Of all the irresponsible, ill-conceived, short-sighted, counter-productive, cynical, philistine and downright dumb ideas I’ve heard in my time writing about Dallas, the prospect of razing City Hall stands alone. Demolishing architect I.M. Pei’s iconic building would be an act of epic mismanagement indefensible on aesthetic, environmental, financial or moral grounds.

And yet, next week the City Council will begin deliberations on the future of City Hall, the ostensible justification being a deferred maintenance bill likely to exceed $100 million. That cost has exposed the building to critics who say it is ugly (a matter of taste) and dysfunctional (blame decades of neglect and underfunded maintenance) and to those who would love to get their hands on its prime downtown real estate.

The pending redevelopment of the convention center, which will open up a swath of adjacent land, has made the City Hall site especially appealing as a potential spot for a new basketball arena for the Dallas Mavericks, a prospect that has downtown’s developer class rubbing their collective hands in anticipation.

There is a word for this: boondoggle. Dallas taxpayers would be paying an enormous premium — and giving up their majestic, centrally located seat of government — for the benefit of real estate interests, the building industry and the billionaire owners of the basketball team that shipped the city’s favorite son out of town in the middle of the night and then raised ticket prices.

News Roundups

While the price to repair City Hall may be large, it is dwarfed by the potential cost of a new building. Willis Winters, the broadly respected architect and former director of the city’s Park and Recreation Department, has estimated the expense of replacement at $825 million, and that’s not including the enormous costs (both financial and environmental) of demolishing a titanic work of poured-in-place concrete, a project that would cover downtown in dust for ages.

If the Mavs want a new arena downtown, there are numerous other potential locations, including land already being opened up by the reorientation of the convention center. (The city has yet to present a compelling vision for what will occupy this space even as it spends billions on the project.) Whatever the location, the Mavs should pay for their arena themselves, without a penny of public money.

Aerial view of I. M. Pei’s City Hall and plaza under construction in 1976.

TOM DILLARD/Staff Photographer / dallas Morning News

Why Dallas can’t have nice things

There is something sadly familiar about this story. Like a spoiled child who leaves toys out in the rain, Dallas refuses to take care of its most precious objects — Fair Park, the Kalita Humphreys Theater, the buildings of the Arts District — leading to staggering costs for repair and questions about whether those landmarks are worth saving. This correlates with another Dallas tradition: the treatment of its built history as disposable. Dallas always seems willing to wipe away its past when moneyed interests come calling.

The striking brutalist form of Dallas City Hall is polarizing. The style — which takes its name from the French word for concrete, not because of its appearance — has lately come under fire from the administration of President Donald Trump, which has effectively mandated traditional and classical architecture be the default style of federal buildings. While City Hall may not be your favorite flavor of architecture, it is absolutely a masterwork, thoughtfully designed and immaculately constructed under the direction of I.M. Pei, one of the most significant figures in postwar American architecture. After visiting the building before its official opening in 1978, Ada Louise Huxtable, the dean of American architecture critics, extolled its “breathtaking” spaces, calling it a “major work of architecture and urban design.”

Its destruction would arguably represent the most egregious demolition of an American public building since New York’s Penn Station was torn down in the 1960s, an act of philistinism that essentially launched the modern preservation movement. Losing the building would also represent perhaps the biggest stain on the city’s reputation since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. This would be grimly ironic given that the building was a key component of Mayor J. Erik Jonsson’s efforts to reshape Dallas in the wake of that tragedy.

Within the architecture community, there is broad opposition to any effort to demolish the building. “Preservation Dallas believes that Dallas City Hall should be repaired — not replaced,” reads a statement from the organization. “This is an opportunity for Dallas to show that the people’s building — our City Hall — can be continually cared for and not abandoned. Because if City Hall is up for real estate grabs, are any of our city structures really safe?” The American Institute of Architects is also in opposition. “City Hall should not be demolished,” says Zaida Basora, the executive director of the AIA’s Dallas chapter.

It is unclear whether the city can legally move forward with such a project, at least in the near term. In March, the city’s landmark commission unanimously voted to begin the designation process for the building, a move that places a two-year moratorium on any alteration to the structure without the commission’s approval. Any attempt to circumvent that moratorium would presumably be subject to expensive litigation from preservation and citizen groups.

Members of the Dallas City Council (seated) look on as Mayor Erik Jonsson and architect I. M. Pei (standing, third and fourth from left) present a model of Dallas City Hall in April 1969.

1969 File Photo / Staff

False narratives

Throughout its life, the building has been dogged by misperceptions that feed critics and exacerbate its real flaws. Chief among these contentions is that its tilted concrete facade was intended as a representation of overwhelming governmental authority. It was just the opposite. The smaller footprint of the base was intended to draw visitors into the building and its soaring atrium, and to not immediately overwhelm them with an intimidating and confusing warren of offices and officials.

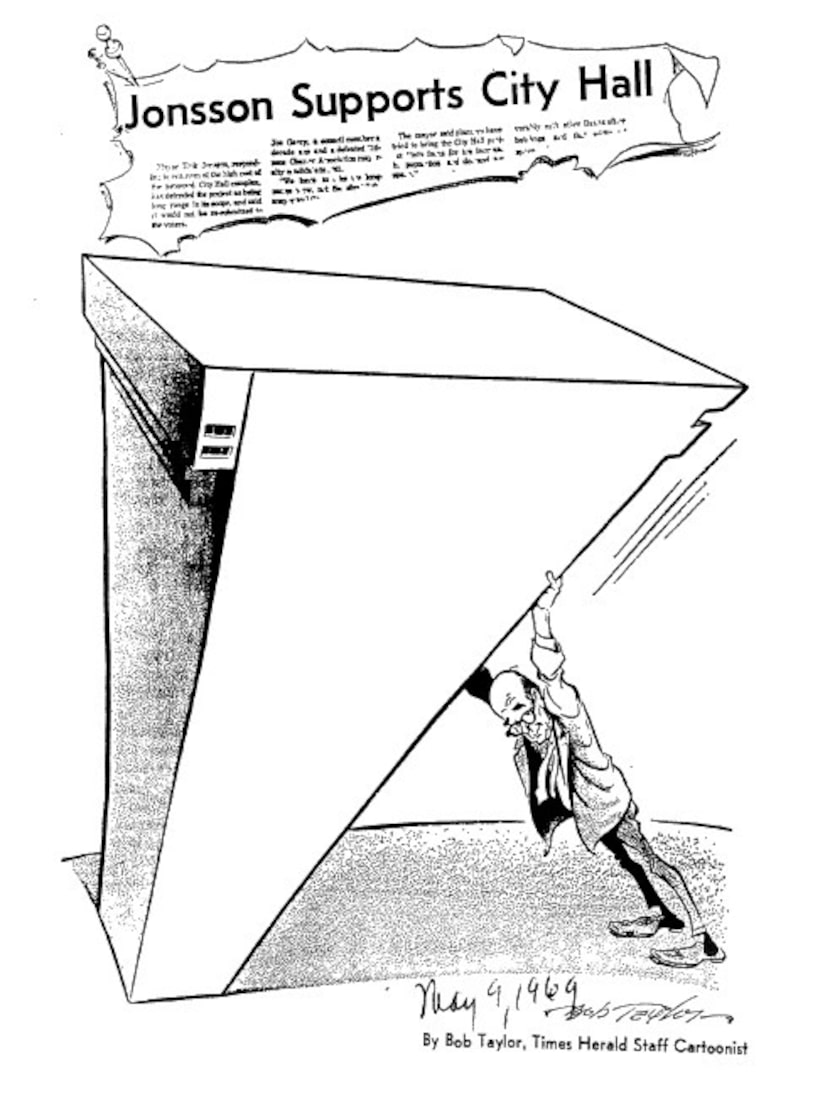

A Dallas Times Herald cartoon by Bob Taylor parodies Mayor Erik Jonsson’s support of Dallas City Hall. Courtesy Dallas Municipal Archives

Dallas Muncipal Archive / Dallas Muncipal Archive

Its open plan was meant to foster cooperation and to literally and figuratively reveal the process of government to the public. “It was a great joy to work in this building, to experience its drama and spatial delights, its materiality, its elegance and its quiet solitude,” says Winters, who worked there for nearly 30 years.

Another misperception offered as an excuse to replace the building is the belief that Pei only added the pylons that front the building because Erik Jonsson worried its slanted front made it look like it was going to fall over. If the building is a compromise, according to this logic, it is not worth saving. But this is almost certainly an urban legend, probably spawned by a series of editorial cartoons by the Dallas Times Herald’s Bob Taylor that showed Jonsson physically holding up the building for which he was the leading proponent.

In every known drawing and model of the project, the pylons are present and essential to the logic of the building, providing visual stability (they are not load-bearing) and a means of emergency egress (they contain the building’s fire stairs). Even if the pylons were an early intervention prompted by Jonsson, it would hardly be damning; architects should collaborate with clients during the design process, and the result here is successful on aesthetic and functional levels.

An exterior view of Dallas City Hall.

Tom Fox / Staff Photographer

An opportunity

Beyond years of neglect, Dallas City Hall is plagued by a bureaucratic growth that has stuffed its halls beyond their intended capacity, taxing its design and its mechanical systems. That misuse is not a justification for demolition. Moving some departments off-site would be far more economical than commissioning a new building, especially at a time when vacancy rates in the downtown core are alarmingly low. Using some of that space for city workers would inject welcome life into the area while relieving the burden on City Hall.

Alternatively, the city could build an annex on the area directly behind City Hall, space now occupied by surface parking that Pei intended as a place for expansion.

In undertaking an overhaul of the building, Dallas can look to the example of Boston, which recently completed a restoration of its own brutalist City Hall, and then designated it as a city landmark. Part of that work entailed the redesign of the barren plaza fronting that building, introducing more landscaping and an elaborate playground for kids. Dallas should consider a similar project, as Pei’s 4.7-acre plaza has never been a success, failing to activate the surrounding area or become a vibrant gathering space in its own right.

Bringing City Hall up to an acceptable condition for those who work and visit the building will be expensive, but it is the only option that respects the city’s heritage while being responsible with the civic purse. The city, it should be noted, had no problem spending $140 million to restore the Cotton Bowl, a building that essentially hosts one marquee event per year.

City Hall was conceived to represent Dallas at its best. It is bold, forward-looking, ambitious, generous and optimistic. In the evening, when the warm Texas sun sweeps across its front façade, it achieves a beauty that is close to the sublime. Destroying it would be an unforgivable act of self-harm.

Dallas, we need to consider tearing down City Hall

Dallas, we need to consider tearing down City Hall

It’s not about the building; it’s about downtown.

Klyde Warren Park to be featured on ‘How Did They Build That?’

The Smithsonian Channel series will examine how Dallas’ urban oasis came to life.