Carolyn Boyd examines the painting sequence of a Pecos River style figure at Fate Bell Shelter in Seminole Canyon State Park and Historic Site. Credit: TXST/Shumla

Carolyn Boyd examines the painting sequence of a Pecos River style figure at Fate Bell Shelter in Seminole Canyon State Park and Historic Site. Credit: TXST/Shumla

Researchers in Texas have uncovered ancient murals hidden in the limestone shelters of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Painted in ochre, black, and yellow, the human and animal figures reveal a visual tradition that endured for thousands of years.

A new study published in Science Advances has now revealed just how deep that time runs. Using advanced radiocarbon dating on organic residues within the paint, archaeologists Carolyn Boyd, Karen Steelman, and Phil Dering have traced the origins of these Pecos River–style murals to nearly 6,000 years ago.

“Frankly, we were stunned to discover that the murals remained in production for over 4,000 years and that the rule-bound painting sequence persisted throughout that period as well,” Boyd, an anthropologist at Texas State University, told Live Science.

Like a Visual Manuscript

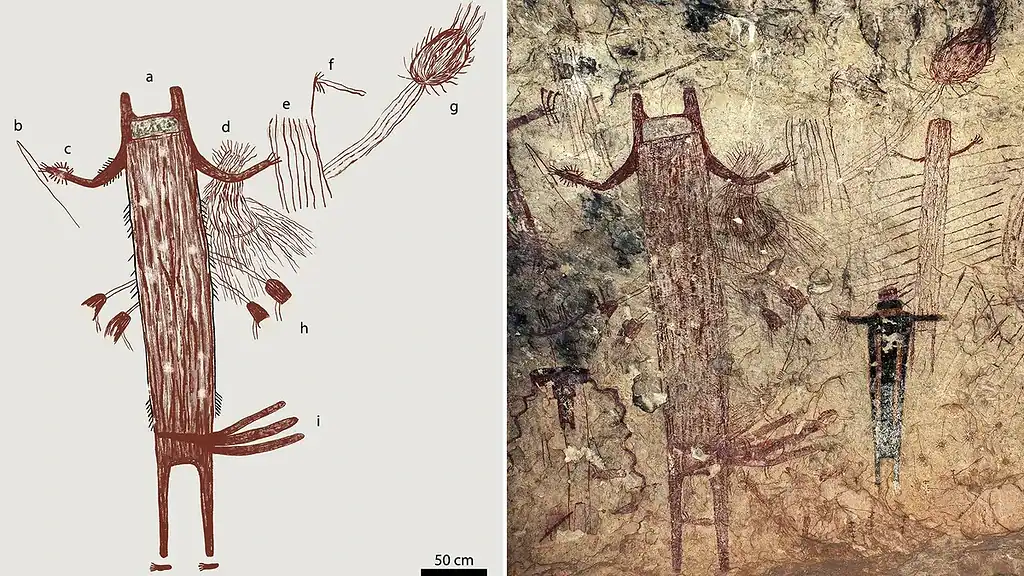

An example of Pecos River-style artworks depicting a human-like figure holding a black spear thrower, with a dart in one hand and red darts and a staff in the other hand. Credit: Courtesy of Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center.

An example of Pecos River-style artworks depicting a human-like figure holding a black spear thrower, with a dart in one hand and red darts and a staff in the other hand. Credit: Courtesy of Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center.

The Pecos River style stretches across roughly 8,000 square kilometers of canyon country in southwestern Texas and northern Mexico. “Many of the 200-plus murals in the region are huge; some span over 100 feet long (30 meters) and 20 feet tall (6 meters) and contain hundreds of skillfully painted images,” Boyd said.

To the nomadic hunter-gatherers who made them, these were acts of cosmology meant to explain the world around them. “They were highly skilled problem solvers with a sophisticated cosmology and a robust iconographic system to communicate that cosmology,” Boyd added.

The new study combined 57 direct radiocarbon dates and 25 indirect mineral accretion dates from 12 mural sites. Their Bayesian modeling places the beginning of the Pecos River style between 5,760 and 5,385 years ago and its probable end between 1,370 and 1,035 years ago.

Using a digital microscope, the researchers found that the artists applied colors in a fixed sequence. The overlapping layers show that the painters worked methodically, building each mural in a planned, consistent way. Therefore, this method meant that a single mural could function like a “visual manuscript,” as the authors call it, created during a single painting event rather than gradually over centuries.

This photomicrograph, taken at Halo Shelter, shows the yellow over red over black paint layers. The black was applied first, then the red, then the yellow. Credit: TXST/Shumla

This photomicrograph, taken at Halo Shelter, shows the yellow over red over black paint layers. The black was applied first, then the red, then the yellow. Credit: TXST/Shumla

Ancestral Deities

One of the most striking aspects of the research is the continuity it reveals. Despite the passage of 175 generations, the artists followed the same rules of paint sequencing, composition, and iconography.

The motifs—human-like figures with spears or staffs, animal hybrids, and recurring “power bundles” extending from the figures’ arms—remained constant even as climate, tools, and lifeways changed.

The study identifies the Lower Pecos Canyonlands as a sacred place where people repeatedly returned to perform rituals. From an Indigenous perspective, the murals were and remain alive. “The murals are viewed by Indigenous people today as living, breathing, sentient ancestral deities who are still engaged in creation and the maintenance of the cosmos,” Boyd said.

More characteristic designs of the Pecos River-style tradition, examples of which are found across the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Credit: Science Advances/Carolyn E. Boyd

More characteristic designs of the Pecos River-style tradition, examples of which are found across the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Credit: Science Advances/Carolyn E. Boyd

The Desert Archive

The Lower Pecos landscape has preserved this library almost by accident. The dry, stable climate sealed pigments against limestone walls, protecting the organic binders that made radiocarbon dating possible.

Each site offers a frozen moment of ritual action. At 41VV584, one of the oldest murals, dated to roughly 5,400 years ago, an anthropomorphic figure with a “power bundle” stretches across the wall. However, at site 41VV1230, one of the youngest, similar motifs reappear, unchanged in form or meaning, despite a 4,000-year gap.

Pecos River style artists incorporated natural features in the rock wall to serve as the eyes and nose of this human-like figure. Like several figures at Halo Shelter, this one has a halo-like headdress and fine lines running vertically down its forehead. Credit: Texas State University.

Pecos River style artists incorporated natural features in the rock wall to serve as the eyes and nose of this human-like figure. Like several figures at Halo Shelter, this one has a halo-like headdress and fine lines running vertically down its forehead. Credit: Texas State University.

The study’s authors see this endurance as evidence of an Archaic cosmovision that outlasted shifts in economy, climate, and population. The murals’ stability, they argue, “ensured fidelity in the transmission of this sophisticated metaphysics” across millennia.

“Perhaps the most exciting thing of all,” Boyd said, “is that today Indigenous communities in the U.S. and Mexico can relate the stories communicated through the imagery to their own cosmologies, demonstrating the antiquity and persistence of a pan–New World belief system that is at least 6,000 years old.”

Ancient Library

“Living Deity.” Credit: Science Advances

“Living Deity.” Credit: Science Advances

After decades documenting the murals, Boyd sees the new chronology as proof that the paintings continued an unbroken, cosmos-centered tradition.

“[The canyonlands are] like an ancient library containing hundreds of books authored by 175 generations of painters,” she said. “The stories they tell are still being told today.”

That continuity challenges assumptions about hunter-gatherer life as simple or static. The Pecos River artists, the study shows, were also intellectuals. These people visually encoded complex metaphysics and passed them on through time as faithfully as any written tradition.