The 379th Criminal District Court in San Antonio was bulging with people last Friday, so filled with journalists, police, attorneys, and staff that bailiffs shooed those without a seat out the door.

People wanted to see, first-hand, the unprecedented trial that was set to begin.

Before the judge called the room to order, Bexar County Assistant District Attorney Darly Harris leaned over the bannister separating the gallery from the prosecutors’ table. He brought his face level with that of the young woman seated there. He quietly appeared to tell her what was coming up, and he reminded her about the gaggle of press just a few aisles behind her.

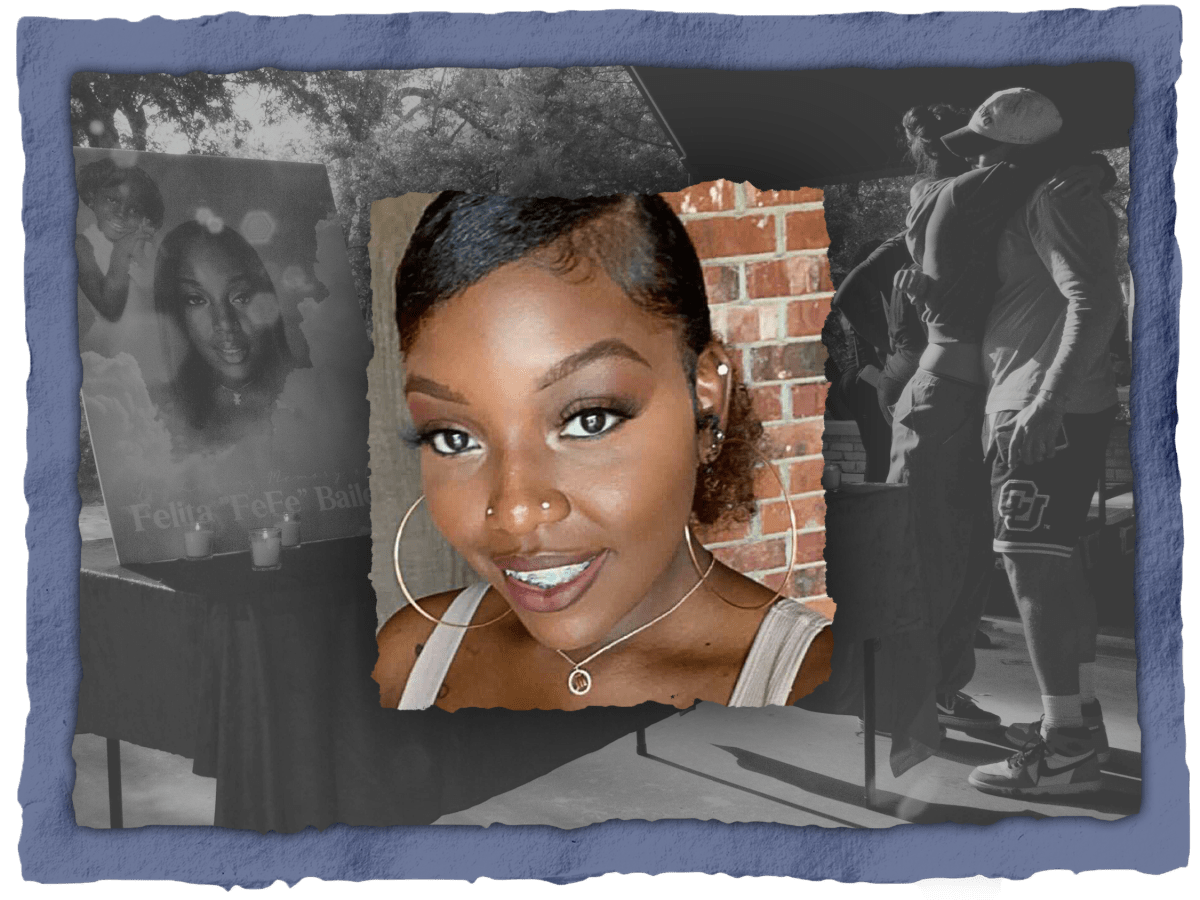

While outwardly calm, Alexis Tovar, 26, had been nervous about the morning’s events for two years.

“I’m on high alert all the time waiting for this trial. So mentally, it’s exhausting,” Tovar told The Barbed Wire a few days prior.

Before long, Tovar was wiping her eyes with a tissue as attorneys gave their opening statements. The prosecution’s and defense’s arguments charted different realities of what led to the death of Tovar’s mother, Melissa Perez.

The prosecution, through Harris, made the case that over the course of two and a half hours, San Antonio police officers escalated a once-calm situation and murdered Perez. Defense attorneys for those officers argued the unstable woman repeatedly threatened the police, nearly striking them with a deadly weapon.

Perez was killed in the early hours of June 23, 2023 — one of 22 people shot by San Antonio Police that year, according to reporting from KSAT.

Unlike the other shooting cases that year, in which 14 people died, Perez’s case resulted in the suspension of San Antonio Police officers. Days later, they were arrested for her murder.

The murder charges were unheard of. Never in the history of San Antonio, the seventh largest city in the country, has an officer been charged with murder for an on-the-job shooting.

No charges were filed against SAPD Sgt. David Perry when he shot Hannah Westall in a shopping center parking lot on March 20, 2019. The 95-lb woman had a BB gun shaped like an UZI submachine gun shoved into the back of her pants. Dash camera footage showed that Perry shot her within 15 seconds, though Westall never pointed the weapon at the officer, and told him it was fake, according to court documents from Tovar’s lawsuit.

John Montez was shot twice in the chest while holding a knife in his kitchen. His wife had called the police, worried the combat veteran who was suffering from mental health problems might hurt himself. Police say he lunged at them, but court documents from Tovar’s lawsuit allege his family saw body camera footage showing no lunge on that fateful March day in 2021.

Both shootings were investigated, and police in Montez’s death were brought before a grand jury, but neither resulted in charges, both qualifying as a genuine threat to the officers lives.

Perez’s case stretched the definition of “credible threat.” Can a woman in her own apartment behind a locked glass patio door with a blunt object really be a threat to police officers?

According to experts at the Police Integrity Research Group and Bowling Green University, police are hardly ever prosecuted for bad shootings. Their analysis of 15 years of data between 2005-2019 found only 2% of police were charged with murder in fatal encounters nationwide.

“Few officers are convicted because juries and courts are reluctant to second-guess split-second life-or-death decisions of police officers in potentially violent street encounters,” the study’s authors wrote.

A Life Cut Short

Melissa Perez grew up in San Antonio. She had Tovar, her oldest of four children, when she was 18.

The family moved from apartment to apartment, Tovar said. They didn’t have much but her mother was quick to give to others. Perez was a good cook and anything Tovar mentioned wanting her mother would make the next day.

“There will be times where she would go work on a roof as a roofer to feed us, get us school clothes,” she said.

Still, Perez struggled with her mental health. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia in her 40s.

Defense attorneys hinted at another, darker version of reality in their opening statements. They said evidence from Child Protective Services would show the woman’s “psychosis” had impacted her for decades and that all four of children were removed from her home.

Child Protective Services was a part of the family’s life, Tovar said, but declined to elaborate, adding only that Perez was never violent and she and her brothers are proof of her ability to parent.

“We are all four of us pretty great kids,” she said, rattling off academic and extracurricular accolades for her brothers. Dylan, 11, has straight A’s and is also a solid clarinet player, she said. Jayden, 17, is in all Advanced Placement courses as a sophomore. Aiden, 18, is an accomplished football player.

In the years before her death, Perez’s behavior grew more erratic. None of her children lived with her anymore. Jayden and Aiden lived with their father and her youngest, Dylan, lived with Tovar.

In 2021, Perez was hospitalized for schizophrenia and placed on powerful drugs to help her navigate the condition. She moved in with Tovar after being discharged, and for months she shared a room with her grandson.

Perez held down a job working from Tovar’s home as a customer service representative in the medical field. She seemed to be doing well, her daughter said. That’s when she wanted to get her own place. Tovar was skeptical, but she said her mother was excited when she moved into Rosemont at Miller’s Pond Apartments, a public housing complex on San Antonio’s southwest side.

Perez did well for a while. But Tovar believes that without her and her husband’s help, her mother wavered with her medication.

Eight months after moving in, Perez was found cutting wires to the exterior fire alarm at the apartment complex. The tampering triggered the alarm causing her building to evacuate. Multiple neighbors called 911. Recordings played in court heard one exasperated neighbor complain that a woman (Perez) admitted to it and said she owned the building.

The San Antonio Fire Department sent a unit to respond.

Police body camera footage shows Perez telling fire and rescue personnel that the FBI was using the fire alarm equipment to surveil her. A toxicology report would later show she was intoxicated.

The initial police response was limited. Two officers — Jesus Rojas and Robert Ramos — arrived in separate cars. After speaking briefly with Perez, Rojas attempted to get her to come to his car to speak more. As he walked in front of her towards the patrol car, body camera footage shows she fled to her apartment.

Another unit arrived and the three officers attempted to talk her out of her apartment, body camera footage would show.

Prosecutors said Perez refused. In his opening arguments, Harris said that at that point, 48 minutes had passed, and that the officers were told by detectives downtown that they could write up the incident and leave. Someone would follow up at another time.

But when the apartment maintenance man told the officers the estimated damage was several thousand dollars, a felony amount, the officers decided to try to arrest Perez again, Harris said.

They knocked and kicked on the door for the next 30 minutes.

At one point an officer tore the screen on an open window and attempted to unlock the patio door, according to body camera footage and court testimony. Perez picked up a hammer and ran at the officer, swinging it and striking the window frame. She then threw a vigil candle out the window striking the officer, who called for additional units.

Another dozen San Antonio police officers showed up, including the accused Sgt. Alfred Flores, Ofc. Nathaniel Villalobos, and Ofc. Eleazar Alejandro.

According to prosecutors, Flores, the ranking officer on the scene, rejected plans to breach the home in a way that would allow for a less lethal response. Defense attorneys would argue Flores and the other officers weren’t notified that they were responding to a mental health case.

Body camera footage showed that Flores said they must enter because a second person was in the home. Given the mental state Perez was in and the fact that she had threatened officers with a hammer — they felt the man may be at risk. The man was a known transient, according to the San Antonio Fire Department, whom Perez had taken in.

After two and a half hours, Flores and Villalobos again tried to get in the apartment through the patio door, while Alejandro spoke to the woman through the open window.

During the final attempt, Perez was shot while wielding a hammer and, police said, rushing the three men. They fired through the closed — and locked — glass patio door.

‘I Didn’t Get to Say Bye’

Within hours, the San Antonio mayor, the city council, mental health professionals, and the Chief of Police condemned the shooting.

Flores, Alejandro, and Villalobos were suspended and, days later, arrested for murder. The charges against Villalobos were later reduced to aggravated assault with a deadly weapon because the bullets from his gun did not strike Perez.

Defense attorneys have repeatedly attacked the investigation, saying police filed murder charges within a day, calling it the result of pressure from senior police leadership and the public rather than police work.

The family filed a wrongful death lawsuit two weeks after the shooting against the three officers, the police department and the city of San Antonio.

It alleged, among other things, that SAPD fostered a culture of excessive force, maintained poor oversight and training and questioned policy and practices of its Mental Health unit — which it argued was severely limited at night.

But the civil rights lawsuit was thrown out last month.

“Given all these circumstances, the presence of a glass door between Perez and the Officer Defendants does not make the use of deadly force excessive,” wrote U.S. Magistrate Judge Henry Bemporad in his recommendation, echoing hundreds of judgments of officer-involved shootings past.

Tovar disagreed that her 130-pound mother posed a threat to three, physically fit policemen behind a glass door.

“I don’t know how you watch that (body camera footage), and someone could say something like that, because I feel like the video speaks for itself,” Tovar said.

She didn’t tell her youngest brother, Dylan, who lives with her, about the civil court ruling. The 11-year-old has taken things hard in the past.

“I don’t update him too much. It does affect him a lot,” said Tovar.

Her mother’s death affected her profoundly as well. The oft-bubbly and optimistic woman was waylaid by depression that made it difficult to get out of bed in the months that followed her mother’s shooting.

“I feel robbed because I didn’t get to say bye. I didn’t get to hug her. Talk to her one last time,” she said.

Caring for her own two children and helping her brothers while finishing a nursing program meant she had to ask for help. She credits therapy, running, and her faith for keeping her on track after losing the woman she has called her best friend.

Tovar finished her nursing program, though with a slight change in focus. Initially, she hoped to work in mental health, so she could help her mother. In the aftermath of Perez’s violent death, her studies brought back too much of the pain. She is scheduled to start working as a labor and delivery nurse later this month.

‘Burn It Down’

In the two years since the shooting, the case has been delayed by motions alleging prosecutorial and judicial impropriety filed by a high-profile defense team boasting several former prosecutors, including former Bexar County District Attorney Nico LaHood.

The case was originally set for trial late last year, but was removed from the 187th District Court after the defense team successfully argued Judge Stephanie Boyd showed bias against their clients.

The trial of the three men is expected to last through the week, and Tovar has said she will be there as much as she can.

“I feel like these are gonna be some of the hardest days that are coming,” Tovar said.

The defense team has been largely silent in the media, so opening arguments presented the first public defense of the three officers’ actions.

Jason Goss, one of Villalobos’ attorneys, argued the officers had a right to make it home safely that night and Perez’s actions were a threat. He said that leaving without arresting her would have left other people at risk.

“You can’t destroy the fire alarm at the apartments, endangering hundreds of lives…run away from the detention and make it home and you’re safe,” he said. “That’s not how it works.”

What happens next depends on days of testimony, the arguments of more than ten attorneys, and ultimately a decision reached by 12 Bexar County residents.

If the prosecution is victorious, the criminal trial could result in the unusual situation rendering criminal liability in a case that a civil court, with a lower threshold, found spurious. The family is waiting to see what happens in the criminal trial before they decide whether to appeal in civil court.

“Accountability?” Tovar responded to a question about what result she wants. “I just need something — some sort of change, some sort of awareness.”

A historic murder conviction would again shine a spotlight on when police respond to mental health calls — and, very likely, years more of trials and appeals from this tragedy.

For the defense, the case amounts to order versus chaos. If the jury finds his clients guilty, Goss said it would upend how police are able to make basic arrests, leading to chaos.

“Just wait and see what kind of community we live in, if we convict these men of murder and aggravated assault,” Goss said. “Burn it down.”

Related