Walk downtown in August and Houston answers in concrete. Heat presses like ballast; cicadas plane the air to a metallic edge; live oaks brace under a sky that refuses to dim. Then the brutalist masses step in — recess within recess, storm-rounded corners, pockets of shadow where temperature drops and the diaphragm resets. Other cities parade doctrine, Euclidean virtue poured in gray. Houston treats brutalism as weather. Concrete sweats, feathers green after rain, chalks white after sun. Facades read like syllabi — semesters of climate written in stains.

Béton brut first named a surface — board grain, tie-holes — before it suggested an ethic. Alison and Peter Smithson’s “as found” accepted grit as information. Reyner Banham cast environment as co-author: building and air in duet, not tableau. Louis Kahn thickened thresholds so doors kept time. Kenneth Frampton gathered the impulse as “critical regionalism,” asking architecture to answer climate, light, and ground rather than chase placeless image.

Houston entered during the petro-boom, under the empire of air-conditioning. Universities grew; courts multiplied; theaters announced intent; concrete replied with gravity. The Gulf revised every line. Thermal cycles widened fissures; humidity inscribed emerald glyphs; hurricanes leaned into thresholds and trained gutters for emergency. Monument drifted toward membrane — thick, rough, porous — tuned to the interval between image and use, body and heat.

That drift reads as survival, not style. In a city where heat kills, storms redraw coastlines, and booms vanish midsentence, adaptable buildings outlast declarative ones. Houston’s brutalism demonstrates rather than declares: stains that map a storm, patches that confess care, an overhang that saves a passerby at three. Value gathers in behavior, not silhouette — mass that damps the thermal pulse, shade that scripts congregation, thickness that practices civic care.

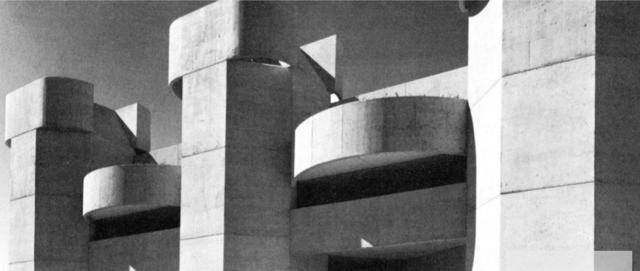

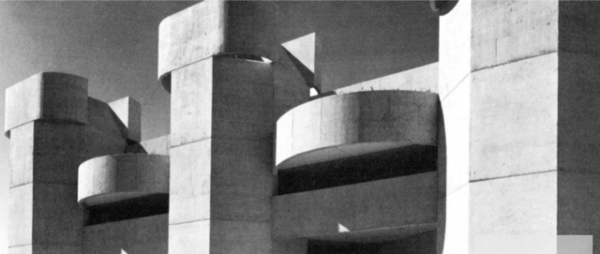

Alley Theatre

Consider the Alley Theatre, a 1960s citadel moored in glare. Curving bastions translate theater-in-the-round into urban mass; glazing retreats from the sun like a stagehand dimming cues. Board-formed grain runs the skin; small tie-holes tick time down the surface. Step into a recess in August and the body knows before the mind: pulse lowers, vision softens. Eighteen inches of wall in places delay the heat wave by hours; the interior stays cool while the facade bakes. Evening reverses the affect — lantern glow pooled behind stone, warmth bleeding to the night. After rain the grain wakes and glistens, each strake a shallow river. The Alley states a quiet thesis: bulk serves climate; mass performs coolth.

MD Anderson Library at the University of Houston

The MD Anderson Library at the University of Houston holds a slower beat. Cantilevers invite bodies during a noon cloudburst; the undercroft keeps a tempered pool of air where attention returns. In the 1990s a vapor barrier slid behind the concrete skin; HVAC retuned for 80% humidity without desiccation. Staff still walk the envelope each quarter, logging where sealants fatigue — a live diagram of The Gulf’s handwriting. Each intervention adds a stratum to the ledger. Banham’s duet lands here as practice, not dream: heavy envelope, careful systems, and the civic rituals shade permits.

Harris County Family Law Center

Ambivalence sharpens at the Harris County Family Law Center. The complex scripts different publics by the hour. At 10, terraces shelter activists; concrete throws voices back with a clean return while overhangs spare skin. At 2, the same terraces thin to a single figure waiting; geometry that protected at morning reads like surveillance by afternoon. At 5, office workers cut through to the rail; the building becomes infrastructure again — one more link in the city’s shade network. Same concrete; three publics. Social media trims the swing from “heroic rawness” to meme, but the maintenance ledger holds the slower truth. “East corner pools every storm,” Maria from facilities says, tracing a rust tear below a frame — water past the gasket, corrosion underway, patch queued for next month. In her register the building doesn’t posture as monument; it lives as patient on a schedule. Maintenance behaves like culture.

Rachel Whiteread, “House,” 1993. © Rachel Whiteread. Courtesy of Artangel

Artists here and elsewhere keep reading that culture, translating building behavior into public sense. For the unfamiliar: Cyprien Gaillard — the Paris-born artist of ruins and regeneration — films the metabolism of concrete: implosions, dust, the choreography of mass and air, turning demolition into a study of time. Rachel Whiteread, known for casting the negative spaces of rooms and stairs, treats void as archive and cooled memory. Gordon Matta-Clark, the 1970s architect-artist who sliced buildings open, exposed how air and light perform long before “adaptive reuse” had policy teeth. In Houston, David Politzer compresses decades of weathering into minutes, letting stains caption the facade. Conservation artist Jorge Otero-Pailos peels pollution from monuments onto latex skins so grime reads as record, not defect. Different methods, same claim: concrete works as a social organ — it cools, gathers, remembers.

An aerial photograph of the Astrodome

Then the Astrodome — infrastructural epic, citywide muscle memory. The ramps still choreograph procession even dormant: spirals that wind speed into ceremony, concrete curls broad enough to swallow a brass band. Game days recede, but the liturgy lingers — radios leaking from windows, forearms on warm parapets, the curve pulling ear and eye toward an invisible field. Those ramps never only moved bodies; they staged anticipation. Tours and pop-ups keep the score alive. Proposals loop — convention center, hotel, park — because the structure still organizes imagination. That counts as use. Artists who stage repair and ritual know this terrain; Theaster Gates builds civic theater out of upkeep, Oscar Tuazon puts plumbing and ductwork at center stage, Monika Sosnowska torques modernist fragments until their behavioral scripts show. Mass, maintenance, memory — one system.

SESC Pompéia

Widen the frame and Houston speaks with other humid modernities through behavior, not silhouette. Quick introductions for the less familiar: Lina Bo Bardi — Italian-born, Brazilian by work — shaped São Paulo’s SESC Pompéia as a pedestrian city of towers and bridges where shade convenes public life. João Vilanova Artigas — a central Brazilian modernist — built FAU-USP, an architecture school that breathes through ramps and skylit seams, pedagogy written as air. Teodoro González de León — Mexico City’s poet of mass — carved foyers like canyons; daylight falls in ribbons, crowds cool by lingering. Their kinship with Houston sits in thick edges and generous penumbra, in rooms that temper bodies before programs begin. This is where Frampton’s regionalism earns its keep: not folklore as garnish, but a demand that structure converse with heat, light, water, and ritual. Read that way, Houston’s concrete speaks Gulf vernacular — shade-forward, storm-literate, stubborn about civic comfort, intent on making weather hospitable.

Local critique often favors smoothness — skyline glass, highway braids, megaproject gloss. Brutalism answers with weight, drag, honest difficulty. In a hot, flat city, difficulty gets indicted as a design crime. Yet difficulty keeps time with reality. When a storm lifts off The Gulf, cities need depth: overhangs that shed horizontal rain; thresholds that drain rather than pool; stairs that dry within an hour; envelopes that buffer a 20-degree swing. Photogenic shells rehearse transparency; Houston requires opacity and density. The best concrete here anticipated that requirement decades ago — before “resilience” became a hashtag, before embodied carbon entered policy — and still offers a shelf of techniques ready for reuse.

No canon welcomes every artifact. Some buildings sealed interiors until air quality sagged; some leaned on fortress rhetoric when programs needed porosity; some turned away from the street exactly when the city wanted embrace. Even so, solutions start with operations. Recut the ground floor; notch shade into the edge; open a wall to indirect light; thicken the roofline; plant as microclimate instrument. These moves match the best contemporary practices — small, exact calibrations that change how bodies meet heat and time. Demolition by fashion forfeits a repertoire adapted — awkwardly at moments, brilliantly at others — to the weather that will script Houston’s next century.

Public sentiment swirls. The account that mocks a courthouse as sci-fi ruin swoons an hour later for its 5-o’clock shadow bands. The critic who decries “ugly concrete” eats lunch under a reveal because the air there actually moves. Houston’s test doesn’t ask for love of brutalism as style; it asks for recognition of practical poetry. These buildings bend light, store coolth, cut out rests in a climate that erases rest. Architecture never ends with images; it scripts bodies and heat and time. On that stage, concrete still speaks one of Houston’s most serviceable languages — and art, at its best here, translates.

Houston’s brutalism never froze. It weathered, cracked, got patched, weathered again — a loop that reads as method once mourning gives way to attention. Weather writes on concrete; concrete instructs the city; the city either learns or demolishes; learning yields adaptation; the building meets the next storm and the next. The loop holds.

Step back into August. Sun presses; air shimmers. The concrete reads differently now — not doctrine imported from elsewhere, but Gulf vernacular written in local weather. The deep shadow at the Alley’s entry argues. The MD Anderson cantilever shelters. The Family Law terraces negotiate. Cross from glare to shade; let the building work; feel breath settle. Stand in the Alley’s pocket, the library’s undercroft, the court’s wind-shielded ledge, and hear what the concrete keeps repeating: mediation over monument. Protesters choose deep steps because voice carries; workers drift under overhangs because the sun insists; students claim cool ledges because attention returns there. Theory names the performance. Artists show it. Houstonians call it Wednesday.