A century after the Surrealist Manifesto drew attention to the unconscious mind as a subject and source for visual art, “International Surrealism,” a new exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art, showcases more than 100 artworks from the collection of Tate in London, with particular attention to the way the movement was adopted in far-flung places.

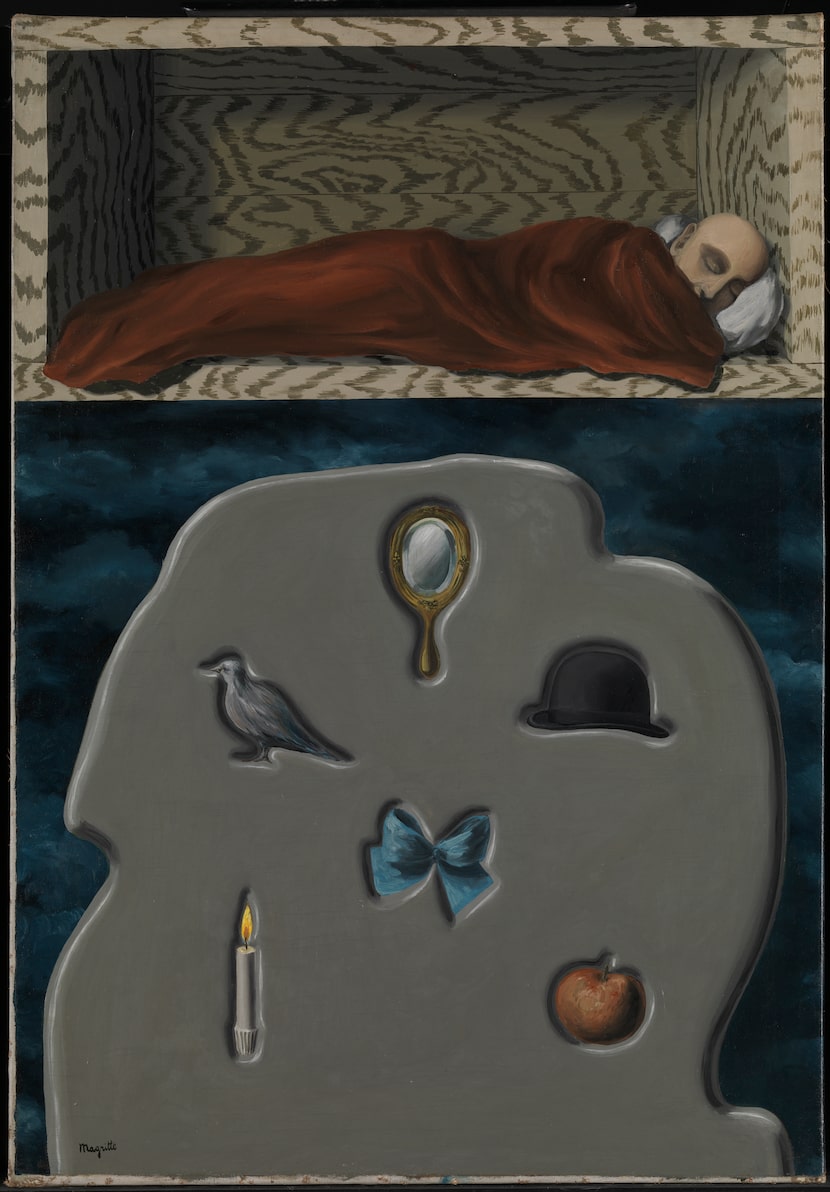

As adopted by surrealist artists, Sigmund Freud’s psychological theories proposed to liberate the mind from the dictates of reason, finding inspiration in (superficially irrational) dreams, and in the method of automatism, which involves giving up conscious control while writing or drawing. Following this approach, in paintings by Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Max Ernst and Leonora Carrington, the symbolic and narrative logic remains just out of reach of decipherment, much as a dream might remain puzzling for some time after waking up.

The DMA’s show demonstrates the remarkably broad and long-lasting appeal of surrealism to artists on several continents, both in its own right and as a seedbed for other, later art movements. Why did the movement get so big? One possibility is that surrealist ideas were expansive enough for the movement to embrace quasi-surrealist artists such as Joan Miró and Giorgio de Chirico, who largely pursued their own agendas, despite sharing affinities with the mainstream of the movement.

“Autumnal Cannibalism” is a 1936 painting by Salvador Dalí, one of the leading artists in the Surrealist movement.

Marcus Leith / Tate

News Roundups

“Fire! Fire!,” completed in the early 1960s by Enrico Baj, features a character that wouldn’t seem out of place on a modern fractured fairy tale on the Cartoon Network.

Lucy Dawkins / Tate

Another possibility is that surrealism’s bizarre dream imagery filled a void: After the 19th-century trend toward disenchanted realism had stripped out much of the mythical and imaginative content present in earlier art (from Greek myths to folk tales and fairy stories), audiences were hungry for magical visions of another world. Works such as Enrico Baj’s Fire! Fire!, whose figure looks like a character from a modern fractured fairy tale on the Cartoon Network, offer an imaginative escape.

Yet another possibility has to do with the widespread appeal of surrealism’s core value of liberating the self from external constraints, manifested in the movement’s affinity for revolutionary politics and sexual libertinism. Surrealists, in other words, would be perfectly at home in contemporary progressive culture, which follows the same logic.

One might object that this latter agenda entails certain drawbacks, as when political revolution leads to dictatorship, or the liberation of the male sex drive ushers in the objectification and exploitation of women (both of which are touched on in the present show). But the intrinsic appeal of liberation remains strong, especially in how the movement’s devotees tend to ignore or pass lightly over such concerns.

That aside, the strengths of “International Surrealism” are many. The medium of photography is particularly well-suited for the surrealist interest in capturing surprising and incongruous juxtapositions, both in the form of collage, and in how urban strolls can bring forth chance encounters; the photographs here by Eileen Agar, Bill Brandt and Paul Nash are a highlight.

The international aspect of the show is also enlightening, although it perhaps could have been more so. Before visiting, I slightly feared “International” might mean only “Western Europe and the United States,” and it largely means that. But the works by Krishna Reddy of India and Aubrey Williams of Guyana were remarkable and left me wanting to see much more.

“Variation on the Form of an Anchor,” a 1939 painting by Tristram Hillier, is drawn from the Tate’s deep collection of works by British artists who are not much seen or known in this country.

Estate of Tristram Hillier / Tate

Works by Wifredo Lam, a Cuban artist of African and Chinese ancestry, such as his Ibaye, on view here, show surrealism’s affinity for the cultural hybridity of the Americas. Also notable is the Tate’s deep collection of works by British artists, such as Tristram Hillier and F.E. McWilliam, who are not much seen or known in this country.

Both implicitly and explicitly, viewers can see how much later movements owed to surrealism. Included here are great examples of work by abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, making clear how much their lines owed to the automatic drawing of surrealists such as André Masson and Henri Michaux (both included). Seen side-by-side with Yves Tanguy’s depictions of undulating shapes floating in imaginary space, the lineage from surrealism to abstract expressionism is apparent.

Artist-led protest against Trump administration comes to Dallas

Artist-led protest against Trump administration comes to Dallas

North Texas groups are participating in Fall of Freedom, which organizers have described as a “creative resistance.”

15th-century Bible called the ‘Mona Lisa of illuminated manuscripts’ on display in Rome

15th-century Bible called the ‘Mona Lisa of illuminated manuscripts’ on display in Rome

The two-volume Borso D’Este Bible is known for its opulent miniature paintings in gold and Afghan lapis lazuli.

Likewise, those familiar with the world-class collection of post-1945 Japanese and Korean art at the Warehouse in Dallas, or the soft sculptures of Louise Bourgeois and Yayoi Kusama, will be able to draw connections from those to many of the works on view at the DMA, such as Dorothea Tanning’s Pincushion to Serve as Fetish.

As much as any 20th-century art movement, surrealism embodies the paradox that, when a revolutionary avant-garde becomes part of history, institutionalized in museums, it must then find sources of appeal beyond the revolutionary frissons that once drew adherents to it in its youth. Although surrealism’s political and sexual radicalism ruffled plenty of feathers during its heyday, from the vantage of a century later, what stands out most are its continuities with, rather than its radical breaks from, the broad sweep of art history.

René Magritte’s 1928 painting “The Reckless Sleeper” is among the highlights of the “International Surrealism” exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art.

Sam Drake / Tate

Details

“International Surrealism” is on view through March 22 at the Dallas Museum of Art, 1717 N. Harwood St. Open Wednesday through Sunday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. $21.50 for adults, $19.50 for seniors and military, $17.50 for students, and free for members and children under 11. Call 214-922-1200 or visit dma.org.