Kevin Lamont Ealy Jr. is no stranger to police encounters at the airport.

The Dallas man had cash taken from his bags at least three times at DFW International Airport within a 14-month period while waiting to board flights, federal court records show.

The first time, in August 2021, federal task force officers smelled marijuana coming from his two suitcases. They searched the cases and found “green leafy flakes,” a dryer sheet and $14,939 in cash. They seized the cash and Ealy continued on his flight to Los Angeles.

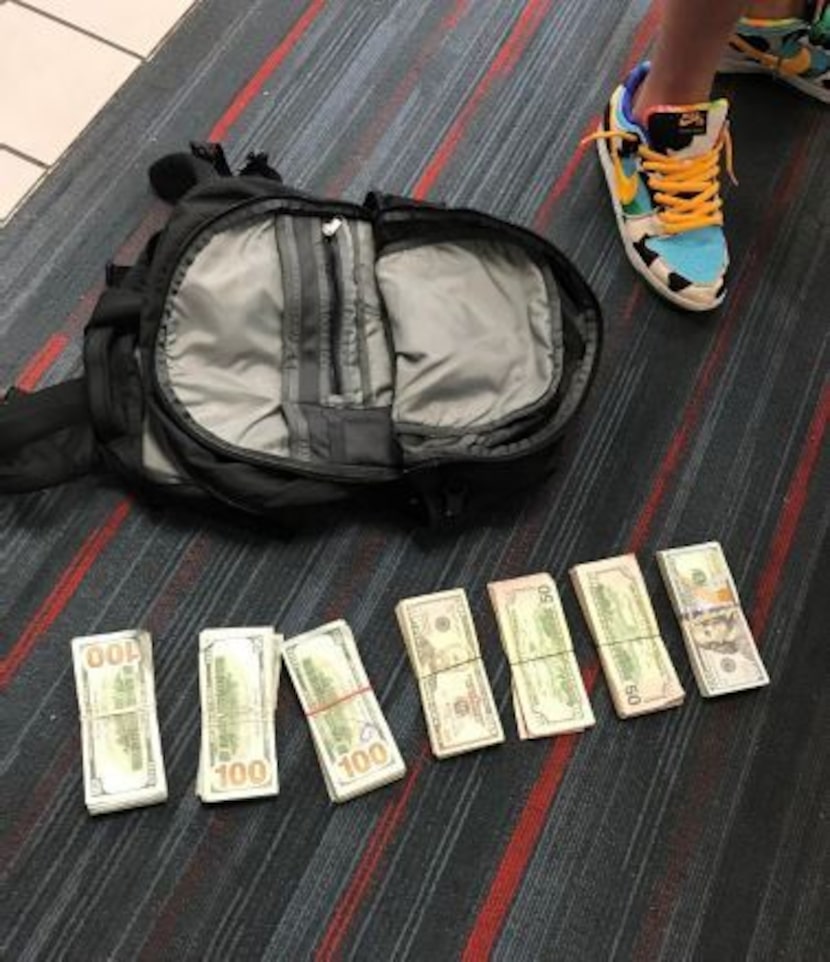

The second time, in July 2022, a police dog again alerted to Ealy’s two suitcases at the airport. Ealy was asked to leave the plane and questioned by task force officers, who asked to search his carry-on backpack. Ealy consented and officers found $19,985 in cash. Again, they seized the cash, and Ealy was free to go.

The third time, in October 2022, officers pulled Ealy out of line on the jetway ramp for questioning and asked to search his backpack after a police dog sniffed it. Ealy again consented and officers found $25,000. Once more, they seized the cash. And once more Ealy was not arrested.

Crime in The News

Such encounters where cash is seized but no arrest is made are not uncommon at airports in Texas and across the U.S. They are effective — at least in terms of collecting cash — because those in the drug trade frequently use commercial airlines to transport drug money.

Effective and, to some, troubling.

Civil libertarians argue that passenger searches at airport terminal gates and jetways lack proper controls to prevent racial profiling and seizures from innocent travelers. They also express concern that law enforcement has a financial incentive to seize money, a concern often referred to as profits over policing.

The Institute for Justice, a Virginia nonprofit, has called it “jetway robbery.” The organization filed a class-action lawsuit against the Drug Enforcement Administration in 2020 on behalf of multiple passengers who had money taken from them. The Institute says innocent passengers were “bullied” into allowing DEA agents to search their bags. Passengers risked missing their flights if they refused to consent to a search.

The airport cash seizures have become a lucrative enterprise for the government. Its exact prevalence, however, is unclear. The government doesn’t keep detailed statistics, except for reporting aggregate numbers for all types of asset forfeiture. The DEA, for example, reported more than 10,000 seizures in 2022 for a total value of $458 million.

Federal agents display suspected drug money seized from a North Texas airline passenger.

U.S. Department of Justice

The most recent detailed analysis of airport seizures appears to be a 2020 report from the Institute for Justice. For its report, titled “Jetway Robbery,” the nonprofit obtained and analyzed data from the U.S. Treasury Department’s forfeiture database and found that $58 million in cash was seized at DFW Airport from 2000 to 2016. It also found that in 90% of all U.S. cash seizures during that time no arrest was made.

The Dallas Morning News analyzed recent Dallas County court records and found that when airline passengers are caught with actual marijuana or other drugs in their suitcases, police typically do make arrests.

But in many instances, there are no drugs. Just cash.

Airport cash seizures are documented in civil forfeiture filings in federal court. Owners can seek to have their money returned by filing a claim with the government. But that is not a common occurrence, attorneys say.

Dallas defense lawyer Arnold Spencer said most of his civil asset forfeiture cases are settled, although some do go to trial. At trial, the government must prove its case by a preponderance of the evidence like in any civil trial, he said.

Amid criticism, the DEA earlier this year ended its practice of confronting airline passengers at terminal gates and asking for consent to search their belongings. But agents with Homeland Security Investigations and Customs and Border Protection, as well as police officers assigned to their task forces, continue to use narcotics dogs to perform “open-air sniffs” of bags and other luggage in airport terminals.

Such searches have been conducted throughout the year at DFW Airport and Love Field, according to federal court records. And just like with the DEA tactic, agents often seize money from suspects without charging them with a crime, court records show.

A positive alert from a drug-sniffing dog gives officers the legal basis to search a passenger’s bags. Police use the dogs to search both carry-on bags and checked luggage. They also typically ask to search the traveler’s mobile phone to look for evidence of drug trafficking or money laundering.

North Texas federal agents as of late have been approaching customers of JSX, a public charter jet operator headquartered in Dallas that offers service at Love Field. JSX operates small aircraft out of a private terminal that’s separate from the main concourses, allowing customers to skip long security lines.

One of the largest seizures so far this year – if not the largest – was more than $800,000 in cash taken in January from a JSX passenger at Love Field.

Homeland Security agents said they could smell marijuana coming from two suitcases belonging to Maxwell Schlesinger, who was traveling to California. A search of the suitcases revealed they contained only U.S. currency, according to court records.

Federal agents seized cash from an alleged California marijuana dealer at DFW International Airport in October 2021.

Krause, Kevin

Schlesinger is contesting the civil forfeiture in court. He has not been charged with a crime in federal court in North Texas. Spencer, who is representing him, declined to comment on the active case.

In February, Johnny Guzman expressed surprise when drug dogs searched his bags at JSX.

“You have canines here?” he said to officers who approached him.

Indeed, the dogs had alerted to his baggage. Task force officers seized $356,880 in cash from his suitcases, records show. Guzman was not charged with a crime in connection with the case. The government settled the forfeiture case and $178,440 was returned to him.

Frequent flyer

Ealy, 32, did not file any claims to have his money returned, and default judgments were entered in each of the three civil forfeiture cases, court records show.

Prosecutors said Ealy “appeared to be traveling from Texas to California to purchase and ship marijuana back to Texas to sell.” At the time, Ealy was on probation for previous drug offenses out of Dallas and Collin counties, prosecutors said.

While Ealy was allowed to walk away at least three times after his money was seized at DFW airport, the DEA had – unbeknownst to him – opened a criminal investigation on him after the third airport encounter.

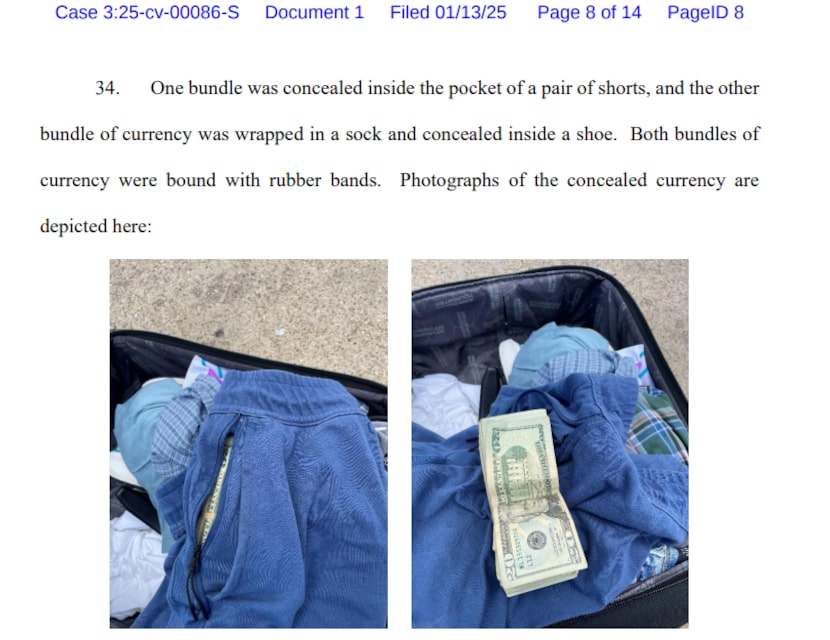

Related

Ealy was arrested in Oklahoma in January 2023.

Ealy was a passenger in a car that was pulled over on Interstate 35 just north of the Texas border, court records show. The Dallas rapper was charged with possession of drug proceeds — $28,000 stuffed into a backpack in the backseat, court records show. Ealy admitted he was going to use the cash to buy marijuana in Oklahoma that he intended to sell in the Dallas area, court records show. The disposition of that case is unclear.

Then, U.S. Marshals showed up at Ealy’s house in July 2023 with an arrest warrant. They found at least 7 pounds of marijuana in the Dallas house along with $4,780 in cash, expensive jewelry and a semi-automatic rifle, court records show.

Ealy pleaded guilty in federal court in Dallas to interstate travel or transportation in aid of racketeering enterprises and agreed to forfeit the cash and jewelry, records show. He was sentenced in 2024 to two years in federal prison. He was released from federal custody in November, prison records show. He could not be reached for comment.

Marijuana sales are legal in most states, whether for recreational or medical use, or both, including in Oklahoma and California. But not in Texas. And not in the federal criminal system.

Attempts to reach Ealy’s attorney by phone and email were unsuccessful.

Ealy was a prolific air traveler, according to court records. Prosecutors said he traveled more than 40 times in 2020 alone from DFW to Los Angeles International Airport.

In at least one instance, court records show, Ealy flew first class. He also was a member of American Airlines’ customer loyalty program, court records said.

Suitcases of money

Like Ealy, many of the passengers whose cash was seized in North Texas terminals had booked one-way flights to Los Angeles.

Drug traffickers use the commercial airlines to transport drug money to keep it “off the books” and “outside the banking system” that is monitored by authorities, said Assistant U.S. Attorney John Penn in a January court filing.

Federal agents tend to target passengers based on a few factors: those with criminal records; those who bought tickets within 48 hours of their flights; and those traveling to big cities where marijuana is legal and abundant, such as Los Angeles.

Just as agents have a strategy to detect would-be targets, those in the drug trade have a strategy to avoid detection.

To try to mask the pungent odor of marijuana, many drug traffickers line their bags with sanitizing wipes or clothes dryer sheets, or they will spray the interior with perfume or cologne, court records show.

In reports, agents cited circumstantial evidence such as a traveler’s criminal record, their inconsistent or changing stories when questioned, their display of nervousness, and a lack of clothing and personal items in their bags.

North Texas federal court records detail a 2024 cash seizure at DFW Airport.

U.S. Department of Justice

A search of travelers’ phones often turned up damaging evidence, including text messages discussing drug deals and photos of drugs, according to court records.

When asked why they had so much cash, passengers offered a variety of reasons, such as legitimate business dealings or an intent to purchase vehicles or real estate.

In some of the cases, the government agreed to a civil settlement in which the owner was able to keep a portion of the seized money, court records show.

Many travelers don’t file claims or otherwise contest the money seizures in court for good reasons, Spencer said. The cost of a legal defense, he said, is often greater than the value of the money seized. The seized cash, in essence, is a cost of doing business.

Still others, Spencer said, do not contest cash seizures because they fear vindictive prosecution, or they have concerns about possible collateral legal entanglements involving tax or immigration matters.

Constitutional concerns

Civil libertarians have long criticized such law enforcement encounters with airport passengers, saying they often lead to constitutional violations.

The Supreme Court has ruled that motorists should not be made to wait for the arrival of a drug-sniffing dog during traffic stops unless the officer has probable cause that a crime was committed. The Institute for Justice says the same should be true for airline passengers.

Drug-sniffing dogs have a high false positive rate, the Institute says, and are often motivated by a desire to please their handler. Also, most U.S. currency in circulation has trace amounts of drug residue, the nonprofit argues, that could cause a drug dog to alert its handler.

Spencer, a former federal prosecutor, said innocent travelers are being “caught up by this fishing expedition.” It’s impossible to know, for example, why a dog might alert to a bag, he said.

“A strong case can be made that, at best, these dog-sniff alerts are very subjective.”

Dan Alban, an Institute for Justice senior attorney and the co-director of its National Initiative to End Forfeiture Abuse, said drug dogs are “basically just probable-cause machines that alert when their handlers want them to.”

An American Airlines plane is seen at the gates of Terminal D at DFW Airport on Tuesday, Nov. 4, 2025.

Smiley N. Pool / Staff Photographer

He called it questionable to seize cash when a search of luggage based on a drug dog alert does not produce any drugs.

“The dog’s alert was either faulty,” Alban said, “or it was just an alert to the trace amounts of drugs in most cash that has been circulated.”

Federal law does not limit the amount of cash passengers may carry with them on flights. And travelers on domestic flights don’t have to disclose it anywhere.

Simply traveling with a lot of cash, Spencer said, is not sufficient proof of a crime.

In late 2024, the Department of Justice suspended the DEA’s airport operations in response to a report from its watchdog – the inspector general – which expressed concerns about a lack of oversight and controls.

DEA agents were not receiving required training, the report said, nor were they completing required documentation of traveler encounters.

The report said that by operating without “critical controls” such as adequate policies, guidance and training, the DEA was creating “significant operational and legal risks” for the government. Those risks included improper searches violating the rights of innocent travelers; a waste of law enforcement resources; and possible damage to the DOJ’s asset forfeiture and seizure activities, according to the report.

The DEA’s practices also had been subject to growing scrutiny from members of Congress.

The DEA said in January it would no longer conduct consensual searches of travelers and their bags at airport gates and jet bridges, absent an ongoing investigation or valid concern about illegal activity.

One controversial 2024 airport encounter was highlighted by the Institute for Justice and included in the DOJ’s inspector general report.

A passenger was approached by agents while waiting to board his flight, which he ended up missing because the DEA wanted to search his bag. Agents had no reason to suspect the man of drug activity. He had no criminal record. And their dog alerted to his bag despite the fact that their search turned up nothing incriminating.

The passenger recorded the incident with his phone – a video that went viral and sparked outrage.

The bag search was based on a tip from an airline employee acting as a paid DEA informant. The informant had provided the man’s name to agents because he booked the flight within 48 hours of departure. The informant had received “tens of thousands of dollars” from the DEA for information previously provided to agents, resulting in cash seizures, according to the inspector general report.

The case renewed scrutiny over the government’s use of airport informants, some of whom were paid handsomely for their assistance in providing agents with “suspicious travel itineraries,” the inspector general report said.

Suspicious, Spencer reminds, is not always criminal.

“They capture a substantial amount of legitimate proceeds,” he said, “and really challenge the constitutional rights of these individuals who’ve done nothing wrong.”

Related