I pulled up to the intersection of Eugene and Myrtle streets a little past 1 in the afternoon Saturday, where dozens of folks — old men, young women, little kids — were gathered near the orange Myrtle Super Deli convenience store on the corner. It’s like this on most nice afternoons, an impromptu block party just off Malcolm X Boulevard, boisterous and friendly.

At the corner, parked in front of a battered blue house with a crumbling roof where an icon and genius once lived, was a van with its door slid open. I parked a few feet away, along Eugene. A woman, who would later identify herself as Bronsha McDonald, said to her friends and young son, “Maybe that man’s coming to buy Ray Charles’ house.”

Charles lived at the intersection in the mid-1950s while assembling his crack Atlantic Records band, featuring Lincoln High School graduate David “Fathead” Newman on sax, and writing hit singles that will survive until the sun grows cold. We know the address because Charles put it in his autobiography: 2642 Eugene.

Today, it looks like any other old rent house left to rot on a South Dallas street corner.

Most people in this town have no idea Charles ever lived in Dallas, much less assembled the band that became “among the most influential musical units in the history of pop, rock, soul — whatever you name it,” as David Ritz wrote in the liner notes of the 1997 boxed set Ray Charles: Genius & Soul. There’s no sign out front saying Ray Charles used to reside in this house with his second wife, Della Beatrice Howard, and the first of their three sons, Ray Jr., both of whom Charles often abandoned for long stretches while touring.

Opinion

In the summer of 1973, during a lengthy engagement at the late Western Palace on Skillman Street, Charles told the Dallas Times Herald, “I was gone so much on the road I had to remember that address to give to people.” Five years later, in his autobiography Brother Ray, co-written with Thomas Jefferson High School graduate Ritz, Charles called it “our little house on 2642 Eugene Street,” where his wife often waited and worried, “I’m certain, and the hurt must have been painful and long-lasting.”

In a town where nothing’s sacred, where South Dallas landmarks are threatened by city attorneys and one of its most expensive and iconic buildings is at risk of being tossed in the landfill on behalf of a Vegas gambling family, it should come as no surprise there’s never been any effort to protect or celebrate this significant footnote in American musical history. Nothing beyond the occasional newspaper story remembering its past and lamenting its likely future.

I’ve driven by the house several times in recent months and noticed only that it looks worse with each visit. I stopped Saturday only because I’d seen mention of a Ray Charles collection released just the day before, consisting of early 1960s singles and outtakes, and it felt like as good a time as any to pay respects.

The rear of 2642 Eugene St., with its collapsing roof and detached back wall

Robert Wilonsky

“I think it’s horrible they’ve done nothing to save that house,” Ritz told me last week. “Ray lived in Dallas at a critical time in his life, when his music was changing — when he was innovating gospel and rhythm and blues and putting his small band together and getting his chops down. It’s not only a blatant disregard of a vital moment in the history of American musical culture, but it should be a big deal in Dallas. This drives me crazy.”

I’m never sure how long the house has left — like, one day I might turn onto Eugene off Malcolm X and it’ll be gone. That’s just how it works in this town. A few years back it looked like it might become a museum. Today it looks like it might collapse in on itself.

The roof, nearly worn through in large stretches out front, has nearly collapsed in the back, where an exterior wall is being held in place by pieces of wood propped up by cinder blocks. Through the collapsed exterior you can see the inside of the house, where a thick layer of dead leaves covers what used to be the floor.

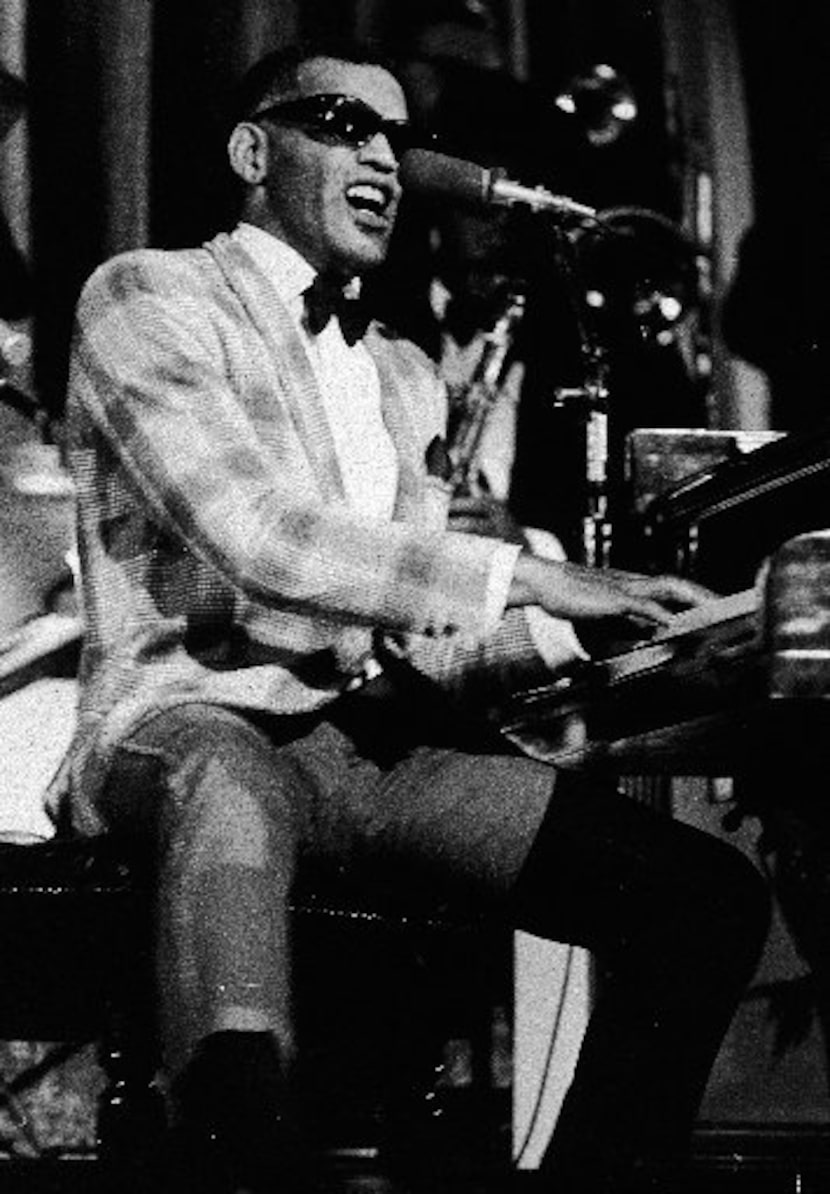

Ray Charles, around the time he lived in South Dallas

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

I was standing in the back with D.J. Smith-Rhodes, a 26-year-old Lincoln grad I met Saturday in the convenience store across from the house. He was wearing a Prince T-shirt and told me he was a rapper, then asked if I wanted to see his new video, which was shot almost entirely in front of 2642 Eugene.

He peered through the wall and shrugged, unsurprised that the house had fallen into disrepair. “That’s just a thing you expect,” he said.

I took pictures Saturday and texted them to Ritz, who responded, “Painful to see those photos.” He suggested I call Valerie Ervin, head of the Ray Charles Foundation, to see if they’d ever inquired about the house, but she didn’t respond.

The 34-year-old McDonald told me her grandmother used to live across the street. She and other neighbors hanging out at the corner Saturday still call it “Ray Charles’ house.” Everyone in this Queen City neighborhood knows someone or is related to someone who remembers when Charles lived here.

Now, though, “it’s just there,” McDonald said, shrugging toward the house where the only residents are the feral cats that come and go. Folks with whom I spent time Saturday said they rarely see someone on the property. Maybe when the grass gets mowed.

A peek inside 2642 Eugene St., where the back gate was open and the yard was full of trash

Robert Wilonsky

“They should make it into a landmark,” said McDonald, without any prompting, hand to God. “A museum.”

That’s just what the house’s current owner, Mark Ellis, told me he hoped to do with 2642 Eugene shortly after he bought, repainted and sealed up the house about seven years ago. At the time, Ellis told me he had no idea the house had once served as the Dallas residence of the man who reinvented rhythm and blues, reinvented country and reshaped pop.

“After I realized it was Ray Charles’ house, I wanted to reserve it for some special treatment,” Ellis told me. “I haven’t figured out what I want to do.”

I guess he still hasn’t figured that out. I’ve tried to reach Ellis in recent days to ask about the house’s shabby shape, but he hasn’t responded to messages and emails.

In Brother Ray, Charles told Ritz he hated his wife’s hometown of Houston for a number of reasons (among them, “it always seemed wet and muggy”). So in 1954, before they were married, he moved them to Dallas because he already had friends here, including a couple of cab drivers and alto sax player Buster Smith, who’d played with Count Basie and mentored Charlie Parker. Said Charles, “I knew the town and I dug it.”

He’d played here often, too, usually at the Empire Ballroom on Hall Street. For a time, he even lived behind the Empire in the Green Acre Courts on McCoy Street, one of the few motels in this town where Blacks were allowed in the early 1950s. Its ruins were dismantled and dumped in 2017.

The American Woodmen Center is but a few blocks from Ray Charles’ 1950s home on Eugene Street. Here, David “Fathead” Newman, a graduate of nearby Lincoln High School, and other jazz greats performed for decades. Its current owner is considering selling the place within a year, after which point he wonders what will become of the Woodmen if it’s not landmarked.

Robert Wilonsky

Charles might have been drawn to the house on Eugene because of its proximity to the American Woodmen Association Center, a fraternal hall that opened in the mid-1950s on Carpenter Avenue just a few blocks away. On Sunday nights, jazzers held court at the Woodmen, including pianist Red Garland, who’d played with John Coltrane, and David Newman, Leroy Cooper and James Clay, sax players who’d come from Lincoln High School and wound up in Charles’ bands over the years, with Cooper serving as Charles’ musical director for decades.

Newman, the man famously called Fathead, had actually met Charles in 1951, when Ray was on the road with Lowell Fulson and the sax player was touring with Buster Smith and Oak Cliff’s own T-Bone Walker, whose guitar electrified the blues. Three years later, Newman was playing on Charles’ R&B-chart-topping single “I’ve Got a Woman”; in 1959 came another immortal, “What’d I Say.” Charles told the Times Herald both were written during those days in Dallas.

In between, Newman released his solo debut in 1958, Fathead: Ray Charles Presents David Newman, which featured his boss on piano. For years after its release, Newman would occasionally show up at the Woodmen hall to play its most famous song, “Hard Times.”

The Woodmen hall still stands, though Rickey Ferguson, the 71-year-old who has owned it since 1979, told me this week he’s been considering selling the venue he occasionally still rents for parties and neighborhood gatherings. I asked him if anyone had ever approached him about landmarking the building, given its role in Dallas music history. Of course not.

D.J. Smith-Rhodes stands in front of Ray Charles’ former house on Eugene Street, where he recently filmed a music video.

Robert Wilonsky

“I am kind of looking at what I am going to do with the building in the next year or two,” Ferguson said. “I would like to do what’s best for the neighborhood. I am willing to do something that will help the neighborhood and preserve the history of the building.”

That’s a conversation we’ll likely need sooner than later.

Ritz would like to see Charles’ house turned into a museum and cultural center, like the Louis Armstrong House Museum in Queens, N.Y., where music plays while visitors look at old photos and the trumpeter’s artifacts. The neighborhood, too, has all kinds of ideas for Charles’ house. A few folks pointed to the city-owned Juanita J. Craft Civil Rights House less than a mile away on Warren Avenue and said, look, just do that.

If nothing else, Smith-Rhodes said, “it needs a sign — not just his name, but his face, a picture of Ray Charles. A real monument. It would be special for our neighborhood.”

I asked Smith-Rhodes whether it should be a museum. He paused. Then he smiled.

“But it is a museum,” he said. “That’s just how our museums look over here.”