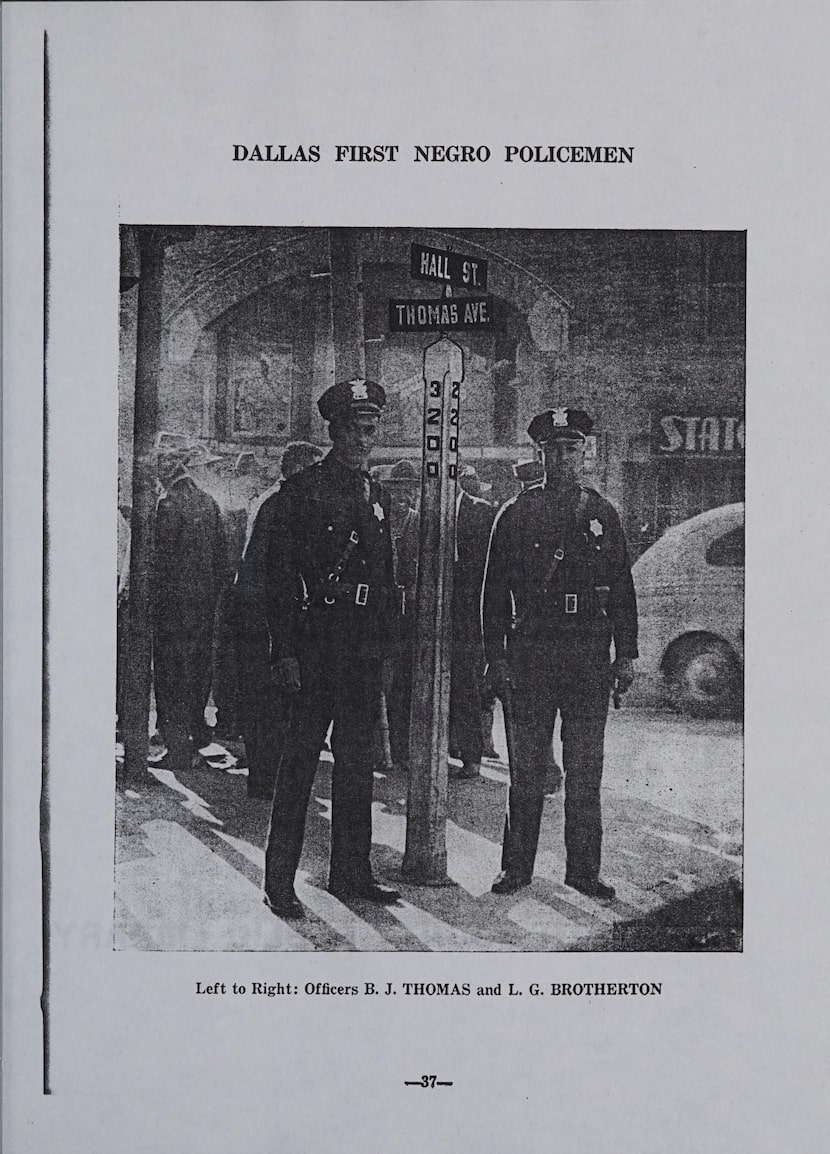

Benjamin Thomas and Lee Brotherton (later Lee Bilal) became Dallas police officers in 1947, the first Black cops in town since the early 1900s. They were assigned to the State Thomas neighborhood, as evidenced by this photo from the Negro City Directory published by the Dallas Negro Chamber of Commerce.

Internet Archive

Bilal was a beloved figure in this city, businessman and civic leader among his numerous bona fides. But it figures that in Dallas, the only thing to bear his name is a rotten building that was added to the National Register of Historic Places in August 2019 yet keeps trading hands.

Six years before his death in 2018, Portland urban planner John Fregonese pitched the City Council on converting the building into a transit-oriented development. A nonprofit then hoped to turn it into a community center. Then it sold in a sheriff’s auction to an architect who hoped to turn it into an arts, office and events venue. Just a decade ago it was among The News’ 10 Drops in the Bucket, those ever-present eyesores and nuisance properties allowed to fester everywhere except, of course, in North Dallas.

From 2015 until early 2020, Michael Swiercinsky of Rockwall owned the Bilal Building in the hopes of turning it into artists’ lofts and offices. “I love historical buildings,” he told me Tuesday, “and it was a very good buy. But with the rents, the construction costs and that market, it just wouldn’t work, so we put it on the market.”

The for-sale sign in front of the Lee G. Bilal Building is several owners old by now.

Robert Wilonsky

It sold quickly, he said — and for cash — to an LLC called Second 55 Venture, which tied back to a box at a UPS store on Cedar Springs Road. The LLC, which last year sold some land to the city for the Cadillac Levee, was represented by attorney Garreth Sarosi, who told me on Monday that at one point, “the Navy wanted to use [the Bilal Building] for the SEAL team to practice in — I am not kidding.”

He wasn’t sure why his clients bought the building. But he has a good idea why they sold it: “Dallas is sort of running out of space — core Dallas, I mean — and at some point this neighborhood is going to boom, because there’s a lot of stuff there and a lot of space to develop. But so far, there hasn’t been a first mover.”

Sarosi helped his clients sell the property two years ago to Arpeggiate LLC, whose principal address is — once again — a box in a UPS store in Preston Center and whose registered agent is a company in Austin called Texas Registered Agent, which allows business owners to keep their identities secret for $35 a year. A little digging turned up a contact: an office on Maple Avenue belonging to longtime tax attorney William E. Johnson III.

The untended-to Lagow Cemetery sits behind the Bilal Building. This is the grave of Tennessee native Franklin H. Harris, a member of the Woodmen of the World fraternal organization. In the distance you can see an opened window in the Bilal Building.

Robert Wilonsky

Johnson wouldn’t tell me who his client is, only that he’s the billionaire who doesn’t believe in banks and who’d rather deposit his money in real estate. He said his client probably has no idea the Bilal Building is on the National Register.

I asked if his client lives in Dallas. “Yes.” I asked if it’s someone whose name I would know. “No,” Johnson said. “No one knows his name and no one will know his name.”

I asked if his client had any plans for the building. “No.” But he said he would ask.

That was Tuesday. Nothing since. I’ve got nothing but time; the Bilal Building I’m not so sure about.