Understanding climate change and natural disasters helps cities better navigate lingering challenges such as the effects of flooding or the risks of earthquake-prone areas, researchers say.

That’s why professors from across disciplines at the University of Arlington at Texas are crisscrossing the state and country to the South Texas Gulf Coast and as far as California to study air samples, changing fault lines and more.

Just this fall, for example, a UTA team took their data and research to the inaugural Smart Coast Summit in Corpus Christi, where community leaders, policymakers and experts from around the world gathered to discuss emergency management, environmental policy and other related topics.

Michelle Hummel, associate professor of civil engineering, and Oswald Jenewein, associate professor of architecture, are at the forefront of collecting data from the Texas Gulf Coast.

They combine technology, urban planning and public policy to better understand the effects of flooding, declining air and water quality, and industrialization on Corpus Christi Bay residents and communities.

Thanks to $2.5 million in federal and state funding, over 150 UTA students have traveled to the Corpus Christi area under the university’s Smart Coast Initiative, an interdisciplinary project focusing on developing solutions for coastal communities impacted by environmental issues.

A network of sensors along the coast and in the bay provides the students and professors with information about the region’s particulate matter levels, stemming from vehicle emissions and gas-powered seacraft. Particulate matter, also called particle pollution, consists of microscopic solids or liquid droplets that can be inhaled.

Corpus Christi “is understudied when it comes to larger environmental studies,” Jenewein said.

The South Texas coast’s air and water quality have increasingly worsened due to torrential storms, hurricanes and industrialization, mainly the region’s growing oil and gas industry, according to reports.

University of Texas at Arlington associate professors Michelle Hummel and Oswald Jenewein speak with students and community members in Ingleside, bordering the Corpus Christi Bay area. (Courtesy photo | University of Texas at Arlington)

University of Texas at Arlington associate professors Michelle Hummel and Oswald Jenewein speak with students and community members in Ingleside, bordering the Corpus Christi Bay area. (Courtesy photo | University of Texas at Arlington)

The monitors identify which volatile organic compounds, also known as VOCs, are present in the area. VOCs come from human-made chemicals commonly found in paints, cleaning supplies, cosmetic products and manufacturing plants.

Exposure to these pollutants can lead to health conditions including aggravated asthma, impaired lung function, fatigue and dizziness, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

High levels of the VOCs or particulate matter can worsen existing conditions such as respiratory and heart disease.

“People are concerned about what’s happening miles away from those monitoring sites,” Hummel said. “In some cases, people are living right along the fence lines of these industries, so not really knowing what is in the air is a major concern.”

As for the coastal area’s water quality, professors are collecting data on flooding, rising sea levels and erosion to determine how they affect homes, roadways and other infrastructure.

The Smart Coast Initiative helps communities understand the quality of their recreational and drinking water supplies amid Corpus Christi’s looming threat of running out of water, Hummel said. Resource-hungry industrialization is contributing to that threat.

“It affects the residents, understanding how these changes are going to influence their quality of life and their well-being,” she added.

Storms, flooding and other natural disasters can affect a water source’s depth, salinity, turbidity and oxygen levels, Hummel said. While those factors are large determinants of Corpus Christi Bay’s ecological makeup, they also influence how the public uses the water.

Students visit the sensors installed by the Smart Coast Initiative in Ingleside, collecting data on water and air quality. (Courtesy photo | University of Texas at Arlington)

Students visit the sensors installed by the Smart Coast Initiative in Ingleside, collecting data on water and air quality. (Courtesy photo | University of Texas at Arlington)

Hummel, Jenewein and their colleagues plan to continue bringing researchers and experts together to develop the Coastal Bend Vision 2050, a long-term plan to address the area’s biggest environmental challenges.

The ultimate goal for Hummel, Jenewein and their colleagues is to develop a dashboard of data that informs decision-makers and residents.

“When that is all up and ready for the public, it will go a long way with policy recommendations that we make,” Jenewein said.

Geological history below California’s crust

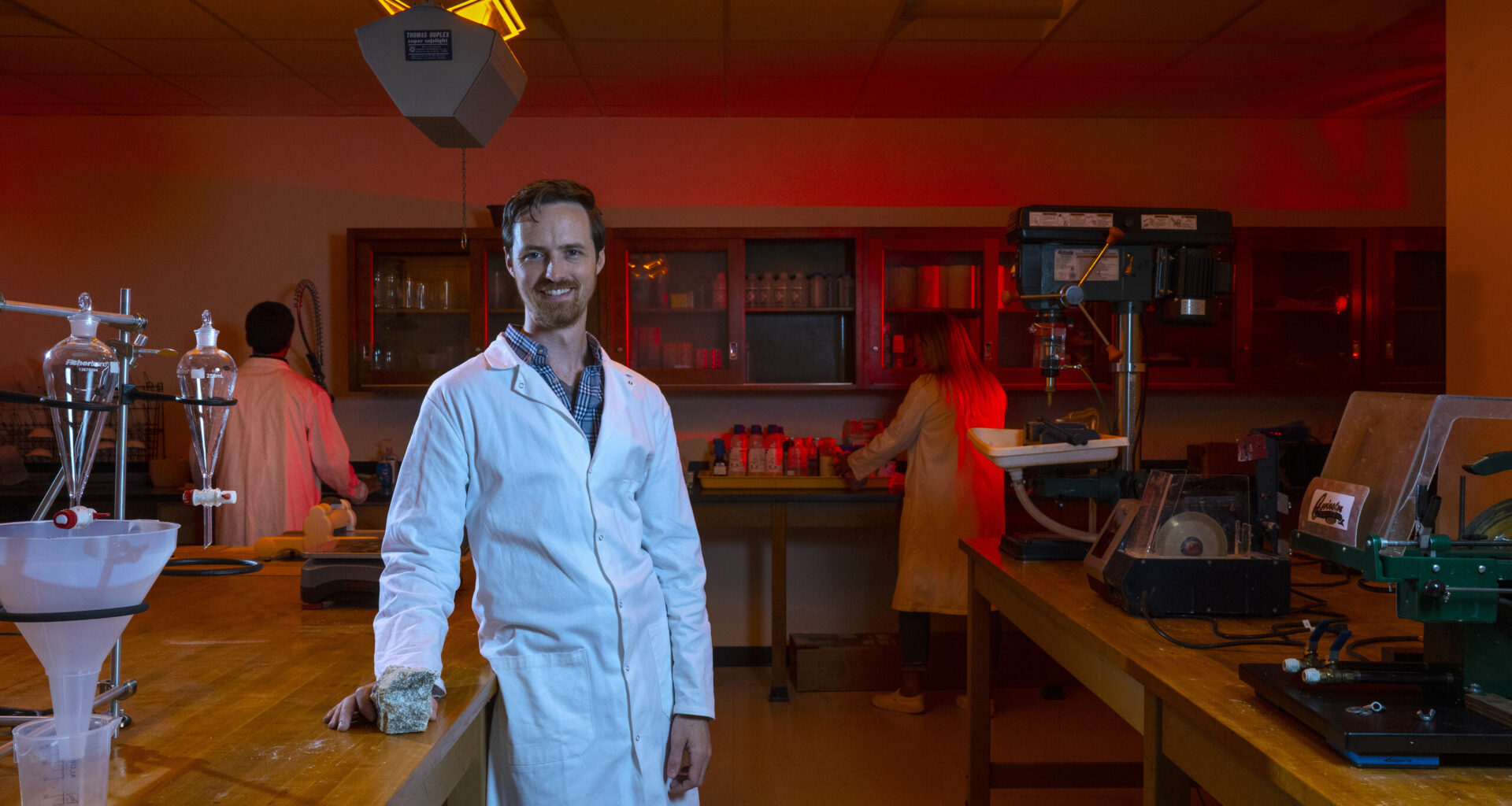

UTA’s reach stretches to California as its Dark Lab pressurizes and breaks apart rocks.

Nathan Brown, an assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences, oversees a team of students helping experts identify which segments of the San Andreas Fault remain active, posing the most risk for a natural hazard.

Describing some of the research process as a “hike,” Brown and his students have visited different landscapes throughout the country, such as the San Gorgonio Pass in Southern California, where they collect samples of bedrock along fault lines.

They determine how the area’s landscape has evolved by identifying the specimen’s seismic hazard — or thermal history — and erosion.

Highly eroded and elevated landscapes are a tell-tale sign of active faults, Brown said.

“When you do that enough times, you can tell a story through time of which parts in the landscape are eroding down, which ones are steady and not eroding very much,” he said. “That, in turn, tells us about fault activity.”

This past spring, Brown and his student Ayush Joshi collected samples from the San Gorgonio Pass, a segment of the San Andreas Fault. An earthquake-prone region, the San Andreas Fault is an 800-mile fracture in the earth’s crust where two major tectonic plates, the North American and Pacific plates, meet.

A California native, Brown long researched the San Andreas Fault before he found himself at UTA in 2020.

With the need for more examination on the various segments of the fault, Brown secured funding from the Statewide California Earthquake Center, a research and education hub.

“The (San Andreas Fault) is actually super fractured,” Brown said. “Piecing apart which of these fault strands hosts big earthquakes, which are not posing any active hazard is one of the main jobs for geologists when they’re working in an area like that.”

Joshi presented the team’s findings at the center’s annual meeting in September. The event brings experts together to advance education on earthquakes and how they impact communities inside and outside of the state.

Brown will present a summary of their research to the state organization by February.

It’s his hope that through the earthquake center collaboration, he and other scientists — along with urban planners — can help shape development and public policy that minimizes the risk to public safety.

“That’s the dream,” Brown said. “I hope that we can … figure out a safe way to build up our cities that works well for everyone, that doesn’t put anyone in undue risk.”

Nicole Lopez is the environment reporter for the Fort Worth Report. Contact her at nicole.lopez@fortworthreport.org.

At the Fort Worth Report, news decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.

Related

Fort Worth Report is certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative for adhering to standards for ethical journalism.

Republish This Story

Republishing is free for noncommercial entities. Commercial entities are prohibited without a licensing agreement. Contact us for details.