“We all live stories,” Hyde Park Storytelling co-founder Matthew Stoner says simply. “I love listening to people’s average day, my friends and my family. I love hearing about what they’re doing and all of the drama, or not drama, that ensues.”

All day long, at work and home and everywhere in between, we’re telling true – maybe a little tall – tales, teaching and thrilling each other with our experiences. Our most prized narratives, those with a shock factor, comedic timing, or a lasting personal impact, become serialized chapters in our oral memoirs, doled out to friends and family, lovers and coworkers, as tokens of ourselves. We perform for, and sometimes with, those close to us these defining moments again and again until the delivery itself is a part of the plot.

For the uncountable quantity of anecdotes in each of our autobiographies, it’s statistically rare that they’re shared with total and complete strangers, much less from under a spotlight. On the stepping stone between conversational fodder and the multimillion-dollar memoir industry, there lies another opportunity to spill your somewhat-polished guts: storytelling events.

Varied in approach and audience, these intimate gatherings might owe their popularity to the not-yet-dusty wings of the Moth. The live show-turned-radio series-turned-podcast, started by novelist George Dawes Green in New York City in 1997, sparked a wave of localized live storytelling events in a similar format, taking an Eighties nationwide trend of large storytelling festivals to more accessible stages. Many are familiar with the concept: So-called ordinary people gather to swap narratives centered around a broad theme. At the Moth, and Austin’s own Testify, storytellers write out a script and are coached and practiced when they reach the microphone.

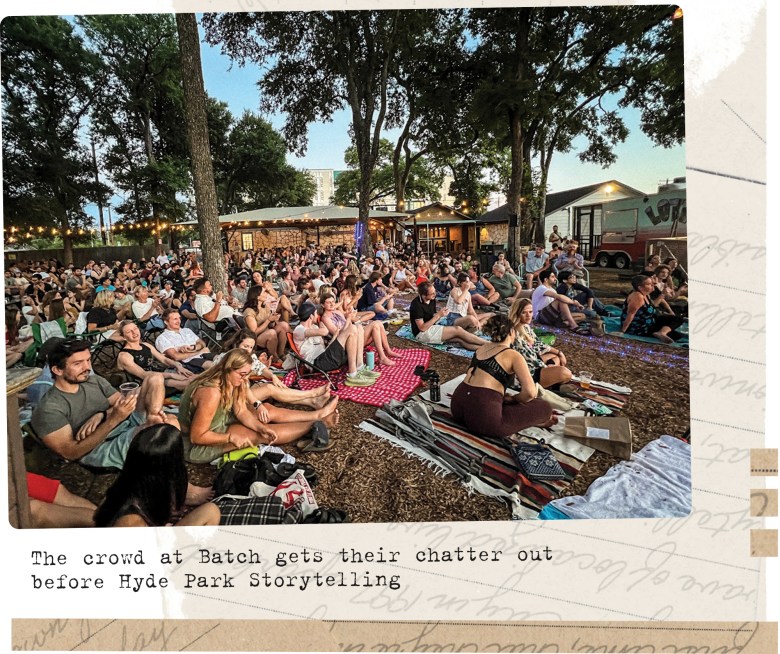

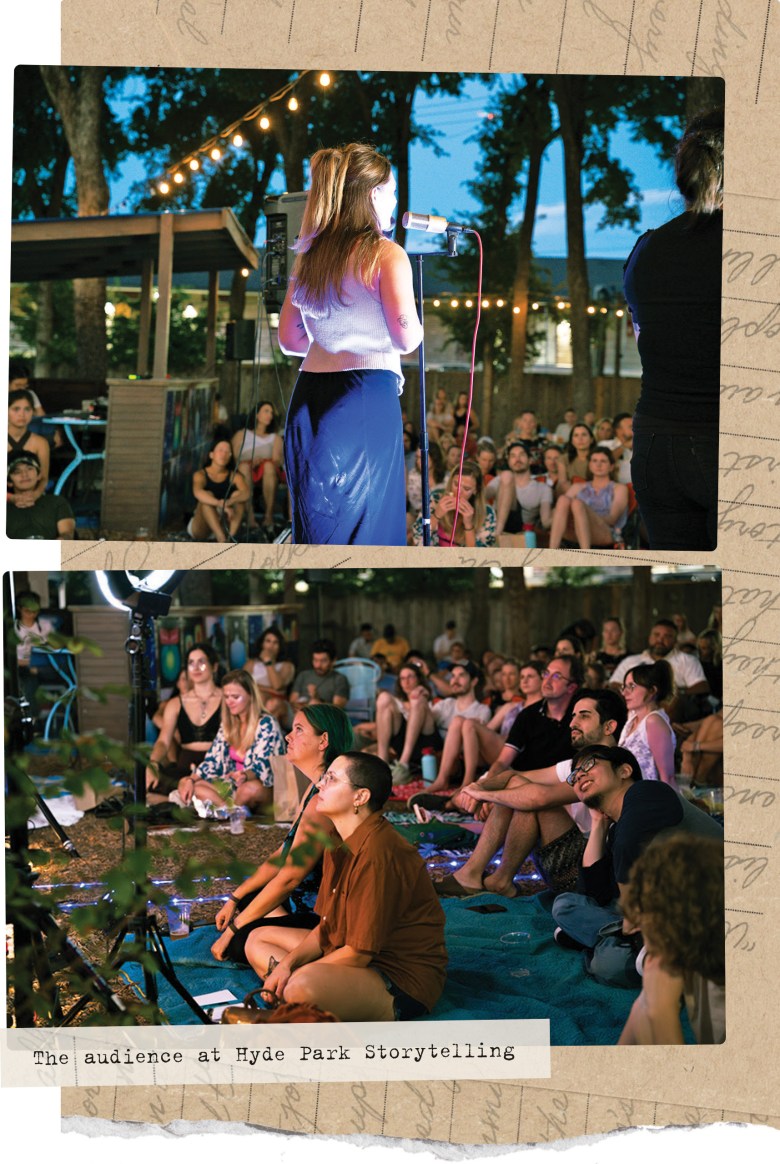

Local series Stories on the Lawn; Greetings, From Queer Mountain; and Hyde Park Storytelling take a more laid-back approach to the same idea. Whether criss-cross applesauce on the Neill-Cochran House lawn, seated beneath neon lights at Cheer Up Charlies, or spread on blankets at Batch, the wide-eyed audiences at these storytelling events are perhaps more rapt and attentive than your friends on their barstools or your family at the dinner table.

“We all want to be heard, seen, listened to,” Stoner says. “We encourage the audience to respond like it’s the best story they’ve ever heard, and part of that is knowing that a lot of our storytellers are telling for the first time, that they’re in front of an audience, sometimes 250, 300 people, and we want like them to feel like a rock star.”

From Back Pocket to Center Stage

Meredith Johnson’s path to the storytelling stage is – you’ll have to forgive me – a tale as old as time.

After watching Hyde Park Storytelling host Stoner perform at ColdTowne Theater, where the two practice comedy, Johnson felt compelled, as so many of us have at one point or another, to approach him afterward and tell him a story of her own – a deeply personal, vulnerable story.

“He asked me: ‘Can you say that in front of 200 people?’” Johnson laughs. “And I said yes.”

Credit: Matthew Stoner

Credit: Matthew Stoner

Yes-men – rather, yes-people – dare friends, bucket list-tickers, writers, comedians, and other attention-seekers (complimentary) to stand on oft-shaky legs in front of microphones month after month, bravely letting strangers into personal moments. Each event has its own niche, its own genre of stories it implores everyday people to tell in a not-so-everyday way: Barrel O’ Fun’s monthly Nerd Nite invites folks to share their passions PowerPoint-style; Half Empty, Half Full summons comedic and literary Austinites to ColdTowne for stories in the form of a pessimist vs. optimist debate.

At Hyde Park Storytelling, the prompt is simple: Tell a true story that happened to you.

“A story in this format doesn’t have to be a breakup, falling in love, a car accident. It can be any small or big moment in your life,” Stoner says. “It’s got to have some impact [on] you. It’s got to change you in some way.”

“It doesn’t have to be a big catastrophic thing,” producer Casie Luong adds, recalling two of her favorite stories told over the event’s 11-year run: one about a rat infestation – which, OK, might be catastrophic to some – and one about a chocoflan that just wouldn’t turn out.

No matter what kind of story you have to tell, or how many times you’ve recited it to your family and friends, sharing a part of yourself with an attentive, expectant audience requires some courage. Even Johnson, who has read her poetry countless times and now also performs as a stand-up comedian, nearly didn’t make it onstage.

“I was incredibly nervous. I was very scared and right before I went on I said, ‘I can’t do it. I’m not gonna do it,’” she says. “It felt very different because when I am reading my poetry, I am expressing my [inner] artist. I am almost – what do they call it – [expressing my] alter ego as art.”

Regaling an audience of over 250 with her tale of accidentally attending a clown class and suffering humiliation after humiliation as she tried and failed to clown around – an afternoon she’d previously described as “the most horrifying, traumatic, embarrassing moment” – became a different kind of story. “It helped me reframe the experience in a much lighter light,” Johnson says. “When we have these painful experiences, they’re so humane, they’re so human. They’re so relatable because we all go through things like that.”

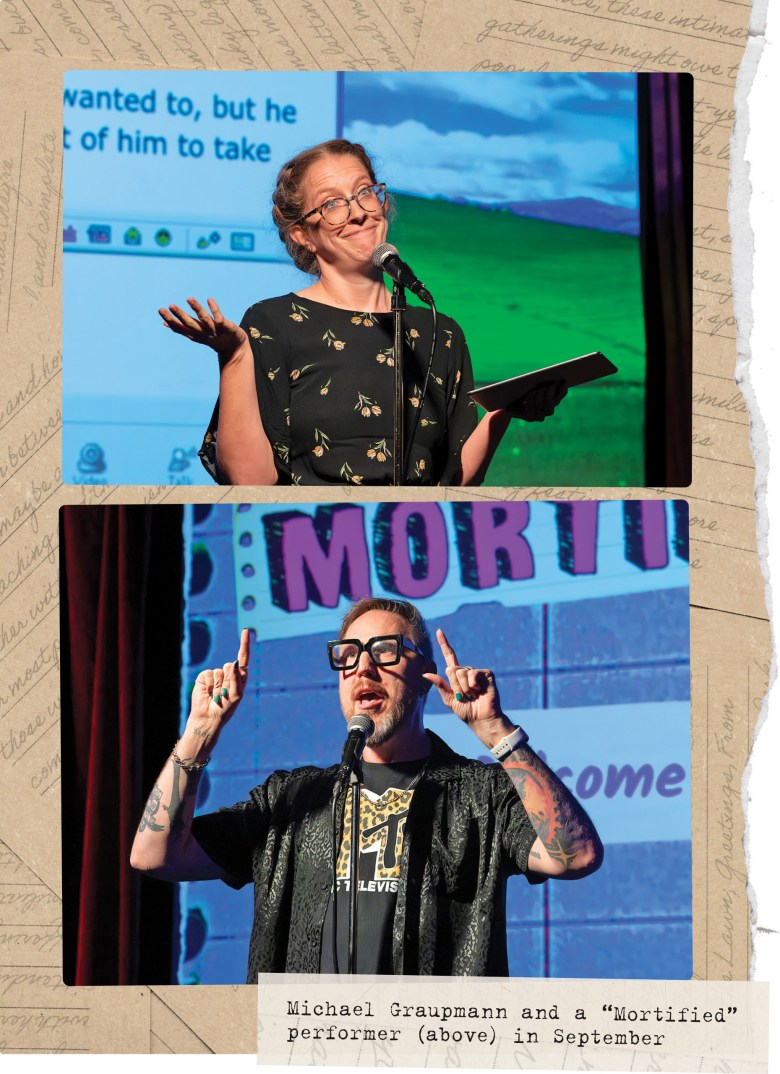

Mortified, a quarterly reading event launched in Los Angeles and now in nine cities including Austin, is premised on that very idea. Highlighted with visual evidence, Mortified draws on embarrassing moments from our youth, inviting adults to read their journals, poems, letters, plays, etc. from childhood and adolescence.

Credit: John Anderson

Credit: John Anderson

In Austin, Michael Graupmann has led the team of Mortified producers, occasionally turned bit-part-players, for 11 years. Taking stories from roundtable conversations to the spotlight is something he specializes in, having trained and worked in speech and debate circles before becoming a veritable storytelling magnate.

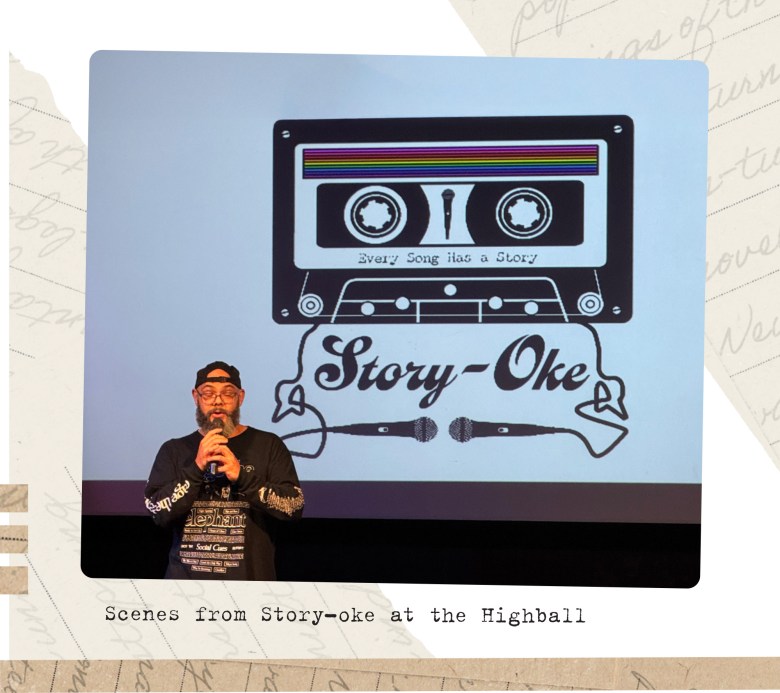

“It puts a magnifying glass on things, and it makes things a little bit more grandiose when you put it on a stage,” they say. Lanky and tatted, often found in long-cut jorts and a black T-shirt, Graupmann’s thick-framed glasses and gregarious smile are familiar features of the storytelling stage. Since 2017, he’s shared the helm of Queer Film Theory with Lesley Clayton, and this year the duo, aided by co-host Megan Kluck, launched a new show, Story-oke, at the Highball.

Queer Film Theory, like Mortified, asks speakers to fashion a tale from preexisting material – this time, from someone else’s pens – and cameras. LGBTQIA “professors” take to the stage once a month to exalt the queer subtext and fanfic-able “friendships” of the straight-presenting movies that impacted them. Over the years, Graupmann and Clayton have seen the QFT community grow and diversify, introducing new films and narratives to the stage.

“I love how brave people have been,” says Graupmann. “We’ve had more trans folks and we’ve had more nonbinary folks opening up and, honestly, folks who identify as bi and pan as well, feel more comfortable saying that in public, and that is different from when we were doing [the show] a while ago.”

At August’s action movie-themed session, Graupmann himself dug into Tom Cruise’s very homoerotic bathroom fight scene alongside Henry Cavill in Mission: Impossible – Fallout; Clayton extolled the queer relationships in F9: The Fast Saga; and cult classic-lover Austin Hambrick walked the audience through the soft-masculine undertones of Hard Boiled’s famous teahouse shoot-out scene.

Hambrick, cool as a cucumber while proclaiming his love for Chow Yun Fat now, was everything but the first time he presented at QFT. As an actor and writer, he didn’t expect the quaky limbs and sweaty palms that greeted him as he walked to the front of the Highball to give his sincere and somber, carefully practiced speech on 1981 slasher Butcher, Baker, Nightmare Maker.

“There’s a weird difference between acting and being a goofball on stage and then speaking to an audience,” Hambrick notes. “I remember my legs were shaking, and I stumbled through it and it was not my best work.” Afterward though, “I got bit by the bug,” he laughs. He’s since performed five or six times and recently extended his onstage résumé to include Story-oke. The show, in which performers discuss a song’s importance to them before taking it away karaoke-style, was a natural fit for Hambrick.

Credit: Courtesy of Story-oke

Credit: Courtesy of Story-oke

“I am an avid karaoke person,” he says. This August, he treated the Story-oke audience to his Broadway-level interpretation of “Wig in a Box” from the musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch. “I try to not be a center of attention in my daily life, and this is the opportunity you have to be the center of attention and all eyes are on you,” Hambrick says jovially. “If I see people laughing or see people smiling, that’s what really drives me.”

All that time soaking in laughter on the Highball stage eventually sparked something more for Hambrick, encouraging him to try out stand-up comedy. When he chatted with the Chronicle, the artist and writer had just bombed for the first time – a rite of passage for all funny people. Never a great feeling, but Hambrick felt able to brush it off thanks to many nights spent sharing an even more vulnerable side of himself.

Ellie DeCaprio, the current host of Greetings, From Queer Mountain, a free-form, format-exploring show, came to storytelling from the opposite direction. “It offered me, as a stand-up comedian, a place to share my authentic voice for the first time, just sharing stories without needing to put it in a punch line every 15 to 30 seconds,” she explains. Greetings, From Queer Mountain was co-started by ex-Austinite comedian Micheal Foulk, also the mind originally behind Queer Film Theory, to gather queer voices in the comedy and literary scene on a hypothetical slope where they could share authentically and safely.

“[That’s] why all of the shows are so important,” Graupmann says with a pained expression, pointing to anti-queer legislation and rhetoric and isolationist trends that arise in response to immigration crackdowns and political violence. “I say this onstage every single time: Things keep getting worse, and I’m feeling really down about it,” they sigh. “I want to give people the opportunity to combat that and to still have moments of joy. To me, nostalgia and community and self-expression are the elements of what get us to that place of joy, and that’s what I want to create as much as possible.”

Ushering Understanding

Creating a welcoming audience, a forgiving and embracing temporary community, starts long before the first performer steps onto the stage or stumbles over their lines. Every element of the production, from the schedule to the stage setup, is considered by these community-driven hosts.

Hyde Park co-producers Stoner and Luong encourage folks to arrive an hour before the show, plenty of time to get the chatter and wiggles out. They adjust the microphone between each performer and announce early on that applause is mandatory and happens the entire time a performer walks to and from the stage. It’s a practice that might seem performative, or overly encouraging, but underlines the point of these events: They’re not crafted to launch careers or personal brands, they’re not highly rehearsed productions, they’re real people telling stories to other real people in real time.

Credit: Majed Joesephi

Credit: Majed Joesephi

“You, as the host, have the responsibility to create the space as an open and welcoming one, [and to] give [the audience] an idea of what they’re in store for. In most of our shows, the hosts start things off by doing an example of it. We refer to that as being the sacrificial lamb to get the audience warmed up,” Graupmann laughs. “It is hard to begin the evening, and so we want to take that [burden] off of our first performers.”

The teams behind these productions often don’t fully know what performers will present – “I like being surprised,” says Stoner – so, based on a few sentences or a movie title clue, they arrange the run of the show around audience catharsis.

“It’s like a song. It’s like a story. It’s the hero’s journey,” Graupmann says with a sweeping gesture. “You’re doing that in the programming for the show as well.”

In the chicken-or-egg ouroboros of human nature, judgment is always nipping at storytelling’s heels. We tell stories to pass judgment on ourselves and others, to elicit advice – a form of judgment – and to convince people of our intentions in order to, perhaps, influence their judgment. Everyone’s a critic, even more so in our age of ubiquitous 5-star ratings and glossily curated social media feeds. You might assume it makes imperfection-embracing audiences hard to come by, but Stoner and Luong see it differently.

“I think that’s the allure of the show,” says Luong. “Everything’s so curated on the Gram. This is real, and it’s messy. Sometimes speakers flub and they freeze up and [say], ‘Oh, I forgot!’ But the crowd’s just like, ‘You got this!’ It’s so forgiving and real in that way. People crave that in a world of curation.”

Greetings, From Queer Mountain host DeCaprio, like all of these moderators, has felt the impact of that forgiveness. “My favorite part of being host of the show is when people perform onstage for the first time in their life because they felt comfortable and safe enough to do so, and even in an unpolished or scared state of being.”

Johnson, unsuccessful clown yet successful storyteller, synthesizes what draws us to the stage, whether we sit in its shadow or climb onto its pedestal.

“I really think that storytelling is the lifeblood of our experience as human beings and that we really [should] hold onto it: the art, the craft,” she says. “It’s really about sharing experiences with others and not isolating. Storytelling is crucial to culture and understanding how we relate to ourselves and others and I’m so grateful to have been given the experience of doing that.”

This article appears in October 17 • 2025.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.